Related Articles

Conversion

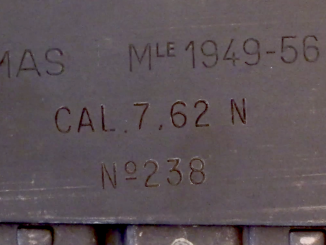

French NATO Standardization: the MAS 49-56 in 7.62mm

Preorders now open for my book, Chassepot to FAMAS: French Military Rifles 1866-2016! Get your copy here! In the late 1950s, France was still part of the NATO integrated military structure. When the 7.62x51mm cartridge […]

Light MGs

8mm M1915 Chauchat Fixing and Range Testing

Well, my 8mm French Chauchat finally cleared transfer, as did my application to reactivate it. This was a “dewat”, or “Deactivated War Trophy” – a machine gun put on the NFA registry but modified to […]

Semiauto Rifles

Gevarm A6: An Open Bolt Semiauto .22 Sporting Rifle

Gevarm, a gunmaking offshoot of the Gevelot cartridge company, produced a line of open-bolt semiautomatic rimfire sporting rifles from the early 1960s until 1995. This is an A6 model, the base type. It is chambered […]

Judging by the receiver, that has to be a Lebel. The Berthier wasn’t popular because of limited ammunition capacity and its tendency to jam in mud… Or am I wrong?

The Berthier 07/15 model with five-shot Mauser-type magazine had virtually replaced the Lebel as the standard rifle of the frontline forces by mid-1916. By that time Lebel production had ended, and the Berthier was to be the new default standard rifle.

This was because the Lebel was too difficult and complex to produce rapidly enough for the French Army’s requirements by that point, and also because the Lebel was even more prone to jamming in Flanders mud than the Berthier. Most obviously, the tubular magazine was much more difficult to clean out once mud or water got inside, requiring the rifle be completely dismantled to do it.

In the mid-1930s, existing stocks of both rifles were reconditioned for issue to reserve formations that weren’t getting the new MAS36 rifle in 7.5mm. This revamp included shortening them to carbine length (reducing the Lebel’s magazine capacity to five rounds), fitting any Berthiers that still had three-shot Mannlicher-type magazines with five-shot Mauser types (actually more like a Mosin-Nagant’s), and in some cases rebarreling the Berthiers to 7.5mm.

But not the Lebels; the 7.5mm round’s spire-point bullet and tubular magazines don’t mix too well.

There rifles were used extensively by the French Army up to the surrender in 1940. After that, they remained in use by internal security forces. After the war, they tended to show up all over the place as the French army got rid of its more embarrassing “assets”.

cheers

eon

And yet for all of that the French Army’s leadership left much to admire, even when the guys managing the equipment got some good gear like the FM-24/29 and the various tanks which actually matched or outdid the panzers of the Reich. Various accounts state that the Panzer III variants invading France had a hard time dealing with the FCM 36, which itself was only well equipped for dealing with infantry. The Panzer IIIs won only after smashing into the FCM tanks and shooting until the latter’s armor welds failed. In essence, most tank fights in the Battle of France that involved German tanks and French tanks devolved into a wimp fight unless heavy anti-armor guns were brought in to end the brawl.

Even while an armistice was being signed, many French units did not surrender. Those units were too busy kicking the Italians, whose preparations for invading through the most ridiculously heavily fortified mountains of southern France were completely inadequate… Or am I wrong again?

The French had some good ideas and some bad ideas when it came to tank design after WW1. Their best idea was to give even light tanks decent amount of armor, and of course their medium tanks were very well armored as well. Their worst idea was to favor small one man turrets even on medium tanks, which made the commander/gunner/loader incredibly overworked and basically unable to both lead and effectively engage the enemy with the main gun. Of course everything in a tank design is a tradeoff, and the small turrets largely enabled the excellent armor while still keeping weight in check.

The main gun of most of the light tanks was, like you wrote, also a problem, since it was based on the WW1 37mm infantry gun. French tank doctrine, like everybody else’s in the 1930s, was that enemy tanks should be dealt by towed anti-tank guns, so a better gun for dealing with enemy armor was not needed. They did realize this was perhaps an error and developed new armor piercing ammunition for the gun in the late 1930s. The result was world’s first APCR (Armor Piercing, Composite, Rigid) production ammunition. Unfortunately it could only make a terrible gun somewhat less terrible and it was not available in sufficient numbers by the German invasion. The ballistic coefficient was also quite poor (a problem with all APCR type ammunition), so effective range was limited to about 300 meters.

French light tanks also didn’t have radios, although in 1940 only German and the still very small number of US light tanks did. The radios on medium and heavy tanks were unreliable compared to German and British ones, and commanders couldn’t really rely on them to work.

” Their worst idea was to favor small one man turrets even on medium tanks, which made the commander/gunner/loader incredibly overworked and basically unable to both lead and effectively engage the enemy with the main gun. ”

It’s funny that tanks are coming full circle, with the new Russian T-14 Armata tanks down to a crew of just three.

Soviet/Russian tanks have had three man crews and and two man turrets since the introduction of the T-64 in the 1960s. The loader was replaced by an autoloader in that model and the T-72, T-80 and developments (including the T-90, which is a T-72 development). From western tanks the Swedish S-tank and the French Leclerc have or had autoloaders and three man crews. (The turretless S-tank was retired in the 1990s.)

That’s right, I think I may have read too many “The Russians Are Coming!” articles that my mind clouded over. Comparing the Armata with the Abrams, they mention the T-14’s auto-loading (unmanned) turret and smaller crew compared to the Abrams, but fail to mention that it’s been that way for half a century. Oh well, “facts” on both MSM news and propaganda has always been short of context, and either (when they’re not one and the same) can have a numbing effect on the mind.

aa & E;

The Armata has augmented turret armor and an unmanned turret, as I understand it. For their sake I hope so, as the autoloader system used up through T-90 always had a live round in the tray behind the breech at all times.

Which meant that any penetrating hit to the turret tended to set it and the shell racks off, resulting in the classic “catastrophic kill” so often seen in the MidEast, with the turret blown off the hull and the interior reduced to ashes.

Including the tank crew.

cheers (?)

eon

“French tank doctrine, like everybody else’s in the 1930s, was that enemy tanks should be dealt by towed anti-tank guns, so a better gun for dealing with enemy armor was not needed.”

French doctrine, similar to other nations inter-war doctrines, say that there are INFANTRY TANKS and CAVALRY TANKS, first were slow, well-protected and armed suitably for attacking infantry – for this role 37mm short gun was enough, when second were faster and better armed to fight against other tanks – SOMUA S35 has 47mm main gun with much better penetration.

—

Main problem of French forces was not lack of tanks, but being unable to move them where they are needed.

Daweo; I agree, a good clarification. The cavalry tanks were intended for exploitation and rapid counter-attacks, which meant that they should be able to fight enemy tanks without the help of anti-tank guns. There wasn’t enough of them for general anti-tank duties, however, and that’s where the towed guns were essential.

There was also a third class of vehicles, namely the heavy breakthrough tanks represented by the (Char) B1 and B1bis (plus some older obsolescent vehicles). Their job was to act as the point of attacks, which is why they were equipped with a 75mm howitzer to destroy enemy anti-tank guns and strongpoints. You could say that they were a sub-class of infantry tanks rather than a completely separate class of tanks, but that’s semantics. In any case it is notable that both the Soviet KV and IS series and the German Tiger were conceived for similar roles. The Americans also had the M6 heavy tank, although it was never used in action.

“(Char) B1 and B1bis”

Which proved be superior in combat against German tanks, see for example:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Billotte#16_May_1940

—

Other flaw of French design (linked to one-man turret) has impact on combat effectiveness: many French tanks don’t have radio equipment – simply in two-man there is no-one to do that – driver need to steer vehicles and loader/gunner/commander as you pointed was overloaded with job even without using radio communication. Lack of radio set lead to low awareness and make commanding any bigger formation of tanks tricky

The B1bis was a very good tank apart from the single man turret and cost. The howitzer in the hull had no horizontal traverse but instead the gunner had controls to turn the whole tank very finely. The system worked reasonably well, but it was quite expensive to make. Such system would not be utilized in production vehicles again until the Swedish S-tank in the 1960s.

eon– I was under the impression that the 3-shot Berthier rifle was replacing the Lebel from about 1915 on, and that the 5-thot only began arrive in 1917 alongside the self-loader, and that 5-shot Berthiers were by no means common until quite late in the war, like 1918?

The Lebel had actually been entirely produced before WWI, and so only parts, stock fittings and so on were produced, while the 3-shot 07/15 was rushed into production, and later the 5-shot modification, adopted only in 1916 but with a lag time.

As for WWII, the Germans apparently were some of the last users–along with the odd NLF/VC in SE Asia, of the Lebel. It was issued to hapless Volkssturm at the end, although mostly to those close to the French border. I have a photo someplace of bicycle-borne German troops on occupation duty–possibly guys previously exempt from military service for flat feet or whatever, armed with long Lebels.

Hi

Just a few points for the Berhier long rifle.

-By mid-1916 only Berthier rifles were produced, but Lebel were still widely in use until the end of the war. Half -Half in frontline. A photo of French Foreign Legion soldiers by mid-1918, shows them with Lebel 1886M93.

-The Berthiers became the standard rifle officially in 1917. But they were slow to replace the Lebel.

-During the may-june 1940 campaign, Berhier in 8mm was the standard rifle, both in the 3 shots configuration (model 07-15) and 5 shots configuration (model M16). There was only 240’000 MAS36 avalaible for an army of little more than 2 million soldiers.

-The Berthier M34 with a 5 shots Mauser style mag were in 7.5mm, not in 8mm. Berthier 07-15 were shortened to 98K legnth and converted with new mags (looking like Mosin/Mauser mix) and barrels, as you said.

-Both the 07-15 and the M16 had Mannlicher style magazines.

-Still today it’s unknown precisely how many “pure” 5 shots long rifle had been produced from mid 1918 to mid 1919 ( 300’000 ???) and how many 3 shots 07-15 have been converted to 5 shots M16 configuration from 1919 to 1940 (maybe 300’000 of the 1’200’000 07-15 produced during the great war ????).

As you can see, following ww1 and interwar french rifles story, gives headache

Regards.

Jeb

The Berthier rifles with 5 shot magazines weren’t introduced until late in 1918. The mousquetons were being made with the 5 shot magazines in 1916 or 1917 (in fact the very first M16 marked mousquetons came from the factory with 3 shot magazines as production of the magazines hadn’t caught up yet).

The Lebels that were cut down to carbine length only had a 3 shot magazine, but you could put one in the chamber and one on the lifter. DON’T DO THAT NOW or you might break your extractor and good luck finding one! There was also a very few Lebels that were converted to 7.5, but those had a different magazine. Those are really rare as they were too expensive and time consuming to produce.

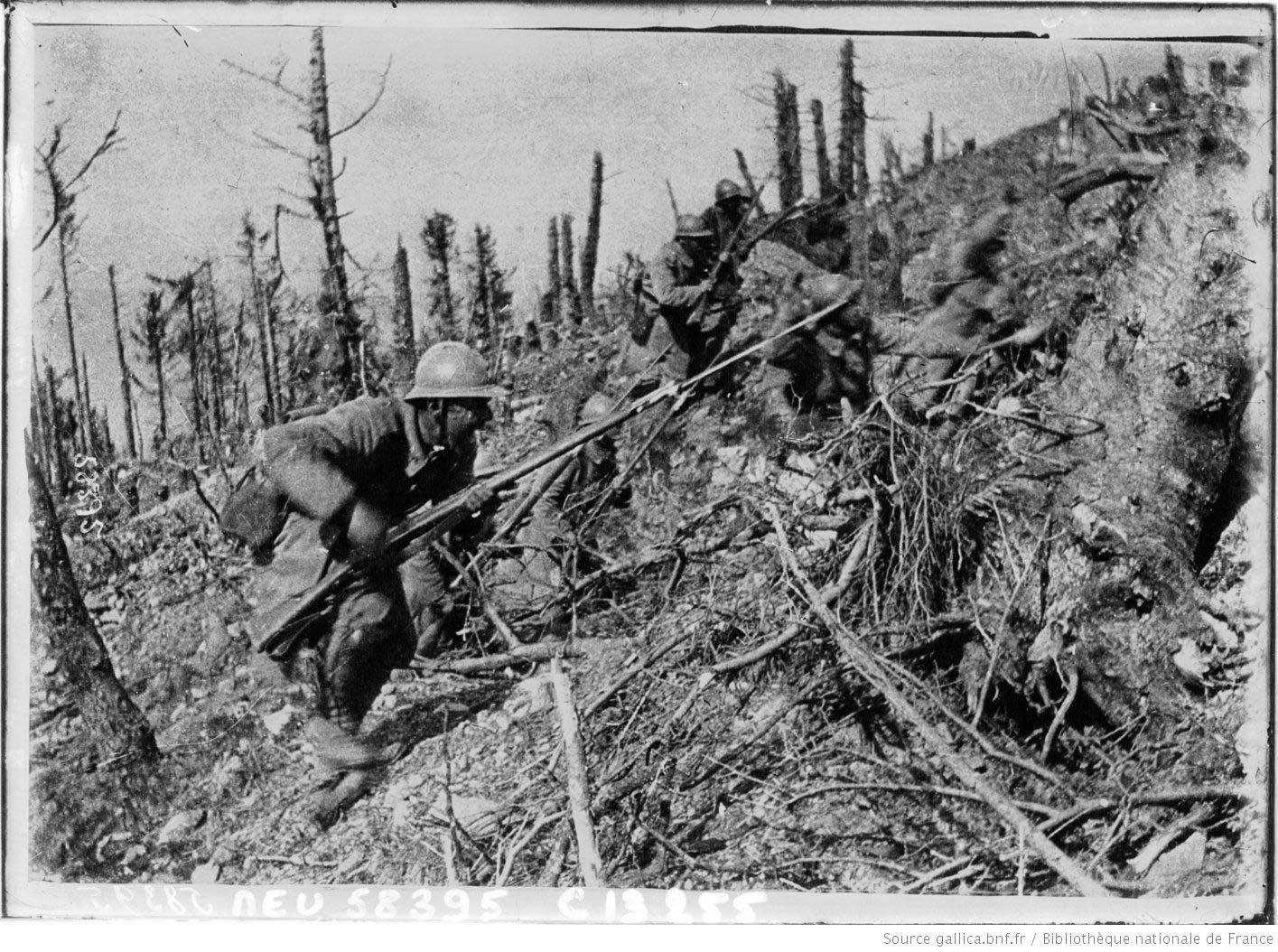

A moment it time…frozen forever…6 men visible in that image…doubtful they survived.

Bayonet design is a topic that tends to get glossed over by “gun people” while largely ignored by “sword people” but that hardly means it doesn’t have an interesting development history, with the wide variety of different bayonet designs that have come and gone since the flintlock era.

It would seem to me that the *ultimate* bayonet would have been one that could open like a switchblade (with the release on the breech end) with the rifle still shouldered, but I don’t know if any rifles were ever designed that way. (a ‘switchblade’ rifle might even be considered illegal here in the US under both federal and state laws that sprang up across the country during the 1950s Hollywood-created switchblade panic; just convince a judge that gun+bayonet=”knife”)

The Italians had a “switch blade” bayonet for the Carcano rifle, but it seems to be a dead end for obvious reasons. If the blade exceeds handle length you must have special cutout in the rifle stock…

“The Italians had a “switch blade” bayonet for the Carcano rifle, but it seems to be a dead end for obvious reasons. If the blade exceeds handle length you must have special cutout in the rifle stock…”

That’s assuming the gun used a knife or sword type bayonet — but many (if not most) did not, particularly during the muzzle loading era, for apparently obvious safety reasons.

It would seem like those triangular blunt-end bayonets could have been easily rendered harmless by a decent breastplate, or maybe even just a piece of thick leather, so it’s a wonder that style lasted throughout the era of the bayonet charge (until in-trench combat would have showed the obvious superiority of blade bayonets over spike type when the soldier’s back was against a wall).

A decent steel breastplate would stop pretty much any edged or pointed weapon no problems. For going through a breastplate you need a spike point with heavy head such as a warhammer or poleaxe, which were popular during the late Medieval and Renaissance period. Breastplates were in fact still quite popular in the 17th century just because they could easily stop a pikehead. They were slowly abandoned due to their weight, cost and uselessness against musket balls.

“Spring” or “switchblade” bayonets were common on blunderbuses in the late flintlock period. That was because the blunderbus was essentially a “riot shotgun”, a CQB weapon. Its wide muzzle wasn’t to “spread the shot” (it doesn’t), it was to make it easier to reload in a hurry, like pouring powder and shot down a funnel.

The spring bayonet was in event the target was so close he tried to grab the gun or grab you before you could reload.

You often see similar but smaller spring bayonets on pocket pistols up to the percussion period, as well. For the same reason.

cheers

eon

Speaking of getting personal, didn’t some jungle fights of WW2 devolve into huge knife fights where both sides whipped out bladed weapons (bayonets, machetes, kukris, and the like)? If your objective is stealth, don’t take a gun…

I have never read about such thing on a wider scale, unless you mean the few times Japanese succeeded in doing a stealth night attack. In such cases the defender would try to use firearms as much as possible, but the close ranges might have prevented it at first, rifles being fairly long. While on patrolling in the jungle such fights may have occurred, although I don’t see why both parties would like to avoid gunfire. In case of the Japanese the large scale use of bayonets was brought by doctrine, but also by the fact that by and large they didn’t have submachine guns or semiauto rifles.

Actually, the major proponents of blades in that part of the war were the ANZACs, who picked it up from the Gurkhas.

Night patrols were instructed to use silent kill techniques whenever possible, to avoid giving the Japanese any warning of their presence or any idea of their numbers. (The Anzacs were almost always outnumbered, especially in New Guinea, even with the locals helping them.)

Rather than any special blades, the standard issues bayonets, “jungle knives” (machetes for cutting through brush) and whatever could be acquired were used.

Like most armies, the “spike” type bayonet being issued for the SMLE and No.4 rifles resulted in soldiers acquiring sheath knives ASAP. Not so much for combat, as simply because a triangular spike with a needle-sharp point and no actual cutting edge make look cool and menacing on the end of the rifle, but it’s utterly useless for all the mundane camp chores for which a strong, sharp, fixed-blade knife is indispensable. Opening canned food, cutting firewood, whittling tent pegs, whatever; you can’t do it with an overgrown hatpin.

The same thing happened in the American Civil War. One of my ancestors who served with the 1st Ohio Volunteers (Infantry) wrote home to tell his family and friends that every enlistee needed three things in the “edgeware” department; a good folding pocketknife with a sturdy blade, a camp-type knife/fork/spoon combination, and a sturdy “side knife” with at least a six-inch blade.

Why?

Because, he explained, the standard epee’-pattern bayonet for the .58 rifle-musket had exactly three practical uses in camp.

As a roasting spit, a candle holder… or a spare tent-peg.

And yes, this is why Theodore Roosevelt so strongly disapproved of the retractable “rod bayonet” on the early model M1903 Springfield rifle. It might skewer an enemy soldier, but it was no use at opening a can of peaches.

And as an experienced outdoorsman, he considered the latter far more important than the former.

cheers

eon

Good point about the ANZACs. One side of patrol vs. patrol combat usually does have a motivation to keep the action as silent as possible. Usually the one closer to enemy front or base.

The uselessness of spike bayonets as general tools is well documented. Not that long sword bayonets were much better. A short sword is not a great tool, since it’s too long and unwieldy for most uses of utility knives. Hence the proliferation of knife bayonets post-WW1, albeit their utility as general knives varied a lot as well.

Re the comments about ANZACs in New Guinea – there were not many, if any, New Zealanders involved on the ground in NG, since the NZ Army remained in Europe, especially Italy. Thus there could not have been ANZACs on the ground, only Australians and Americans. I have really not heard of widespread use of blades in the way described, since the fighting was largely quite mobile much of the time. Thompsons and Brens were the weapons of choice for Australian units in the thick jungle. As for being outnumbered, the Australians were heavily outnumbered for the first months of the Kokoda campaign, but this was eventually rectified and the Japanese were outnumbered thereafter, and at Milne Bay they were heavily outnumbered by Australians and Americans. While there was bayonet fighting by Australian troops in NG (I think Eora Creek Battle was an example), it was more common in North Africa and Crete (see the Battle of 42nd Street for an example), and there they often were ANZAC units.

I have a flintlock pistol with such a spring-loaded bayonet. After firing (or before, it’s entirely the user’s choice) the trigger guard is pulled to the rear and releases a catch holding the blade folded. A very clever, clean design.

I always remember the incredibly sage advice of my basic infantry instructor on the subject of being attacked by say, a 6 foot plus Japanese Marine with a 14 inch bayonet on the business end of an Arisaka.

“What to do?” sez newbe me.

“Well, Troop,” sez the nearing retirement age, ww2 combat vet with actual real life experience in this very thing, “you reach into your pants, pull out a big handful of S**T and throw it in his face, then…

“But Sarge,” says the newbe (me,) “how do I know that’ll be there?”

“Don’t worry, young troop, somebody charges you with a 14 inch bayonet, the S**t will be there.”

Or just hide behind a machine gun and let him have a shower of copper-jacketed lead. Barring that, sidestep the attacker, grab his rifle in order to transition to melee, then kick him in the unmentionables. After that kick, yank the weapon from your opponent and then stab him with it.

When it comes to actual bayonet fights, it turns out most terrorists actually flee when their opponents start getting personal with blades. In fact, I would assume that the best way to scare over-indoctrinated extremists in the Middle East would be to ambush them in their sleep using only cold steel. How would I know? The Poles actually did this and nearly exterminated a panzer division in 1939. Nobody expected supposedly-defeated Poles to sneak into a town occupied by Germans at 9:30 at night and then begin stabbing the Germans in their beds… Did I mess up?

If someone with decent amount of training attacks you with a bayonet fixed to a full-lenght rifle on open terrain, and you don’t have firearm or at least some reasonably long close combat weapon ready (like a rifle even without a bayonet), you are in deep trouble indeed. Even with an unloaded rifle without a bayonet you are on a considerable disadvantage, but at least you have something to parry with.

Sidestepping a bayonet (or spear) point is one of those Hollywood-favored techniques that requires lightning fast and correctly timed execution in real life. The likely outcome of it is you getting stabbed. Only in the hand or arm if you are fast and lucky, but quite likely somewhere where it hurts more. If you have no better weapon than a knife or say, empty handgun, your best chances are running and trying to find something to shield you from the attacker, like a tree, or simply outrun him and find some cover before he has time to reload his rifle. In actual combat you could also hope for your buddies to save you.

As Heinlein pointed out in Time Enough For Love, bayonet fighting is a nearly lost art, and one with which its skilled proponents can do a lot more damage a lot faster and with a lot less noise than you’d expect from Hollywood.

It’s a cross between polearm and axework, most closely resembling the Roman legionary’s use of the pilum or the use of the Saxon bill or Japanese naginata. It only slightly resembles lance or spear work, as it is both a stabbing and cutting weapon, assuming the bayonet is an actual blade and not a knitting needle on steroids.

Also, the rifle can be used like a quarter-staff or bo stave to deliver striking blows, a s well as counters to incoming strikes. And again as RAH points out, a counter is faster, more deceptive, and more damaging to the opponent than a simple block.

This of course assumes a rifle of adequate length and sturdy enough structure, like the SMLE, Garand, Springfield, Mauser, Mosin-Nagant, or Arisaka. I wouldn’t recommend trying it with an L86, AUG, G36 or any M16 variant. (I’d be dubious about trying it with an MAS36 or Italian Carcano, for that matter.)

BTW, the old story about “If you try to block a ‘samurai sword’ with a Garand, it will cut the rifle in two” is a myth. While some highly-prized blades such as those by Masumune might be physically tough enough to cut through wood and ordnance steel, few men have the strength necessary to swing one with enough force to make it work.

And few such blades were ever seen on the battlefields of the PTO, anyway. Most “officers swords” were shingun-to types, mass produced mainly as badges of rank for officers below flag level.

I’ve examined several such, over the years, and frankly, the ones you find in “martial arts shops” or at flea markets for under $50 today have better-quality steel in their blades. Most are so “soft” they’ll barely hold even a relatively coarse edge.

No wonder every Japanese officer after about mid-’43 wanted any handgun he could get hold of. Or better yet, a rifle.

The ones who thought “the sword conquers all” were gone by that time. Mostly having fallen victim to Allied soldiers’ rifle fire.

When Admiral Yamamoto said of the then-new battleships Yamato and Musashi, “They are as much use in modern warfare as a katana“, he didn’t intend it as a compliment.

cheers

eon

I agree with your points in general, though the pedant in me must object to the inclusion of the pilum in this case. Throwing spears with no cutting edges could certainly be used as bludgeons and thrusting weapons but not as cleaving weapons. That’s what the Gladius and spatha were for! And of course in the latter centuries the Pedites had adopted battle axes on a wide scale as well.

I think it’s safe to say that the fighting style used with a bayonet depended on it’s shape, but primarily it has always been a thrusting weapon. Naginatas and glaives had a curved blade, which made them noticeable better push or draw cutters than a typical straight sword bayonet blade. The balance of a rifle-bayonet combination also isn’t optimal for hacking, unlike a bill or halberd. You can of course still cut or hack with any sharp-edged weapon.

Fighting manuals for 19th century and even earlier bayonet fighting have been preserved, although like aa wrote, they are not yet studied as widely as the more romantic Late Medieval and Renaissance combat treatises. Hobbyist interest in 18th and 19th century military sabre combat is rising, though, and bayonet combat is a natural counterpart to that.

Eon,

Heinlein was a Navy officer who never saw combat. I’d hardly consider him an authority on bayonet technique.

Objectively speaking the “best” bayonet technique is the Japanese style (they notably humiliated the British at an international competition in the 1920s among other things) which is almost entirely based on thrusting. Ironically, after decades of speaking contemptuously about Japanese technique the US Marines recently filed the serial numbers off and adopted exactly that approach for the bayonet portion of their combatives program. The “Western” techniques of beating someone with a swung or jabbed buttstock are more useful for crowd control than actual combat – the only “kill” shot that you will get out of them is a hard blow to the head and actual soldiers wear helmets. So I also wouldn’t take the pre-combat comments of people who quickly figured out that you don’t get into bayonet fights with the Japanese and live as authoritative either. 😉

If you were examining “Japanese officer swords” that seemed to have notably awful blades you were probably looking at Chinese forgeries. There are many on the market and “non-sword” people looking for a piece of history are the target audience. It’s not exactly spoken of in Japanese sword circles, but I’ve gotten the quite strong impression over the years that the “nontraditional” gunto were actually perfectly fine swords and hardly distinguishable from traditionally made models. Steel is steel after all and doesn’t know if the hammer hitting it is powered by machinery or muscle. The example of Arisaka rifles may prove instructive.

see: http://www.japaneseswordindex.com/repro.htm

Armchair Overlord: using the buttstock as as club can be useful if the opponent has gotten very close and thrusting becomes difficult. Quite often you can, however, thrust at an opponent downwards at his legs even quite close. In a bayonet vs. bayonet fighting there really is seldom use for such techniques, because both sides should want to keep their distance at the most effective range of their weapons. Voluntarily closing in with a relatively long thrusting weapon is of course simply dumb.

As for the Japanse mass produced officers swords (shin guntō): they were at least initially made to the same standards as the European sabre style kyū guntō, which according to everything I have read was a pretty good sabre. Some were apparently even made using the traditional pattern welding techniques, but most were machined carbon monosteel like the kyū guntō sabre. High quality monosteel swords are of course in many ways better than pattern welded ones, with slightly lower edge hardness (typically) being the only significant drawback compared to the traditional Japanese swords. There were some really bad Japanese mass produced WW2 swords no doubt, but they seem to have been late war NCO swords.

“The Poles actually did this and nearly exterminated a panzer division in 1939. Nobody expected supposedly-defeated Poles to sneak into a town occupied by Germans at 9:30 at night and then begin stabbing the Germans in their beds… Did I mess up?”

Who and when? You are probably thinking about 49th Hutsul Rifle Regiment:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/49th_Hutsul_Rifle_Regiment

but then: it didn’t attack panzer division, but part of SS-Standarte Germania (which was Regiment) and this was September 15/16 when outcome of war in Poland was not yet known.

1. There were other cases, too, although on a much smaller scale. Not because bayonet was a weapon of choice of the Poles, but as a result of the selected tactics. They were ordered before the attack to empty their rifles’ magazines, to make sure that the stealth of the attack would not be compromised by some over-anxious (and whou would not be over-anxious)attacker.

2. The spike-type bayonet, ridiculed in some of the entries, was actually mandated by one of the conventions which were to make the business of killing at war more humane. The wound inflicted in that way was to make easier the flow of blood, preventing developing internal hemorrhages. Actually the only two (to my best nowledge) coutries that abided by the ruling were France (with Lebel) and Russia/Soviet Union as late as 1944 with the 1944 Mosin Carbine.

I do not have any written support for this – I heard this during a lecture on the military law, from a colonel who seemed to know his business.

Regards,

Andrzej

I personally would like to see MORE of your blogs on various bayonets. Yes, and even slings.

Euro,

Being likely the only guy in the room with somewhat real experience in various forms on a knife fighting ( to include the bayonet) I can say the absolute worst thing to do is turn your back and try to run away. Instead your task is to get closer, inside the arc of his point where you stand a real chance of doing damage to an opponent that has now found his too-long weapon is useless. Worse, it’s an emcumbrance and not even good as a club. And to make things even worse for them, they don’t want to let the encumbrance go. Just imagine the depredations one could do with bare hands to a defenseless opponent who can’t even use his hands.

I could go on, but you can’t count on support if bayonets are in use…your buddies will be dealing with their own problems…and I assume you’re joking about finding a convenient tree to hide behind.

Sort of reminds me of my Dad, on the Aleutian campaign against the Japanese. It seems they were all promised “…there was a girl behind every tree….”

Except, when they got there, there wasn’t any trees. :):):)

Whether running away is an option depends on the distance you see him coming. If he’s right or almost on top of you, it really is not feasible like you wrote, because he will just stab you on the back.

The thing about a tree was only half-joking. You can use an obstruction like that as a shield by keeping it between you and the opponent. It will partly negate his advantage in reach just like an actual shield would. Literally hiding behind a tree usually isn’t possible, though…

Would tossing a boot, a rock, or a stick grenade into the attacker’s face get him to STOP charging?

Possibly, but only if you have time to get them somewhere. A rock (or stone, if you British 😉 ) would be the best option, but you would still have to find one big enough and hit some vulnerable point, preferably face or throat with a powerful throw. Collar bones, kneecaps and of course the ever-popular genital area might work as well, but they are even smaller targets.

A hand grenade… using one as a throwing weapon could work as well. A boot would not be practical (do you have an extra on your person?) and a stick would be too light in most cases.

“… knife fighting ( to include the bayonet) I can say the absolute worst thing to do is turn your back and try to run away. ”

While I have little doubt that soldiers in boot camp are probably taught this as absolute fact (and for obvious reasons) but i’ve got to wonder the likelihood of being out-sprinted by someone who is carrying a 10 pound rifle.

Last time I checked, you may out-sprint the rifleman but his friends may still be able to shoot you if you’re STUPID enough to run away in a straight line! And the only way you’re going to get into a fight with a bayonet-happy rifleman is if you’re actually part of a team trying to kill him!

I’d be more concerned about the contents of the rifle’s chamber and magazine. Nobody outruns little bits of metal moving at Mach 2 or 3.

cheers

eon

Precisely the point. You may outrun the gunman, but only some superheroes outrun bullets. And as you said before, swords can’t chop through gun barrels unless the user is freakishly strong and unless the sword in question has very good structural integrity and strength. In fact, if one were to try it, more likely the rifle would be rendered useless with the sword stuck in the stock or both the rifle and the sword would shatter.

The sword would bend and become blunt, the gun barrel would just have small dents in it and probably remain in working condition, assuming the sword would be swung by a man rather than a machine. If a machine would swing it with great speed and force, the blade might shatter or bend very badly, but I doubt it would cut very deep into the gun barrel even in that case.

Myth busters tested that one with cutting contest quality katanas , an M1919 barrel and a sword swinging robot. Even ramped up to superhero strength they mostly ruined sword blades.

When I was doing infantry basic training in 1969, we were given fairly intensive bayonet training at times (Australian Army, using SLR (7.62mm FAL)). I remember it as the most exhausting physical exercise I have ever experienced, since they ran us in the heat until we dropped. However, before this started, a couple of drill instructors stood in front of our unit and announced to us that they would show us how to win a bayonet duel. They then squared off with bayonets fixed, much to our amusement. Then there was a loud bang as one fired his rifle (blank) at the other. “That’s how you win a bayonet fight” he said. History shows that Australian and NZ troops favoured the bayonet in WW1, and to some extent in WW2 (the Battle of 42nd Street on Crete is a good example), but I am sure it is not so much these days.

Poor Pulio bastards! I can’t imagine running up hill through that beaten terrain, with that much rifle and bayonet, with that much heavy wool garb and kit; against an entrenched enemy…

Reading all the comments on bayonetts reminded of a conversation I had with a WW2 Marine vet at a army surplus store I used to work at. We had a jungle hammock hanging up on display in the store. He looked at the hammock and then looked at me with a look of disdain on his face and said “You couldn’t pay me to sleep in one of those #@$&!” I asked him why and he told me that he had been at Guadalcanal, guarding Henderson field. He told me that they had been there for some time. Everyone was sick and they were supplied badly. Finally the army sent in a antiaircraft section to protect the airfield from Japanese air raids. He said the army guys laughed at the fact that the marines were sleeping on the ground with all the bugs and they showed off their new bug proof jungle hammocks. He said that night the Japanese infiltrated the line and caught the AA detachment asleep in their hammocks. They started bayoneting the guys in the hammocks. The guys in the hammocks couldn’t get out of them fast enough and he said many died. The marines sleeping on the ground were able to fend off the attack. A interesting story, now every time I see a jungle hammock this old marines tale runs through my head.

Bayonets may be fearsome, but their use in confined space (once enemy trench was reached) is limited. According to what I remember from my late grandfather, on Italian front it was unthinkable to live and survive without “storm-knife”. It was basically a butchers knife with blade 8-9 inch long.

Their use in open country warfare was pretty dubious, too, as rifle fire generally decided the issue long before it got to “Rosalie range”.

Going back to the American Civil War, while movies portray it as a bayonet-fighting fracas of enormous proportions, actual medical records show that bayonet wounds were extremely rare. As Jack Coggins relates in Arms and Equipment of the Civil War, bayonet “kills” were so rare they tended to get mentioned in dispatches. The supposed bayoneting of Union troops in their tents at First Bull Run by Jackson’s troops was determined to be a myth; the official reports stated that not only were no men “spitted in their tents” as the news reports said, nobody got skewered anywhere else in the engagement, either.

As for the “bayonet charge” of Chamberlain’s Maine Volunteers down Little Round Top at Gettysburg, it was actually an advance downhill at a walk, and the Confederates broke and either ran or surrendered when they saw them coming.

Which was just as well for the Maines. The reason they did it that way was that they were completely out of ammunition.

Chamberlain later said that he simply had run out of ideas at that point, and that it was strictly a case of going down the hill being better than waiting on top for whatever the Confederates decided to do next.

So much for Hollywood.

cheers

eon

We must remember that bayonets were invented go replace pikes, which in the 17th century were becoming increasingly dead weight on battlefield. The primary function of the 17th century pikemen was to shield the musketeers from cavalry charges. Pikemen vs. any other kind of infantrymen combat was rare. Pikeblock vs. pikeblock was potentially very costly for both sides and therefore rare. Unlike earlier historical spear-wielding footmen the pikemen did not have shields, because the 17th century pikes were two-handed weapons. Pikemen vs. musketeers was also fairly rare, since at longer ranges the attacking pikemen would take horrendous casualties from musket fire without any means to retaliate, and of course using them that way would leave the musketeers vulnerable to cavalry.

To conclude: because bayonets replaced pikes, they were even at the beginning not terribly important for pure infantry combat, as their main function was to counter cavalry.

So fast forward to US civil war: the rifled muskets increased the effective range of musket fire considerably. So, in order to get to bayonetting range the attacker had to walk through a lot of fire. On the other hand he was also capable of returning fire. So, in most cases one side would break before bayonets were used. The side with some protection like a stone wall and later trenches had a big advantage.

Civil War ranged weapons heavily favored the defense over the offense, simply because it’s a real PITA to reload a muzzle-loading rifle-musket on the move. You either have to stop, or try to reload “at trail”, which either brings you to a halt or at least slows you down a lot. Both trap you in the defenders’ kill box.

This as why Pickett’s “Charge” at Gettysburg failed, among other things. The Union line was standing still behind a breastwork they’d had time to throw up, and each man just had to worry about loading and firing by the numbers. Pickett’s men had to try to shoot and reload at the walk, quick step, double-quick step, and then into the full charge. Across almost 3/4 mile of open pasture.

While even a .58 rifle musket isn’t that accurate beyond about 400 yards, with a mass of men moving in lines and clumps on one side, and a double line of men shooting by half-company and individual on the other, the law of averages states that the guys in the moving mass are going to get mauled. That much lead flying is bound to hit something. And return fire is going to be sporadic at best.

(The Turner movie “Gettysburg” gives the Confederates a little too much volume of fire in that sequence; reduce what it showed by about 50% and you’re probably closer to the actual level of fire they were generating.)

Add in the failed artillery prep (fuzes burned too long, and the spherical case that was supposed to savage the Union line only succeeded in rousting the Union 12-pounders out of the woods behind the line ahead of schedule, getting them up to the line and in position almost half-an-hour early, and bloodying them just enough to seriously piss them off), and about the best that could be said of the entire maneuver was that it was one of the biggest blunders of the entire war.

Plevna in 1877 was an example of the same thing with single-shot breechloaders in the advance and full-on repeaters (Winchesters) on defense. It’s interesting to speculate how history might have been different if in each case, the assaulters had been armed with rapid-fire repeaters.

cheers

eon

The Blackfive blog had a report of the South Argyle Highlanders mounting a successful bayonet charge against a numerically superior enemy ambush.

Was that the Battle of Danny Boy? As I recall, the ambushing locals were taught that Americans and all westerners were worthless cowards who run away when assaulted by brave jihadis. When the Commonwealth troops got personal with bayonets, the Mahdi militia ran away screaming “mommy.”

Although I was going to say it’s safe to assume that not a single Mahdist was skewered at Danny Boy as none were present, I was amazed to discover that a Mahdi claimant does indeed figure into the Iraq War story- in January 2007, a presumptive Madhi and his believers staged what may or may not have been an abortive uprising in the vicinity of Najaf, and fought it out for two days with Iraqi and Coalition forces. Details are scarce and somewhat contradictory (an American officer allegedly describes the situation on the ground as ‘bizarre’); it’s certainly the strangest episode of the war I’d never heard of.

However, to return: don’t conflate a Mahdist with your garden variety Jihad John; the latter thinks the former is a heretic of the worst sort. He might even be inclined to stick him with a bayonet.

Re the comments above about ANZACs and bayonets etc – History shows that Australian and New Zealand troops favoured the bayonet in WW1, and to some extent also in WW2, especially in North Africa and Crete (where the Battle of 42nd Street is an example). However, in New Guinea, I don’t think the same could be said. A possible exception might be the Battle of Eora Creek. Also, I have never come across anything to indicate that raids on Japanese positions with knives or bayonets were common. What was common was the very effective use of Thompsons and Brens in ambushing the Japanese as they advanced along the Kokoda track. Also, while the Australian troops were heavily outnumbered by the Japanese for the first few weeks of the Kokoda campaign, this was eventually rectified, and the Japanese were generally outnumbered and outgunned thereafter. At Milne Bay the Japanese were heavily outnumbered, and defeated in savage fighting.

When I was doing infantry basic training in 1969 (Australian Army, with 7.62mm SLR (FAL) ) we had quite a bit of bayonet training. I remember one occasion as the most exhausting physical exercise I have ever experienced, since they pushed us in the heat until we dropped. Before this, we were given a demonstration by a couple of drill instructors in ‘how to win a bayonet fight’. The two of them squared off with bayonets fixed, much to our amusement. After a brief period of ‘duelling’ there was a loud bang as one of them fired his rifle (blank) at the other. He then said ‘that’s how it is done’.

Cherndog, I don’t recall all he details of the account. It was years ago and memory fades with time.

Blackfive also had a report of an El Salvadoran patrol that was ambushed and overran. The Sgt. leading the patrol saw some of his men being dragged off, and being out of ammo, he pulled his fighting knife and attacked. The Marine relief unit said it looked like someone had hosed the place down with blood. None of the Sgt’s men were missing. The Marine unit made the Sgt an honorary Marine because anyone badass enough to bring a knife to a gunfight and win had to be a Marine.

Made a good spear for a fight. That art is almost dead.