Actions of the Somme Crossings. Men of the 20th British Division and the 22nd French Division in hastily dug rifle pits covering a road, Nesle sector, 25th March 1918.

the Frenchman in the foreground has a Modele 1892 Mosqueton, and the British man behind him has a No1 MkIII* SMLE. The machien gun in the back is a Hotchkiss 1914.

Original Source : IWM – Catalogue number: Q 10809; Colorized by Histoire de Couleurs Facebook Group.

That photograph does show how good British camoflage was during WWI. I did not even notice the British soldier until I read the caption.

It has always surprised me that after the French realised that red trousers were a bad idea in modern warfare, they adopted a horizon blue uniform. Most armies by 1914 had come to the conclusion that you needed to merge with the scenery, not the skyline. As ever, the French had to be that bit different, but I wonder how many men were shot in horizon blue who would not have been in khaki?

You should remember these are not the actual colors. They are an artist’s interpretation. Sure, horizon blue was visble, but this photo shows a world of pastels, which has some problems, i.e.-the French helmet color is far too light for 1918. From all reports, horizon blue when mudded up, which happened rather quickly, blended in about as well as the other uniforms.

I’ve always assumed that brightly colored military uniforms were a kind of cross between a peacock’s vanity and a gorilla’s chest thumping display. It would seem the worst possible decision in the age of firearms, and surprising that it lasted as long as it did on the battlefield. Though it seems that in practice, most of the combatants that employed stealth fighting techniques, such as American Indians, were generally routed by forces that wore bright uniforms and fought from formations resembling a marching band.

You misunderstand the dynamic at work here.

The uniforms were meant to stand out; and not just for use in identification of friendly forces. Instead, the calculation was made that you would gain appreciable psychological effect on your enemy if he were to look out of his position and see the full mass of your forces coming for him. In that mode of thought, camouflaging your troops is what is foolish; you are then masking your strength and sacrificing a key morale effect, which was the key weapon of the Infantry in the era before mass mechanized fires. That effect was “intimidation”, and the French excelled at it–How many of their Napoleonic-war era opponents simply fled, as opposed to standing and fighting, once they witnessed the mass of the French armies coming for them?

War didn’t work the way (and, still doesn’t…) many observers seem to think. You examine uniform choices from that era, and see stupidity. I see a natural conservatism, and a desire to compromise with principles learned to be effective on historical battlefields.

There is a lot more to the issue than what the average modern sees, or understands of it all.

Colorful uniforms go far beyond battlefield function. In all the eras leading up to the 20th Century, the populace was largely made up of the working poor, serfs, and peasants. These people had spent generations dressed in little more than rags and at best had functional work clothing. Fancy, colorful uniforms served many purposes in society.

First, it was an excellent recruiting tool. Issuing uniforms like this were just as powerful as an incentive to serve as was regular (meager) pay and bad food.

Second, it put the lowest private above the masses of the lowest class. Clothing was the chief indicator of social standing, and for the poor rabble, this was a huge step up in the world.

Third, it projected the authority of the monarch/government. Even without weapons, clothing projected power.

Finally, all those elements combined bolstered esprit de corps. In all the previous ages of massed combat, fought largely in the open, a soldier’s willpower to fight was the most important element of success on the battlefield. National pride was everything.

One last bit, you’ll notice that the more elite the soldier the more elaborate the uniform. Many times, even more elaborate than officers. It was critical to motivate the lower classes into national service. Believe it or not, a fancy uniform was a major factor. Fancy uniforms are still an important part of military service.

Good points, clothes themselves where a luxury almost once. Particularly decent ones…

Yes, the Imperial Guard was quite a sight what with the tricolors waving, bayonets glinting, stalwart Grognards shouting war cries and bear skin busby hats… The pantalon rouge and kepi wearing splendor of the offensive a outrance and shock of elan vital was literally shot to pieces in the Battle of the Frontiers. Losses were more horrendous than even the first day of the Somme for the UK’s New Army.

The French had thought of eminently practical modern uniforms in 1912, but it didn’t happen. Horizon bleu did not survive into the 1930s, but the muddy, moutarde brown of the colonial troops did…

Perhaps they were inferior in the cold, but I always thought that Italy had some of the more practical uniforms in WWI, and clearly the UK’s WWII battle dress appears to be an eminently sensible response to the WWI uniforms. Then there were the WWI officers: Ordering French troops to take off British-derived rain coats. Being soaked through is more important than being out of uniform, after all. No blankets in the front line trenches, thank you very much. Musketry has become de-emphasized, oh dear… Well, no hand grenades for the assault then. Be sure to put the cavalry officers over their infantry counterparts, just in case the big push really goes as planned and we’ll need them for the break through… Etc. etc. etc.

While I agree with what you wrote, we must also remember that the colorful uniform was a product of the budding Nationalism of late 17th and early 18th century in Europe. Before that era significant percentage of soldiers on all sides inn Europe were usually mercenaries, and while they may have have had some common recognition signals, they didn’t wear anyone’s national colors. They fought for money and loot, and sometimes from personal allegiance to their captains, but of course also for each other, like most armies throughout ages. Allegiances even in the national armies were felt, if they indeed were felt, more to the person of the monarch or the immediate captain of the army rather than any abstract nation. That is also why monarchs usually led important campaigns themselves.

In the Antiquity at least the Romans had fairly uniform equipment, but we don’t know if they really had uniform color schemes like they do in movies. Shields may have been painted with uniform colors, but possibly only within a legion rather than the whole army.

Yes, I agree RE: nationalism. The scarlet uniforms of Great Britain arose with Cromwell’s New Model Army in the English Civil War in the 17th century. The warrior kings of Sweden thought it a fine idea for the soldiers to wear the colors of the national flag–blue and gold. And so on. There is some evidence that Scottish levies, from highlanders mustered by their laird to the mercenaries and other troops used the salitre of St. Andrew as a sort of “badge” during campaigns against English kings.

Thanks for the info on the Romans. Not my field, certainly. I wonder about some of the hoplite heavy-infantry of the Greek city states in antiquity, and for that matter, the “super phalanx” of Macedon in the Hellenistic era.

Moving to the modern era, I frankly do not see how anybody can distinguish one from the other… Friend from foe, etc.

Headgear tells an important story. From the exaggerated height offered by the shako … to the German pickelhaube with its fearsome-if-also-rather-comical spike … From peaked service caps to the practical but “unsoldierly” “Gore-blimey” winter hat with earflaps … To the steel helmet.

“pickelhaube with its fearsome-if-also-rather-comical spike”

It was use to distinct infantry (spike) from artillery (ball), for artillery pickelhaube see http://www.kaisersbunker.com/pt/artillerie.htm

Thanks/Spacibo Daweo! Of course, the royal Bavarian army did not use a separate artillery ball on the top of the pickelhaube, but just another spike… But yes, the Preußen und so weiter did. Of course, there was still another addition: The “tchapka” for the Ulans or lancers merely replaced the spike or artillerist’s cannon ball!

Of course, as most people know, the U.S. Army and C.S. Army in the, erm, “late unpleasantness” used French-derived Zouave hats, a few tricorn hats early in the war, campaign hats, particularly in the west, but mostly vast numbers of French-derived kepis and the rather strange “bummer” or “forage cap” that looks like the spawn of a kepi and a horse feed-bag. A personal favorite of mine is the New Hampshire infantry’s “whipple-hat” combining the campaign hat and the kepi, albeit with none of their virtues as headgear.

After Germany unified at Versailles in the wake of France’s defeat, the U.S. Army of the 1880s adopted the pickelhaube–albeit in a sort of Victorian variant–as the dress hat!

Yeah, all true in formation fighting of the 17th century, where forces stood and squared off against each other as opposed to digging in and setting up interlocking fields of fire with machine guns. it all ended the moment the machine guns started turning hundreds of thousands of real men into piles of dead meat in ww1.

I was just thinking the term Khaki sounds foreign, perhaps Indian. And it is, which explains the British use of it.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khaki

In the 2nd Boer war our army already wore it, by the time of WW1 perhaps France just hadn’t transitioned so had more things to worry about than new clothes when the war came arpund. Or it was a combination of that and they didn’t want to because they were French and be dammed, or just that.

My understanding–limited though it is–has it that first use of khaki in battle by U.S. forces was during the June 1898 landings in Guantánamo by the USMC. Of course the dress uniform/parade dress was blue. The “tropical uniform” however was khaki. I wonder if khaki may have made an appearance during some of the later Indian Wars, but thus far, I don’t find it…

It was France under threat of… Occupation, presumably. By Germany in WW1. So wearing a “flag” might have been important to them for morale etc, or the Generals thought so. Blue is kind of French isn’t it.

If somewhat impractical, in regards camouflage.

“Blue is kind of French”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prussian_blue

states that

[Preußisch Blau] was the predominant uniform coat color worn by the infantry and artillery regiments of the Prussian Army.[16] As Dunkelblau, this shade achieved a symbolic importance and continued to be worn by German soldiers for ceremonial and off-duty occasions until the outbreak of World War I, when it was superseded by greenish-gray field gray (Feldgrau)

The armies of the Ancien Régime wore mostly white, which was also a color of the Bourbon monarchs. Post-revolution armies usually had some or all colors of the tricolor in their uniforms, one of which is blue, so in that way blue was also a color used by the French. Blue was also the color of the Capetians in the middle ages, who created the first French national state.

It’s French, like onions, stripey tops and berets.

Recall that one effect of WWI was dispersion for simple self-preservation… Bunches invited artillery and machine guns. Combined arms meant in the end that wartime officers and even lowly NCOs had responsibilities for machine guns, grenade launchers, etc. that one were the preserve of company grade officers

Don’t forget… this photo has been hand-tinted. Real horizon blue doesn’t look that stand-out-ish in real life. I wear it a fair bit.

To answer to red trouser question, there is a story about merging friends and business.

The red fabric had been bought and needed to be used…

1903 : prototype grey-blue, then beige-blue mix -> both discarded

1911 : reseda green (supported by the ministry of war. But he died in a plane accident)

Then journalists and public opinion come to the ground, speaking about revenge for 1874, honor and stuff, so flashy red is compatible with prestige for them.

27th july 1914 : order to make horizon blue uniform

Franco-Prussian debacle, makes sense.

1870-1871: Many of the franc-tireurs had eminently practical uniforms modeled on hunting costumes, with the kepi still making an appearance, but also other campaign hats.

I have seen an 1897 propaganda book about Joan of Arc, clearly intended to instill a proper nationalist desire for revenge against the Boche. One of the lithographs has Joan of Arc in shining armor on a white horse leading French troops in their baggy red Zouave MC Hammer pants [it being “hammer time” vs. Germany, I suppose), the blue coat, red kepi, etc. Meanwhile, literally thrusting up out of the ground are the ghosts of the Imperial Guard in the tricolor outfits and bear-skin hats… Nothing about modern metalurgy, quick firing guns, machine guns, modern repeating rifles, etc. etc. Just “elan vital” and “cran/guts” and all that.

Chevalier’s novel _Le Peur/Fear_ seems to indicate civilian dress during basic training given the shortage of uniform items. Rather like the British soldiers with the Kitchener blue uniform in training.

As for things becoming “national”: the baggy red Zouave trousers are Berber/North African. The scarlet color Spanish (access to the “perfect red” cochineal dye of the New World) and English (New Model Army). the “stripey top” Breton, the Beret Basque, and so on.

WW1 FROM JULY,28,1914 TO NOVEMBER,11,1918. THE GREAT WAR. T

The horizon blue is definitely not the best colour for camouflage, but after a couple or days in the WW1 conditions, mud and dust and mud again gave a muddy colour to everything, including horizon blue uniforms.

Men in the trenches were usually said to be quickly turned into statues of earth.

Anyway, the real horizon blue (clean) was actuallly more greyish than pictured on this colorized view.

When combat was held at visual distance and communication was by voice, flags, musical instruments and runner/dispatches/couriers uniforms had to be colorful to be seen across the battle through the dust and smoke after firearms were introduced. It wasn’t until rifles became the dominate infantry weapon that armies realized that camouflage was needed.

Well that’s true. Before rifles became the main long arms, the smooth-bore muskets dominated. And unlike the popular myths of uninformed high school history flunk-outs, muskets had an effective range of about 100 meters, not 50 feet from your nose. Massed volley fire increased the effective range of a late 18th Century infantry platoon to about 400 meters (as in saturating the targeted area with lots of large caliber lead in order to harass the other team). Remember that war is NOT fought as a one-on-one duel. The original muzzle-loading rifles had one weakness: loading took at least one whole minute because the projectile required patching and a really tight fit down the barrel. Camouflage wasn’t a concern at that time, because it was thought that most battles would be fought in the open. It probably took lots of dirty fighting, weapons development, and massacres (and even lots of laundry bills) for the conventional western armies to consider simpler uniforms like battle-dress or fatigues. Steel helmets were reintroduced to reduce casualties from artillery shell fragments, and were not supposed to be bullet-proof (given the steel of the day, a hypothetical “100% bullet-proof” helmet might weigh up to ten avoirdupois pounds).

Did I mess up?

Yeah, you messed up…

The uniforms were a weapon, plain and simple. Of what utility is a force whose primary weapon is basically a threat display and intimidation, if you can’t observe that they’re there?

Pre-modern combat was largely a game of morale effect; the bayonet charge didn’t kill so much as it scared the shit out of the enemy, and they would flee their positions, leaving you in control of the field.

In that environment, the individual weapons were really more of a special effect to the theater of it all. How long, after all, were longbows more efficient killers than firearms–And, yet, the firearm was taken up in masses entirely unjustified in terms of actual physical effect. Psychological effects were more important than we are willing to acknowledge.

This was a truth of the battlefield, and a facet of war that the French excelled at for centuries. The problem was that the conditions of the battlefield changed under their feet, and what was a key factor in previous wars turned out to be a detractor under the conditions they actually faced.

I can’t blame the French for the choices they made; in accordance with past experience and their vision of how war worked, they made the right choice with both the old red and blue uniform, and with the horizon blue versions. From their standpoint, those were superior choices. The problem was, their vision of how things worked was wrong, and they didn’t adapt quickly enough to the changed circumstances. Hell, the French are actually the people who came up with a bunch of what became the German Sturmtruppen tactics–The thing was, the French Army was so sclerotic that they couldn’t take advantage of the adaptations which were trying to flow up from beneath.

The only really agile, adaptive, and flexible army of early WWI was arguably the Germans, against all stereotypes we like to hold.

It is quite arguable if longbows were ever more effective killers than early firearms. They certainly had much higher rate of fire and also somewhat longer effective range, in particular against lightly armored enemies, but on the flip side they ran out of ammunition more easily, arrows were more expensive than lead balls and their performance against heavily armored enemies in full plate armor or even brigandines (which even common soldiers often had during the Renaissance era) was not at all that great, historically dubious Hollywood depictions notwithstanding.

Also, firearms were much easier to use than longbows and you could train lots of musketeers in a couple of months, whereas it took much longer to train a longbowman capable of using a 100+ lb draw weight longbow effectively. Once technology enabled rapid production of firearms, the days of bows as general battlefield weapons were over.

I suspect a major factor in the decline of the longbow was the shortage of suitable bow staves . Centuries of harvesting had depleted the supply of one to two century old yew trees. No matter how effective they may have been there could not be enough of them.

It is said that the Duke of Wellington requested longbowmen to fight Napoleon, but was told that no such men existed in England. I have never found a reliable source for that though. Archery does have some advantages over 18th century musketry, such as rate of fire and ease for indirect fire (can’t fire muskets at high angles and reliably rain bullets on formations). However, archery is more difficult to train than musketry. Archery also isn’t impervious to the rain. Bows and strings made of natural materials change when they get wet. Arrows are also more expensive to make than bullets, powder, and flints.

Still, it would have been interesting if Wellington had gotten his archers. If they could have been protected from or kept away from artillery and cavalry, they could have done some good damage to infantry who had absolutely no armor or shields and who were unable to match the range of indirect fire by archery.

Good point about psychological effects.

It doesn’t even matter if you actually, physically defeat your opponent or not as long as he THINKS he has been defeated.

People back then also argued over the effectiveness of firing in volleys versus firing as individuals. Allowing individual soldiers to fire on their own allowed for more rounds to be sent downrange, but a volley was more psychologically devastating to an enemy. The idea that an enemy could be broken quicker when they saw all of the casualties at once from volleys.

Quite so — good observation!

By the way,your astute comment about volley fire and its immediate effects on the enemy’s perceptions and mindset from a psychological viewpoint reminds me of the artillery concept of Time On Target ( TOT ), whereby all the artillery pieces within range of a target time their firing intervals so that all rounds arrive overhead simultaneously. This has been repeatedly proven to be not only most damaging materially but also incredibly demoralizing to the enemy.

I’ve seen numerous examples of WWI horizon blue uniforms in museumsin in France and none of them were that bright. I think it’s an artifact of the colourisation technique.

The examples I’ve seen are all shades of grey ranging from shade similar to that used by the army of the Confederate States to a light blue—grey.

The article linked below has a run down of the variations and technology used in the construction of the fabric used for uniforms.

http://www.151ril.com/content/gear/uniforms/13

Yeah, but them Frenchies look good in powder blue.

Perhaps it was a form of camouflage because when they were covered in mud, they would ressemble a muddy puddle blending in with much of the ground, there wasn’t much greenry around in lot’s of places.

True, since everything had been bombed into nothingness. The horizon blue uniform actually doesn’t stand out if the viewer is over half a kilometer from the wearer and stuck viewing the battlefield through a periscope. The background of the battle would be mostly brown, black, and blue once artillery had blown away the greenery. By that point, it would be useless to wear anything green…

Those chaps stood up, are silhouetted against the sky. Looks quite a nice day, apart from the war.

Do you think multicam is to light, or is it sort of ambiguous at range not transparent as such but niether here nor there in most environments?

From what I have seen it tends to reflect what’s around it to a certain extent.

Perhaps the availability of German troops freed up from the eastern front didn’t really help the Kaiser, in that

Ludendorff always seemingly wanted total war… And in away, he had difficulties getting other Germans to agree- Total war resulting in the consequences Germany faced by 1945. So when he had finally got around to getting his own way, and he had the men. The stab in the back as he termed it, was possibly a consequence of folk bottling it. They figured losing was better, what did victory even mean by 1918. It’s arguable that they should have listened to him more earlier on, tactically. But by this time… Victory by, 1920, 1922. Happen they just believed it would be a phyrric one at best.

http://punch.photoshelter.com/image/I0000UVPUiXLb8Eo

When the German Army encountered the BEF in 1914 they complained that the British khaki uniforms were hard to see. Khaki is still a good general purpose subdued colour.

I think this multicam stuff, is to pale particularly after multiple washes for European environments. Perhaps a khaki uniform would be a better general purpose subdued colour, with material/printing technology these days theres no reason why they couldnt create exact camo matches to specific environments.

Disposable smocks, over trousers, fine ripstop mesh. Leaf print etc.

Quite like that Russian two tones of green patched affair. Desert Marpat looks pretty effective, as does Isis “kebab” pattern out there. Multicam seemed to suit Afghanistan on the whole, looking at it.

I don’t think so, we are using Multicam in mock Airsoft combat in Germany. In wooded areas it is much more effective in dynamic and fast moving games ( shooting distances are 50-90 yards) than the German Flecktarn, which really stands out as a dark silhouette when someone moves. Multicam is scaringly effective in hiding moving persons in Forests. Where there are patches of light and dark areas. Flecktarn however wins in stationary positions in dark pine Forrests. Multicam is however so much better overall. (Having experienced opponents with Flecktarn, Woodland, British DPM, Us Marines with their different Camos (Multiland?)

No doubt and forget all those silly-scientific camouflage patterns. That is, unless they accommodate surroundings on their own.

They could accommodate the surroundings on there own, printed photos of said surroundings. And the issued “uniform” compressed wouldn’t be any bigger than a can of coke. Possibly limits to this in regards it’s application, or deployment. But it could be done nowadays at least.

What about thermal camouflage, with the rapid advances being made in these sorts of sights. In the future optics might just see what can’t be seen. How to combat that? Have you ever seen ice cube making plastic bags, essentially a sandwich bag full of individual compartments that fill with water and seal themselves over all. Maybe something similar with Co2 gas… Cold gas. Could be developed as a over suit, to instantly inflate yourself invisible.

Wear long johns underneath like, probably be quite cold.

Regarding discussion of colour of fighting garb, it seem to me that most logical would be off dark brown. Look of sky-blue smeared with mud (and blood) must have been awful.

Yeah, and as someone remarked, the Tommy soldier looks just fine.

Dark brown is an overall good camouflage color **sometimes** but would of course be very visible in snow — an environment which can present its own set of challenges.

Snow in far northern latitudes, and especially in arid hilly areas, also presents another camouflage issue for mobile forces because snow often does not end up evenly distributed in many environments, especially as it melts. Snow drifts are one issue, and also because the sun will melt snow off the south side of hills — but not on the north side — that creates two separate visual environments requiring radically different camouflage colors for a soldier to be hidden on each side of every hill.

Russian, Scandinavian, and Swiss war strategists may have had to consider this problem more than anyone else. I wonder how they do it — quick-change white/brown reversible uniforms, perhaps? Keeping white fabric from turning dirty-brown would be another challenge in a long war.

I’ve seen pictures of Russian tanks (or was it APCs?) that reminded me of Holstein cows, but even that seems barely a solution.

Old Finnish M62 camo uniforms were reversible, with white snow camo on one side and woodland camo on the other side. This was okay, but since 1987 there have been separate snow suits. M05 system also has en intermediate “cold weather” camo which blends in quite nicely to patchy snow terrain in the Spring or frozen terrain in the Fall.

How about Woodland Camo for Europe? Worked before……

I think the old U.K DPM was much more suitable for Europe. Which was similar to U.S woodland in pattern, colour combination.

Our military has completely abandoned it though, they completely transitioned to multicam. Instead of having it as an option, like desert DPM for deserts. Doubtless it was cheaper, I believe multicam was sold as a all in one “modular” solution. Or the government wanted it to be. It clearly isn’t.

This video is a good example.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=0Z7OEgfqs8Q

At my time of service we were wearing this:

http://www.armyshop.sk/p/382/odev-maskovaci-vz-60-sada

There were pants in addition to what is shown. Fabric was reasonably resistant against wear/ abrasion. There were also liners top and bottom. Not bad overall.

Warsaw pact gear. I wanted one of those, well an East German rain drop coat with a fur collar at college.

I think modern gear is probably better, being more technologically advanced etc, although doubtless your older stuff was practical and sturdy.

There was no such thing as unified Warsaw pact gear/ field uniform. Every military had their own. What do you see in attachment is CS’s vz.60. Truth is that even reconnaissance troops had their own set.

Speaking of pre-Berlin wall East-German uniforms, they were available in substantial quantity in Canada. I checked them out, but was not truly impressed.

The padded splinter pattern jacket with the “fish fur” collar you mention also has a concealed pocket on the left breast side for a pistol around a Mak/ PP size. It’s a interesting jacket.

I think both sides of the argument we have seen so far are actually correct in their own way, for the reason that World War One was a transitional period that saw the gradual changeover from the traditional bright, obvious and visually/psychologically intimidating garb of the ranks about to overwhelm one’s own side on the one hand, and the adoption of the currently accepted better-camoflaged and more stealthy, if somewhat drab, approach on the other. What muddies the conclusions to be drawn from either approach is the fact that one or the other sometimes worked and sometimes did not, depending on the local situation and a whole host of related factors large and small. By the time the Second World War rolled around, the former approach was completely obsolete in the face of modern weaponry and the ability of the opposition not to be impressed, let alone intimidated, by the obvious visual grandeur.

On another note, it appears ( although I might be wrong ) that the original photograph in this article was probably colorized at a later date than when it was first taken. Either way, the blue-gray overcoats would still blend in reasonably well with the typical somber colors of the battlefield.

I agree. Certainly the mud and sludge adhering to the uniform would help blend in with the surroundings. In particular the shape of the helmet. During winters in the first years of the war, goat skins were worn over everything in many cases.

There are many French and some German color photos of WWI, all taken in rear areas for obvious reasons given the complexity of the process. So “WWI in color” offers a glimpse of some of the uniforms. The French Foreign Legion, many African troops, and some others wore brown French uniforms.

To my mind, the single most antiquated uniforms at the start of the war have to go to Belgium. I think that the appearance of Belgian forces would have been pretty similar in 1830 as in 1914, although of course weapons technology had changed drastically. Some German Landsturm had oil-skin hats that wouldn’t have been out of place in 1813…

I wonder how many of these poor fellows survived beyond November 11th, 1918? Less than 8 months later, perhaps, but in war 8 months might as well be 8 years, or much worse.

Here is little show of A-H military uniforms from WWI period. They were in reality little more grey than the picture shows. Gear of units of different nationalities varied slightly to reflect their ethnic tradition.

http://georgy-konstantinovich-zhukov.tumblr.com/post/41545029599/infantry-of-the-austro-hungarian-military-summer

Here’s an example of an original (non-colorized) color photograph of WWI French “Bluecoats” from a site that has many more:

https://worldwaronecolorphotos.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/www.poiemadesign.com_.wwi_.assets.images.db_images.db_83-110.jpg

I don’t know if it might have been due to patents or licensing issues, or whatever else, but for whatever reason the Europeans seemed to be far ahead of the Americans in color photogaphy in the very early 1900s.

Austria-Hungary really had a “muliform” more than a “uniform.” The colors could really be different: blues, grays, even browns… Cloth made from nettle fibers and so on, and lots of variability in quality.

The German uniform shortages also led to some rather unusual WWI combinations with the Landwehr, Landsturm, Ersatz, and Reserve units especially.

Color used in Austria-Hungary was called Hechtgrau

http://www.patriotfiles.com/forum/showthread.php?t=110038

but with due to:

1) limited industry power

2) many national units (remember that Austria-Hungary was multinational entity), which want to be distinct from rest

uniforms colors, details and style varied wildly.

During Russian Civil War shortage of all supplies was even bigger and there were many units fighting separately, thus uniforms and signs also varied. For examples of White Army uniforms see:

https://reibert.info/threads/uniforma-belyx-armij.91594/

This is good page and I receive information with trust. Indeed, uniforms of AH military varied quite a bit. They also mention the “Tyrolean backpack”. This worth of mention, because its lap was made out of calf skin – and used as pillow during field berthing.

The Great War series on youtube did an excellent, if brief and introductory, show recently on Russian uniforms. So many variations! Of course, there are the foot-wraps–one size fits all to simplify logistics–and as for a field mess kit, well, soldat Ivan, it is there on your belt: the entrenching tool, suitably cleaned, doubles as your frying pan!

According to Thompson’s _White War_ book about the Italian/Austrian front, to put the wind up the Italians, the Bosnian Muslim fez was the indicator that things were going to get “hot.” Just as the Scottish kilt was an unwelcome sign for the Germans… So the ethnic variations–what, 9 languages in the AH K.u.K.? is something that continued here and there even as French and Italian units increasingly became intermixed and therefore, “national” albeit with certain exceptions. The Italian Sassari Brigade, for instance, was all Sardinian.

There were two official languages in AH military. If inside the units some privates used their own it was tolerated but commands and reports were either in German of Hungarian.

My maternal granpa told me with dubious wink that Bosniaks had long bayonets. I am not sure if it was advantage for them, but they were respected part of KuK military. I happen to be last year visiting region of their and Italian enemies frontier; it is moving to see museums and memorials.

I noticed, there was a good deal of respect for either side. When Italians buried unclaimed Austrian soldier’s bodies they placed marker “Soldado Austriaco”. I am afraid we will not see this kind of chivalrous approach in near future.

Don’t forget that your compatriot wrote one of the most enduring black comedies about the war, thereby insuring that the “Good soldier Švejk” is the most famous fictional K.u.K soldier! Jaroslav Hašek’s novel/ quasi-biography.

Someday I’ll make a pilgrimage to the “U Kalicka” even if it is overrun by German tourists!

Emilio Lussu, A Soldier on the Southern Front translated from the Italian by Gregory Conti (NY: Rizzoli Ex Libris, 2014).

Mark Thompson, The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915-1919 (NY: Basic Books, 2009).

Film:

Francesco Rosi, Uomini Contro/Many Wars Ago (Italy/Yugoslavia, 1970 Raro Video http://www.rarovideousa.com).

WWWeb:

http://www.talpo.it/SIPE.html#

The assault! Where were we going?

We were leaving our shelter and going outside.

Where? The machine guns, all of them, lying on their cartridge-crammed bellies, were waiting for us.

Anyone who hasn’t experienced those few seconds has not known war. (p.120)

“Basta! Basta!” “ Enough!” cried out the chaplain of the Imperial and Royal army of the Hapsburg “dual monarchy” from the rocky frontline trench to downhill enemy Italians—fellow Catholics “… brave soldiers, don’t get yourselves killed like this!”(p. 123) Mark Thompson’s research, published in his 2008 book about the Italian front in the First World War, The White War, found that such pleas from Austro-Hungarian troops surveying the shocking carnage wrought by artillery, grenades, mortar bombs, Schwarzlose machine guns and Mannlicher repeating rifles were more common that might otherwise be imagined.

“Svejk” being a classic of antiwar parody has somehow tainted image of Czech men as fighters (never too good at it unless in extreme necessity).

The novel (actually whole set) is placed around events on Eastern front. Czech were not willing to fight Russians (result of Pan-Slavism of 2nd half of 19.century) and there were instances when whole battalion marched over to enemy side. Those created later Czech Legion which were very successful in fighting Bolsheviks.

But, on southern front the situation was quite different. It is documented that Czech soldiers were fighting even after day of official armistice. Their bravery in difficult circumstances were undisputed and in fact recognised by Austrian command.

When comes to Czech beer and its quality, it is apparently on downslide since factories were acquired by foreign (global) financial power. Czech beer available in Canada is so ridiculously watered down (so called “light” to suit N/A customer) that in does not get my attention at the slightest. My favored brand in Ontario own.

Duplicity of fighting fellow Italian Catholics came under scrutiny of many and as a result vast majority of Czechs, after end of WW1 and creation of new country, quit Catholic church in favor of newly created protestant faith branch called aptly Czechoslovak church.

“Czech men as fighters”

See генерал-майор (equivalent of US 2-STAR GENERAL) Vojcechovský

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sergei_Wojciechowski

which lead Великий Сибирский Ледяной поход through iced Baikal lake, after death of генерал-лейтенант Каппель (not to be confused with «Ледяной» поход lead by генерал Корнилов through Кубань)

Bear in mind a couple of things about vintage “color” reproduction. While there were a couple of color processes existing in 1918, none were really very good and all were hideously slow and/or cumbersome.

Colorization is mostly done by a techno-geek assisted by a computer rendering results based on a best guess as to what the original color in question was in 1918. True, one can match an original swatch, but wait…That swatch is a century old now and is most unlikely to be very close to its original color. Especially material made by a low-bid provider and expected to last…well, not long in the trenches of WW 1.

Just to make the comparison more interesting, ‘colorization,’ by definition, is taking a black and white image and adding color largely based on the grayscale of the black and white tonal scale.

For modern panchromatic film that usually means red is a medium to lighter gray, while a blue object is usually a darker gray. But in 1918, there was no panchromatic film. It was orthochromatic, meaning it was blind to the color red which reproduced as black or very dark gray. And just to make things even more unfathomable for our techno-geek trying to make the colorization process work, most of the films or plates in 1918 were unnaturally sensitive to the color blue. (You’d be surprised how few of the otherwise technically adept know this bit of (now) arcane trivia.)

So that’s why the blue skies were usually bleached out, blue uniforms never looked right on Union Army Generals (looked bleached) and our French soldiers seem to be dressed in electric blue or illuminated from within.

As an addendum, this has often been the cause of misidentified vintage aircraft, vehicles, buildings, ships, even whole towns or nearly anything with a sign on it.

It drives anybody working from vintage images nuts.

Like serious modelers and reenactors. And those that restore or hand-tint vintage images.

Like me. ;D:):)

Great information — thanks for sharing!

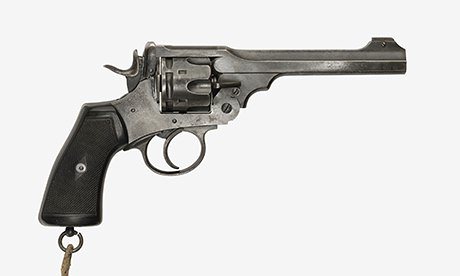

I have asked before … i’ll ask again … after trading several old revolvers, in an effort to update to a smaller carry piece, I purchased a new Ruger LCP. Then, when experiencing a “misfire,” questioned both CCI Speer (manufacturer of ammo) and Ruger about the issue. Sent the weapon back to Ruger, upon Ruger’s request, for examination and testing. CCI Speer requested the ammo back for testing and QC evaluation. The ammo company said the Ruger fired “off center” and that caused the “misfire”. While each were doing their thing my old 32 Spanish Eiber was substituted, until the firing pin “fell out” while reloading and checking the breech.

The gunsmith called it a “Park 1903”. Any one know why he called it a “Park?” …. also was it made in 1903? … Would the date of manufacture have been stamped somewhere on the inside of the weapon?

Both have been substituted with a “Bersa Firestorm.” The 32 Eiber will be repaired in a few weeks. Any one know anything about these weapons? If so, your comments sincerely appreciated. Thank You.

There’s a page on this site about Spanish pistols made in Eibar. Some based on the Browning 1903…

https://www.forgottenweapons.com/other-handguns/eibar-ruby/

Can’t find a Park, Harrington & Richardson had a factory on Park Ave. Maybe they imported them, haven’t found out currently… Spanish pistols were made for the U.S market seemingly, but perhaps it was a French WW1 contract model imported from France as oppose Spain.

Park is spelt pretty similarly in Spanish and French, so it is probably an English term. Possibly a colloquial reference to a company, based on it’s headquarters.

Same in Italian, parco. Parques de artilleria means artillery depot. So maybe it refers to an industrial park, for firearms in Eibar. As oppose a park, that you walk a dog in. Parker and hale? You’ll have to ask him why he called it a park and tell us.

I WAS WONDERING IF THE FORTUNES OF THE ALLIES WOULD HAVE IMPROVED IF ALL SIDES WERE USING ONLY ONE CALIBRE AND ONE RIFLE FOR THE ENGAGEMENTS …PERHAPS THERE WOULD NOT HAVE BEEN THE LOCK JAMS WITH LOGISTICS.

JUST A THOUGHT

LENIN

Certainly… But of course, the Allies couldn’t agree on very much, except to urge the other to do more and take on greater exertions, longer sections of the front, etc.

Foch only becomes a supreme commander, like Eisenhower in WWII, in what? 1917? or as late as 1918?

Even under Nato and the Warsaw Pact there are some odd refusals… France simply already had ample war stocks of 7.5×54 and so kept it… Nato might have thought of standardizing on the French caliber insofar as the British .280/7x43mm idea was scotched by the 7.62x51mm… And while the Czechs sort of grudgingly adopted 7.62x39mm after the communist take-over, the magazines of their VZ58 are incompatible with the Soviet Kalashnikovs.

When the US entered the war (1917), to avoid logistics problems, they adopted french and british caliber for their artillery:

37mm, 75mm, 155mm, 8 inches, 9.2 inches…One exception was the 4.7 inches M-1906 gun.

As far as i know 30-06 was being used by the french aviation (alongside .303)and so wasn’t a problem.

As for post WW II, don’t forget the Swiss with their 7.5×55 mm STG57 until 1990 and now the Chinese with their weird 5.8×42 mm.

Thanks. Yes, certainly the case. While Pershing held out for an actual U.S. held sector of the line for an American army, and oversaw battles like St. Mihiel and the long and bloody Meuse-Argonne at the request of Foch, he did not entirely resist the Franco-British insistence that Americans serve as replacements and reinforcements to their sectors.

Thus, there were U.S. forces who served alongside British troops and used .303″ Vickers MGs and so on, and black regiments–famously the NY National guard unit, the “Harlem Hell fighters” who found under French command, wore French helmets, and carried Berthier rifles and wore French load-bearing equipment even while they had U.S. uniforms, roll puttees, etc. etc.

The 8x50mm CSRG Mle. 1915 automatic rifle was the “standard” LMG until quite late in the war, when BARs started to become avilable, as did Browning MGs in .30-06. Most AEF doughboys carried the M1917 rifle rather than the M1003, although apparently the 5th and 6th regts. of the USMC–“Teufelhunden” or Devil dogs–carried the M1903.

The advantages of high-visibility uniforms were probably lost by the time of the American Civil War. Armies still trained and maneuvered along Napoleonic era (or even older) tactics that assumed the need for volley fire, and a maximum practical range of 100 yards or so.

Rifling and percussion firing didn’t make troops any faster or more cool-headed, especially the conscripts in 1861-5. But the effective range went out to at least 500 yards. All the standard infantry tactics were suicidal if they had to be carried out over the extra 400-500 yards of killing ground.

Let me point out that the Commandant of La Legion Etranger during the Great War, General Rollet (“Le Pere D’Legion”), was always considered an odd ball as he insisted in wearing his khaki African uniform on the Western Front. Here he is with the Legion’s Color Guard at an awards ceremony

https://www.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=2D8RDUmF&id=9B6A7CA96857E32A43B24EDF54C110FC1A4341B6&thid=OIP.2D8RDUmFYWIDWCMuaxl36QHaKF&mediaurl=https%3a%2f%2fmonlegionnaire.files.wordpress.com%2f2011%2f06%2fcolor-guard-1re.jpg&exph=816&expw=599&q=general+rollet&simid=607990805780169289&selectedIndex=24&ajaxhist=0