The M1915 Howell Automatic Rifle is a conversion of a standard No1 MkIII Lee Enfield rifle into a semiautomatic, through the addition of a gas piston onto the right side of the barrel. Despite its very steampunk appearance, the Howell is actually a quite simple conversion mechanically. The rifle action had not been modified at all, and a curved plate on the end of the gas piston is used to cycle the bolt up, back, forward, and down just as it would be done manually.

The additional metal elements added to the gun are there to prevent the shooter from inadvertently getting their hand or face in the path of the bolt. The crude tubular pistol grip is necessary because the shooter’s hand on the wrist of the stock would normally be in the path of the bolt’s travel. Note that the Parker-Hale bipod on this example is a non-military addition from its time in private ownership.

In addition to these elements, the Howell has been fitted with a 20-round extended magazine to better exploit its rate of fire. However, the Howell was made as a semiautomatic rifle only, and not fully automatic. It was offered to the British military circa 1915, but never put into service. Instead, the British would significantly increase production and deployment of Lewis light machine guns. Howell would offer his conversion in basically the same form to the military again at the onset of World War 2, but was again turned down.

Shooting the Howell was remarkably successful – I had expected it to be very malfunction-prone, but in fact it ran almost completely without fault. In retrospect, I would attribute this to the simplicity of its conversion, which made no changes to the feeding and extraction/ejection elements of the SMLE. The gun was a bit awkward to hold, and the offset sights left one with really no cheek weld at all, but recoil was gentle thanks to the gas systems function and added weight. Quite a remarkable gun, and one I am very glad to have been able to shoot.

The pistol grip angle is similar to the Boys anti tank rifle. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boys_anti-tank_rifle

“crude tubular pistol grip”

Pistol grip was also added in Mannlicher-Yasnikov:

http://www.hungariae.com/Mann95Ru.htm

Very similar, but it seem to be little more ‘cultured’.

Polish conversion of Mannlicher to gas-operated:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1zf-mGMLjoU#t=53s

also features added pistol grip, which like Howell conversion is “reversed” (under angle less than 90°, see link)

Steyr M95 Semiauto Conversion which was discussed here:

https://www.forgottenweapons.com/steyr-m95-semiauto-conversion-video/

also has added pistol grip, although in “proper” direction.

“…and ugly rifle”

I just love this part of comment. It gives me relief if in past I made immodest comment myself. That whip and wiggle threatens to disengage mechanism at any moment during the cycle.

Other than that it seem to work rather smoothly. It pops out bullets and that is name of the game.

It is functional and seems to hold up well considering its age. For that matter, one can be amazed just how effective the belittled Chauchat could become had the magazine NOT been designed to act as a bullet counter and had production standards been much higher…

Why do we have to go on an on about the Chauchat? I think it has been agreed by most historians that that done serious research the CSRG 1915 was a reasonably successful weapon in French and American hands. 250,000 were made and used extensively. It was what it was and both the French and US Army utilized and it was not until the US made the mistake of attempting to quickly adapt it to the US service cartridge as the CSRG 1918 through French manufacturing that was not up to the task, that a bad result occurred. They rushed through the M1917 Enfield, a much less complex design, and even Winchester got it wrong the first go round, fortunately folks were paying attention in the states to make sure that they got it right. Be my guest if you want to compare it to the CSRG 1918 all day long for whatever good you think that would do, but darned that the CSRG 1918 didn’t have a closed in mag that didn’t do a bit of good.

I said that the Chauchat was “belittled,” not “crap.” Haste tends to waste tons of perfectly good resources when bureaucrats get into the mix. This was especially true for the M16, when obstructive and willfully ignorant politicians rushed the guns into service and unwisely cut costs by procuring cheap ammunition (which produced lots of soot) and buying corrosion prone barrels. You can imagine the results. Rushing anything into service without proper testing tends to end badly. Heck, the Chauchat would beat the pants off the MG08/15 in terms of handiness and deployment speed, since the latter is technically an adapted heavy weapon which still needed cooling water. Did I mess up?

Don’t forget, too, that this is a prototype, and there’s plenty of refinement to be done before it could be turned into a workable mass-produced issue rifle.

Great rifle and really great review. One of your best.

What’s the total weight? It really does look heavy.

What about center-of-gravity point? I know that Mannlicher-Yasnikov have problems due to this, but what about that weapon?

I think it has the added advantage of making Ian fire from the right shoulder as his lefty shooting freaks me out. :-}

Once, there were “Trombone Action” .22″ rifles and a M1 Carabin convertion modified from auto to slide action. If so, this one should be the “Oboe Action”

of these convertion genre. Most straight forward adaptation of bolt to auto action rifle ever made. Wish the steampunkt creators were aware of that.

Note that the Bren, ZB26, and other LMGs with top-mounted magazines all have the sights offset to the left, in their case because centerline sights would be useless with the magazine in the middle of everything.

This rifle shows up in the 1972 Petersen Books Guns of the World in the Collector’s Catalog section on p. 208. It is listed and pictured as the “Experimental Conversion of 1918” and notes that it was also known as the “Sword Guard” pattern due to the shape of the cam piece, remarkably like the handguard of a cavalry saber.

The first pattern Charleton SL Rifle, predecessor of the Charleton LMG, is listed at the very top of p. 209, and its internal resemblance to this rifle is noted.

Further back in the book, on 278-79 in the article on Swiss military rifles, a similar conversion of the Schmidt-Rubin Model 11 is shown. It was an easier job as of course the S-R already has a cam path system (being a “phony” straight-pull, i.e. a turnbolt with extra gadgetry to provide the straight bolt-pull), and so only the addition of a gas-piston and return-spring assembly were required.

Frankly, no amount of examples can make this Rube Goldberg setup a particularly good idea. I noticed the wildly inconsistent ejection of the Howell, with a couple of rounds nearly dropping right back into the action.

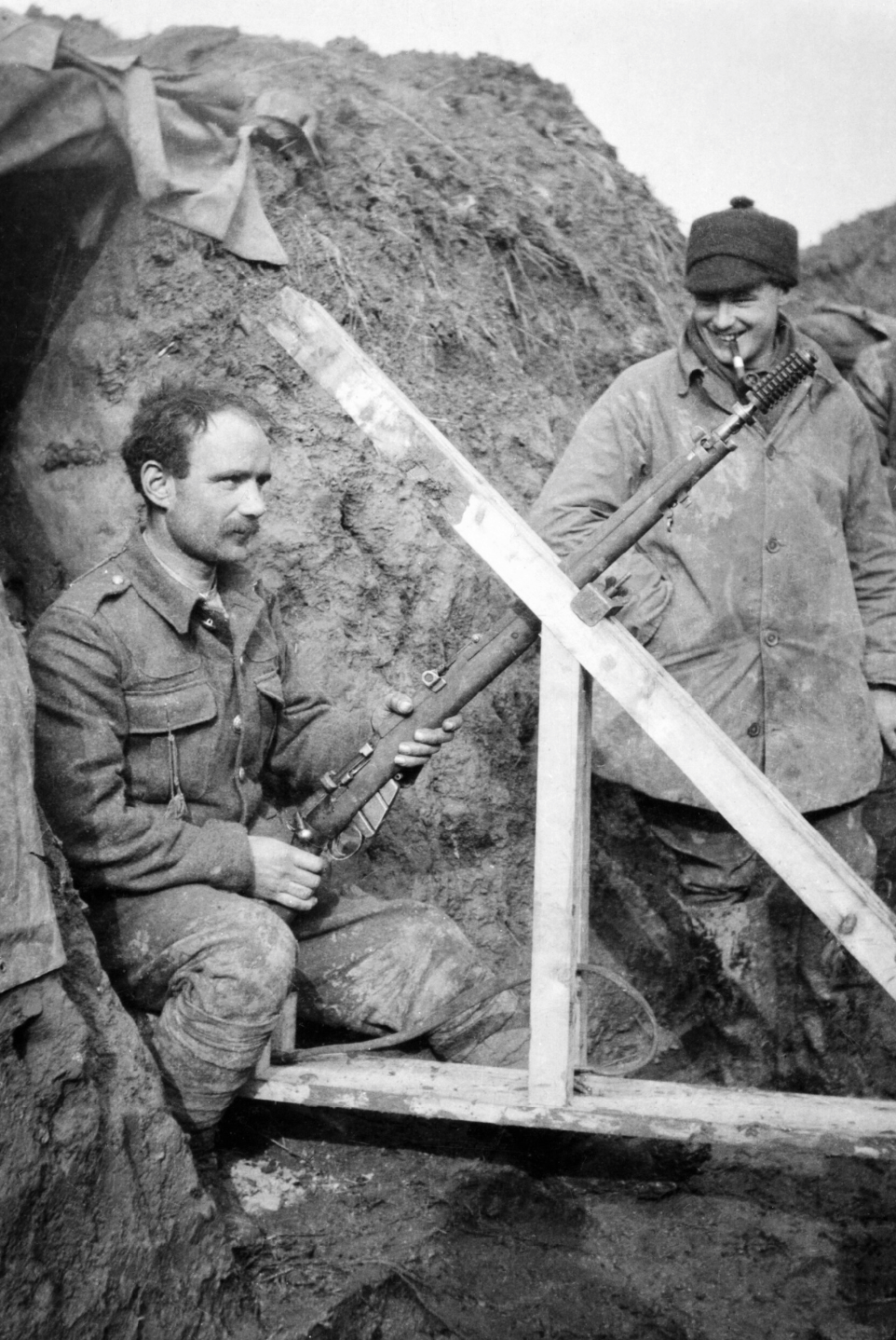

It might work reasonably well in a nice, clean firing range. In a trench in Flanders mud? That would likely be another story entirely. Note that the French self-loading rifles, the St. Etienne M1917 and M1918, had problems with that environment, and they were of a much more sophisticated design than this, with much better protection of the mechanism from “external influences”.

PS- The main use of the Winchester M/07 and M/10 self-loading carbines was in the trenches, not by aviators. They were quickly replaced in aircraft by actual machine guns. In trench raids, the Winchesters’ handiness and relatively high volume of fire at close range were effective enough to influence the Germans to come up with something similar. The result was the Bergmann Muskete, the world’s first true sub-machine gun.

cheers

eon

“The result was the Bergmann Muskete, the world’s first true sub-machine gun”

According http://modernfirearms.net/smg/it/beretta-m191-e.html it is possible that Beretta M1918 should get “first conventional sub-machine gun issued” label

The Beretta was essentially a modification and improvement of the Villar Perosa OVP, which began life in 1914 as a twin-gun mount for flexible mounting on an aircraft, then s a twin-mount LMG for infantry support, mounted on a bipod, with a two-man crew and a cart to haul the ammunition.

The OVP proper was one of the two guns with a conventional trigger, and a rudimentary shoulder stock, but retaining the top-mounted magazine of the twin mount. Plus a cocking “sleeve” that nobody liked because it was good at pinching fingers.

The Beretta substituted a full stock and a proper cocking handle, but retained the top-mounted magazine. More to the point, it was introduced in the fall of 1918, after the Bergmann had been in use by German Sturmtruppen since the spring 1918 German counter-offensives. So most if not all of its “improved” features were probably copied from captured Bergmanns.

I think the Bergmann’s position as the world’s first true SMG remains fairly secure.

😉

cheers

eon

An interesting solution to a problem the Brits did not have in WWI. Fortunately for the Brits they had an outstanding battle rifle. Now, if they didn’t have the Lewis gun to support the SMLE’s…. Also I wonder how this rifle might have functioned in the freezing cold and combat conditions with its basic mechanism exposed or worse, parts that could not be gotten to easily. It only takes one Achilles’ heel to doom a weapon system.

Jeez, how in the world could you get your basic troop to use such a thing? I mean it threatens to scoop an eyeball out if not your whole face off with every pull of the trigger.

It appears to work much like the parachute MK1… not so difficult to get them to try once, damn near impossible to try a second time.

This is as absurd as creating a drone aircraft by building a robot to fly a conventional aircraft. Rube Goldberg approved

Too bad we didn’t get to see the malfunctions in slow motion. From the description, it sounds as if the cocking handle managed to bind in the cam?

I suspect the advantages of the SMLE action that make it so fast and smooth contributed to the reliability of these types of SMLE conversions. Short bolt turn, short bolt throw, not trying to cock while extracting (and if you have enough “Ooomph!” to extract a fired case cleanly, the return run of teh spring will certainly be enough to close and cock the action), etc.

is it possible to find any more information about Howell himself? i’ve gone through every link i can find about this gun and the only further detail i could find (without a source) was that his initials were N. Howell