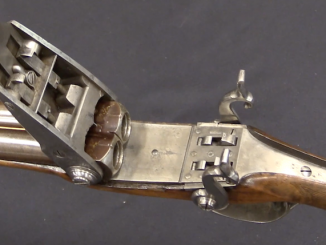

Harmonica guns were a short-lived type of firearm that was developed in an effort to have reliable repeating weapons prior to the the modern centerfire cartridge. They were made in both muzzleloading and cartridge varieties, and one notable (and reknowned) American maker of such guns was Jonathan Browning, father of John Moses Browning. These two harmonica pistols (a short 7mm one and a larger 9mm one with a fixed barrel) was made by a man named Jarre in France (also a noted manufacturer), and both use pinfire cartridges. In addition, while early harmonica guns had to be manually indexed for each shot, these two automatically advance their slides when their triggers are pulled. Both are available for sale at the upcoming Rock Island Auction…

Related Articles

Semiauto pistol

Le Français .32ACP Pistol (Video)

The Le Français was a staple of Manufrance production, being first designed in 1912 and produced until the late 1960s. This example is in .32ACP caliber, which was only made for the commercial market in […]

Heavy MGs

Heavy Machine Guns of the Western Front, WWI

I have been really enjoying The Great War series on YouTube (a rolling weekly account of what happened in WWI this week 100 years ago), so I figured I ought to take advantage of an opportunity […]

Shotgun

Samuel Pauly Invents the Cartridge in 1812

https://youtu.be/BC7awTeuqRU This Pauly shotgun is lot #1346 at Morphy’s April 2019 auction. Samuel Johannes Pauli was born outside Bern, Switzerland in 1766, and became an engineer of wide interests. Among them were bridge design, passenger-carrying […]

How would you normally carry these pistols? Did any holsters exist for them?

They look like they might be intended as pocket pistols, with the chamber carried separately from the rest of the pistol (or hanging off the end, in the case of the smaller example here). You would then assemble the chambers to the pistol only when you thought you needed it.

The problem with that, of course, is exactly what the footpad(s) who accosted you would be getting up to while you were fumbling with one of these things, trying to assemble it. Probably in the dark.

There’s a reason most Continental pinfire revolvers were double-action. They were intended for self-defense at “sweat and bad breath” range, where precise shooting wasn’t nearly as important as fast shooting.

Even with a DA trigger, the harmonica pistol flunks the test. In modern terms, think of carrying a Beretta M9 or Glock 17 9mm completely empty, with the magazine in another pocket, and having to slam the magazine in, then do a tap-rack-BANG to fire.

Best guess is that by that time, you’ve probably already been dead for about four seconds.

Even a single-action revolver is faster than a DA harmonica gun in CQB.

Incidentally, AFAIK, most if not all of Jonathan Browning’s “harmonica” arms were rifles and shotguns, intended for sporting use. He also made revolving rifles and shotguns. They did not need to be “fast-reaction” arms, as sporting arms are brought into action relatively slowly and deliberately. After all, one does not go wing-shooting and attempt to load the double gun just as the quail flushes.

All of the above were percussion, and even with his careful workmanship, the harmonica arms were just as vulnerable to multiple discharges as percussion revolver-type arms were. With the attendant risk of injury to the shooter’s off hand and forearm.

Like the percussion revolving longarm, the harmonica gun was a dead-end development. In fact, it was basically “out-evolved” before it ever arrived on the scene.

cheers

eon

During firing this weapon the center-of-gravity point go from right to left. I am wondering how it affects accuracy?

I also think that the harmonica gun were made rather to be curiosity than utility firearm, like Chaineux 20-shot pin-fire revolver – it looks interesting and can fire more times than then-standard cap&ball revolver, but is awkward to normal use.

Browning’s patent sliding breech anyone? Browning senior that is

What is the purpose of the plunger looking thing on the Browning pistol? The thing sticking up just above the web of the hand?

I figured that out after the video was done – is an ejector rod threaded into the grip.You would unscrew it when needed to empty out the harmonica bar for reloading.

Excellent explanation, as ever, Ian.

I’ve sometimes wondered if those old 7mm and 9mm pinfire pistols could actually deal a fatal wound, given their pitiful charge of blackpowder. Does anyone have any accounts of any deaths attributed to one? I did find one tragic case of an accidental shooting in the UK about 10-15 years ago, but I believe that was with a heftier 12mm pinfire revolver. (All a bit morbid, I know.) If anyone has access to some reproduction pinfire ammo and some properly calibrated ballistics gelatin, I for one would be intrigued to see the results. (And the same goes for a lot of those old pipsqueak pistol rounds in “Cartridges of the World” such as .320 British revolver and .41 Rimfire.) I’ve seen the YouTube videos of pinfire revolvers fired into fibreboard, but, of course, there’s a good reason why they use gelatin nowadays. 😉

Cheers all.

According to The Illustrated Book of Guns (Salamander, 2002), the 7mm and 9mm pinfires had roughly the same ballistics as the percussion and rimfire loads of their day, i.e. muzzle velocities ranging from about 400-450 FPS for short-barreled arms like the pinfire pepperbox “fist pistols” (including the Dolne and Delhaxhe “Apache” knuckle-duster guns), up to the 600-700 FPS range for revolvers with 4 inch or longer barrels.

Assuming similar bullet weights (about 50 to 60 grains for the 7mm and about 80 to 150 grains for the 9mm, the heavier weight in each case being a conical bullet), the final energy result should have been about 25 FPE for the 7mm “pepperbox”, about 50 FPE for a 7mm revolver, about 40 FPE for a 9mm “fist gun”, and about 100 FPE for a 9mm revolver. Longer-barreled revolvers, as with their American counterparts like the Colt 1851 .36, could probably produce about 125 to 150 FPE with a conical bullet of about 150 grains.

Ballistically, none of the above were particular impressive compared to even a modern .22 rimfire. But all of them were capable of penetration to the vital organs, although a head shot would have been problematic.

The real problem of course was that in pistol-length barrels it really wasn’t practical to get any bullet going much faster than about 700 FPS. This was the reason that big bores (.44 and up) became popular in the post-Civil War era. If you couldn’t get the bullet to go faster, the only way to increase its energy, and thus its killing power, was to increase its mass. A 250-grain bullet at 700FPS hits with 270 FPE. One traveling at 900 FPS (Colt .45 M1873, cavalry 7.5″ barrel) delivers 450 FPE at the muzzle.

It took the advent of smokeless powder to make velocity the ruling factor in hitting power. Before that, it was projectile mass that was the key.

But as a rule, if the bullet could penetrate to the vitals, the recipient was in bad trouble, especially considering the medical knowledge of the day. Today it would be defined as “medical malpractice” for the most part.

Few men shot with the pre-1870 handguns died on the spot when shot, even in the American West. But then again, before about 1900, few survived more than a few hours after being shot, either.

cheers

eon

“it was projectile mass that was the key”

But bigger mass can be also achieved by using longer bullet in smaller caliber. For example: .38 S&W has .361 diameter, 200 grain bullet adopted by British Forces as a 38/200. Why using the larger-bore projectile was more popular than small-bore long projectile?

“But as a rule, if the bullet could penetrate to the vitals, the recipient was in bad trouble, especially considering the medical knowledge of the day.”

Also the outside-lubricated lead bullets has bigger chance to cause the infection than modern inside-lubricated FMJ bullets. Not to mention than in modern times we have effective antibiotics.

“Why using the larger-bore projectile was more popular than small-bore long projectile?”

I think it was mainly psychology. The single-shot muzzle-loading weapons of the day, even pistols, still had “musket-sized” bores, .54 and up to around .69 or even .75. The “big bore” was still equated with killing power.

The fact is, those old “big bores” weren’t all that powerful, unless you loaded them to the maximum. According to Ian Hogg, the standard service load for the British Model 1802 Long Land Service .75 caliber musket, the version of the “Brown Bess” used at Waterloo, launched a 490-grain round ball at 600 FPS with the standard service load, which works out to about 45 grains of FFFFg in modern terms. This yields about 397 FPE (533j) at the muzzle, with velocity and energy naturally falling off pretty quickly due to air resistance.

The later Enfield .577 rifle musket with a 460-grain bullet and a 100-grain powder charge yielded 1,000 FPS at the muzzle and about 1,100 FPE (1480j). That’s about the ME of the modern-day 5.56 x 45mm NATO round, which is considered an “intermediate” cartridge. (Except for those who call it a “mouse gun”.)

In modern terms, the Brown Bess had about the bore of a 12-gauge shotgun, and the Enfield had about the ore of a 20-gauge. But modern-day shotgun “slug loads” have more KE than the round balls or Minie’ balls of the muzzle-loaders, simply because of their higher velocity.

During the American Civil War, the Spencer repeating rifle was more popular than the more advanced Henry, even though the latter held thirteen rounds in its magazine to the Spencer’s seven. This was partly because the Spencer, while less sophisticated, was probably sturdier (think AK-47 vs. M-16), but a lot of it was the fact that the Henry was a .44 (defined back then as a pistol caliber), while the Spencer was a .52 (not far off the .54 caliber of most pre-war military muzzle-loading arms). In fact, both had about the same muzzle energy, about 600 FPE/800j, and thus were probably about equal in man-killing power out to their maximum effective range of about 200 yards.

In a very real sense, the Spencer and Henry were the “assault rifles” of the American Civil War. The single-shot breechloaders (Sharps, etc.) introduced the concept of firepower as a force multiplier, but the repeaters carried it to its logical conclusion within the limits of the technology base. And they were “intermediate” power weapons by the standards of their day.

The idea that a longer bullet would increase hitting power really only came along with the advent of smokeless powder. And it did so more or less by accident, when it was discovered that such bullets, with cupro-nickel alloy jackets, shot more accurately when fired from rifles at the higher velocities attainable with the new propellants.

The increased wounding effect of a long bullet that flips over at least once inside the recipient’s guts was just a bonus, really. And was still considered inferior to a “traditional” big-bore lead bullet, as the latter tended to make very, very big holes in the hapless target.

cheers

eon

“The “big bore” was still equated with killing power.”

So this was something what is our times called marketing. But using the keyword “big bore” in place of “Magnum”.

“that powerful”

I doubt in “stopping power is directly proportional to kinetic energy”. Defining the stopping power is (and was) very controversial. I prefer momentum (mass of bullet * velocity) if approximate power indicator is necessary.

“And it did so more or less by accident, when it was discovered that such bullets, with cupro-nickel alloy jackets, shot more accurately when fired from rifles at the higher velocities attainable with the new propellants.”

The fact that longer (heavier) bullet is more accurate was known before advent of smokeless powder. In 1880s A. Gould (editor of “Shooting & Fishing” magazine) do accuracy test using then-popular cartridge at a distance of 200 yards. The cartridge were divided into 4 groups. To 1st group (most accurate) belong following cartridges:

32-40-125, 32-40-150, 32-40-165, 38-55-255, 40-83-390.

As you can see the blackpowder cartridge American was used so it denote caliber (inch*100) – powder charge (grains) – bullet mass (grains).

The first 3 loadings are cartridges now called “.32-40 Bullard”, true bullet diameter is .320; the 4th is now called “.38-55 Winchester”, true bullet diameter is .3775; I am not aware about “.40-83-390” cartridge. Has anybody information concerning this cartridge?

Daweo;

I’ve never heard of a .40-83-390, but Sharps had a .40-90-370 in their 2 5/8″ necked case, as opposed to their 2 1/2″ straight-taper case used for the .40-65-330. You could be looking at a “variant” loading of the .40-90-370, possibly chambered in a Remington, Marlin-Ballard, or Maynard rifle.

cheers

eon

This is a note to Rock Island: it would benefit your consignees (i.e. the owners of the guns) to let Ian take them apart, at least a little more. Obviously it is a matter of permission between private parties; a seller must think that Ian’s video will benefit their auction. Of course it will! Why not let him unscrew a few screws and show the guts, as he is most capable of doing? For one thing, he will put it back and you will get a better price on your oddity. For another: you do a favor to anyone who wonders at a capricious or obvious design. It is a matter of record! Why not be the owner who shows a strange detail to the world? No one else could.

The spell-checker has placed an extra k in renown. And yes, there is a hypen in anal-retentive!