In the world of small arms engineering, one of the most exciting developments of World War II was the German work on roller locking and roller-delayed blowback actions. British, French, and Soviet armies were jumping all over each other to take custody of German engineers and prototypes, and these roller guns were particularly interesting to everyone. We know that the French did a lot of work on the concept with the aid of Karl Maier and Ludwig Vorgrimler, and the Spanish eventually worked with Vorgrimler to produce the CETME rifle. The British also worked with roller locking systems and developed the EM1 rifle as the outcome. But what about the US?

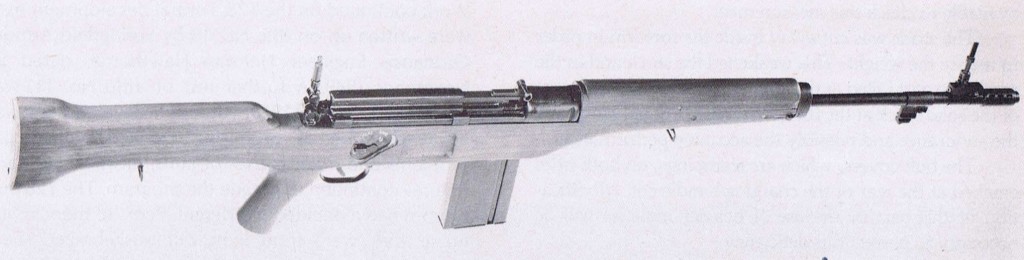

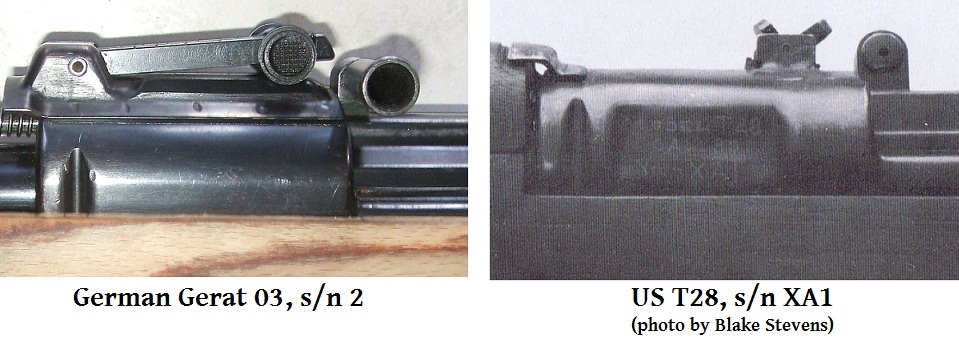

As it turns out, the R&D division at Springfield Armory did get its feet wet in the roller locking pool. Captured prototypes had been sent back to Springfield, and in late 1945 an engineer named Cyril Moore took on the project of developing a roller locked, gas operated rifle in the new T65 cartridge (which would eventually become the 7.62mm NATO). Moore’s design closely followed the German Gerat 03, using a gas piston mounted atop the barrel, a stamped sheet metal receiver (and other parts), and very similar bolt and bolt carrier. Note the similarities on the front ends of the receivers:

Moore received pretty minimal funding and support for the project, as the T25 in parallel development was the rifle expected to be the replacement for the M1. Still, it was important to at least pay lip service to alternatives like the T28. After several years of work, Moore had a number of completed prototype guns, and the first test of them was run from September 1948 through January 1949 at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, using guns number 5 and 8. It is important to note that these guns were roller locked, and operated via short stroke gas piston – not a delayed blowback system like the final German wartime iteration of the design.

The report issued after the testing was complete is mixed, noting several areas where the T28 was well liked as well as a number of deficiencies. Overall, it is clear that the rifle suffered from insufficient study of the German guns, and insufficient development. First off, the things the Army like about the T28:

- Simplicity of field stripping – it could be disassembled and reassembled more quickly than the M1 (although detail stripping it was a real chore)

- Stock design – the high stock used on the T28 helped control muzzle climb and prevented issues of heat distortion of sight picture

- Accuracy – the T28 had a longer sight radius than the M1, and was found more accurate when using equivalent quality ammunition

- Gas port location – the T28 could be field stripped without removing the stock, thus allowing more solid bedding and better accuracy

Sounds like a pretty good review, until we get to the problems:

- The 20-round magazine interfered with proper handling of the rifle

- The T28 occasionally slamfired, as the firing pin spring did not hold back the firing pin strongly enough

- Ironically, also failures to strike primers hard enough to fire

- Numerous failures to extract and broken extractors

- Burring and dimpling of the roller locking components (suggesting improper geometry and hardening)

- Receivers breaking, loosening on the barrel extensions, and pin holes enlarging

Put together, the problems encountered in testing tell a pretty clear story to anyone familiar with the Gerat 03 and Gerat 06. The receiver breakage and loosening indicates a lack of skill and experience with complex stampings, which is not surprising. This was an area of German expertise, and not something Springfield Armory had much practical knowledge of. If the rifle had been considered a priority, this expertise would have been built through practice, much as the Russians developed it through the work done to mass produce the AK around this same time.

A second test was conducted on prototype #11 (see photo above) in October 1950, but many of the same problems persisted. Considering how little time and support were available to Earle Harvey for the T25 – which was considered the important rifle in development – it is very likely that Moore could have rectified many of these problems with more time, but instead the project was dropped by the end of 1950. Army Ordnance at the time was not particularly interested in new ideas, and the T28 project was pretty much doomed to failure from its very beginning.

The irony is that Springfield Armory had Mauser’s Otto von Lossnitzer working for them. However, he was tasked with revolver cannon development, which ultimately led to the 20mm M39. In his autobiography, Col. Roy Rayle pointed out that during the 1950s, most of Springfield’s R&D funding for small arms had been provided by the USAF.

according to this Maier also worked at springfield armory…

http://ww2.rediscov.com/spring/VFPCGI.exe?IDCFile=/spring/DETAILS.IDC,SPECIFIC=10237,DATABASE=objects,

“The man responsible for the original concept was Dr. Karl Maier, a Mauser mathematical physicist. After the war Dr. Maier was captured by the Americans and eventually came to the United States as part of ‘Project Paperclip,’ a program designed to keep German scientists out of the hands of the Russians. In fact, Dr. Maier spent many years working at the Springfield Armory before becoming an independent firearms consultant. Today, Dr. Maier is enjoying a quiet retirement in his native Germany.”

I had totally missed that. A quick search shows that Springfield had Maier working on different small arms operating systems. Rayle wrote that Maier had already left Springfield for private industry by the time that Rayle was transferred there. In contrast, Lossnitzer stayed on until Springfield’s closure.

I just discovered that Karl Maier and Stefan K. Janson ended up working together at Winchester on projects such as the Model 100 semi-auto rifle. That had to be awkward at times, but then this was the same company that had previously kept Marsh Williams and Mel Johnson on the payroll without bloodshed.

An interesting piece of information that helps flesh out the history of the T28 — thanks!

FW: “First of all, it appears that Moore did not copy the chamber fluting used by the German guns to allow effective extraction.”

It was roller *locked*, but *gas operated*. It wasn’t delayed blow-back. Why would it need a fluted chamber? The cartridge wouldn’t have needed to move under high pressure. Was it a matter of the cartridge sticking in the chamber after unlocking?

FW: “The receiver breakage and loosening indicates a lack of skill and experience with complex stampings, which (was) … not something Springfield Armory had much practical knowledge of. If the rifle had been considered a priority, this expertise would have been built through practice”.

They could have brought experts in from the automotive industry. While automotive engineers and tool and die designers may not be experts in firearms, there would be very little they would not have known about complex stampings, welding, and riveting. By far the biggest market for stampings is automotive parts, so that is the first place where you would look for expertise.

Unlike the USA, the Russians didn’t have a big automotive or appliance industry at the time, so they wouldn’t have had the same pool of experienced people to draw from.

FW: “the T28 could be field stripped without removing the stock, thus allowing more solid bedding and better accuracy”.

I’m rather surprised at the relatively conservative stock design. Both examples in the photos have large, one piece wooden stocks. One of the really notable things about the German MP-43/Stg 44 (and related rifles) was that the traditional wooden furniture was reduced to a few smaller, simpler pieces leaving the receiver completely exposed. That would probably make them much easier to manufacture and assemble, and completely eliminate the issues associated with trying to precisely fit a large lump of metal inside a large piece of wood.

Whoops – you are correct about the extraction (I’ve edited my post to take that bit out). I was thinking delayed blowback – so now I’m not sure what exactly would have been causing the extraction problems. Given the experimental nature of the gun (and cartridge, many lots of which often had widely varying pressures), it could have been any number of things.

As for stamping, they certainly could have done it well if there had been an incentive to. In addition to automotive experience, they had von Lossniter and Maier hanging around (as Daniel and duchamp pointed out) – they just didn’t make use of them for an infantry rifle.

Proper timing is essential in the operation of a roller locked firearm action. Roller locking lacks the slow primary / fast secondary extraction phases inherent in turnbolt actions, so the bolt withdrawl has to be carefully timed to occur only after internal pressure has dropped, unless you have ‘floated’ the cartridge case with a fluted chamber. Otherwise, you rip rims off the cartridge cases and experience very high stresses in the extractor.

The photo of the T28 shows a gas port well behind the muzzle of the rifle. The bolt head almost certainly was driven into motion by the gas system before chamber pressure had dropped to a reasonable level for extraction in a roller locked system, say 1,500 psi [10 MPa]. This appears to be the reason that most automatic weapons designers choose turnbolt locking over roller locking.

Firearms designers around the world seem to rely on mechanical fastening, rather than welding to hold their components together. Only H&K has made extensive use of welding in firearms construction. Designers seem to be uncomfortable with the distortion and heat treatment issues which arise from welding, but other industries – notably the oil patch – have mastered these techniques for many years. Properly executed, welding could reduce construction costs and improve durability of a lot of steel firearms components, such as the T28 receiver.

It’s interesting that the list of problems and negative comments by the Army evaluators centered primarily around durability and tolerance issues, which could have been rectified relatively easily with the application of available manufacturing technology. On the other hand, the evaluators’ positive comments nearly all highlighted the T28’s numerous design advantages.

Based on the above-mentioned information, plus the obvious lack of funding and narrow-minded inability to look at applicable manufacturing technology outside the immediate military arena, I cannot help but think that this was yet another very sound design that had enormous developmental potential, but which was needlessly squandered by the Army’s Ordnance Board in their infinite wisdom.

To that effect, I am very much in agreement with MG’s and Ian’s comments.

T28 while being a gas operated system, I’d assume would have two-piece action – meaning bolt and bolt carrier. With such design the desired amount of idle run (dwell) can be built into. From what I read it is not exactly clear. Could you clarify please?

Yes, the T28 had a bolt and carrier just like the Gerat 03 (for a better look at this system, check out the Gerat 03 video we did). So it would have been fairly simple to manipulate the gas port size/location and the bolt carrier weight and unlocking delay time to get the system running smoothly. There just wasn’t the time put into the project to do it.

Roller type lock pieces on either recoil or gas

operated firearms gets the advantage of using only

one camming device for locking process since

unlocking stage occurs via cam surfaces built in the

roller recess. They, also spread stress through

larger area than other types but require more

precise crafted parts and joining workmanship.

On delayed blowback operation, roller lockers, once

got transmitted the backward thrust from breechbolt,

start to roll from direct upright to backward in a

curved direction, cause very little direct backward

motion over the breechbolt during the highest chamber

pressure within a few thousant of miliseconds but gaın

speed approaching to the end of leaving their cuts.

Since the case begins to go backward when the pressure

is on highest level, ıt should be kept in floatıng

mode and flutes within the chamber extending to just

forward of shell stop shoulder provide needed counter

pressure at outside the shell for positive extraction.

One of the most recent and compact roller locking

applications were on the Vz 52 pistol in locked breech

type, and on Korriphila pistol on delayed blowback

kind.

Vz.52 pistol is kind of strange bird since it uses recoil to unlock its action. I happen to have one so I got quite familiar with it. As you may read elsewhere it was originally designed for 9mm Para, but for 7.62mm Tokarev its lockup is rather inadequate.

Quite frankly, regarding all of those theories on speed of action opening with rollers, I believe this is rather dicy perception. The pressure is highhest when nothing is moving yet and than everything, out of sudden is supposed to happen. Rather tricky for serious and practical considerations. I realize these are all transient stages and are hapening in tenses of milliseconds. On ballance we can see that roller locking is on its way out and probably rightly so. FW is doing great job in putting spotlights on them.

One of the most successfull machinegun ever made, German MG42/59 was also

in that kind of strange birds using recoil to unlock the roller locked action.

However, ıt had a “Recoil Booster” getting used of gas pressure of muzzle blast

for increasing the speed of recoiling parts to reach a RPM nearly doubling over the

existing rapid of that time. That gun was also the cause of developing the “Cold

Hammer Forged Rifling” process obtaining more durable barrels to catch that speed.

Vz 52 was a direct derivation of that gun’s action.

Other “Roller Using” most successfull firearm was G3 which remaining in the class

of “Roller Delay” actions in which rollers were served not to lock, but to slow the

brechbolt separation from barrel during the firing.

Hi, Denny :

What has been your overall personal experience with the vz.52 pistol? I’d love to hear your personal viewpoint about it as a user since I’ve been thinking of getting one myself. All the professional and historical reviews I have read seem to rate it very highly, and your comments about the marginal lockup for the Tokarev 7.62mm x 25 cartridge are interesting.

Thanks,

Earl

there is one strong advantage of recoil operation systems over most gas systems in general-that it’s easier to free float the barrel to obtain match grade accuracy- a classic example is the H&K PSG1, probably the most accurate full power production automatic rifle sold.

target bolt actions are usually free floating barrel arrangements for this good reason and why no sniper rifle will have a bayonet on it.

as an alternative, it might be possible to design a gas operation system which allows the barrel to completely free float along the middle, supporting only the very end of the muzzle slip fit into a rigidly jacketed trunnion like the mg34 and mg42 ,where gas can be tapped off between the end of the muzzle and a chamber within the muzzle brake/booster.

this full length jacket (i assume ventilated)would add to the weight but could add other benefits to the design.

true that gas operated designs usually generate less felt recoil than recoil operations and they can allow some user adjustment, but the most effective setup is the kalashnikov employing full stroke pistons with unified piston and carrier assemblies.these yield a very positive ratio of carrier to bolt head weight so action cycling is strong enough to overcome a great deal of carbon and environmental fouling.

however AK derivatives typically place the gas manifold near the middle of the barrel,which in combination with the flimsy/flexing open receiver rails(AKM)result in pedestrian accuracy at best-relegating the design to mostly fire suppression and close quarters to intermediate ranges, which is fine for a general issue assault rifle but not offering “growth” to sniper range mission tailoring like the HK 7.62 nato system.