Today we are taking an original Sten MkII(S) out to the range – something I am excited to be able to do! The suppressor on this Sten is all original, and about 80 years old…and I’m very curious to see how effective it really is.

Related Articles

Antiques

Perdition to Conspirators! Magnificent 14-Barrel Flintlock

Colonel Thomas Thornton was a wealthy and somewhat flamboyant character in England in the late 18th and early 19th century. He commanded a militia unit with which he had some disagreement, and which mutinied against […]

Video

WWI Trench Hand Weapons

Karl and I recently did some work with a wide selection of hand weapons from WWI (some original, some reproductions) for a video in collaboration with the excellent YouTube channel The Great War. Have a […]

Commentary

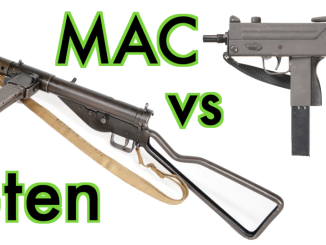

Sten MkII vs Ingram M10/9 (w/ John Keene)

If you had to pick one, would you take a Sten MkII or an Ingram M10/9? This applies specifically to the guns in their original factory configurations; no Lage products allowed! It’s hard to come […]

stupid quiet with the sub rounds. what a dream job!

i would think sustained auto would cause the can to fail catastrophically.

One round mag dump! Excellent

This!

I wonder if/where/who could do a test of making suppressors using just washers and wire mesh. I know here in the USA the legal issue would be a bit of challenge (but not always insurmountable) but maybe in another country where suppressors are less of a legal hassle?

My olde gunne nerd impression was that STENs were made in parabellum in part to make use of the vast supplies of ammunition captured from the Italians in Ethiopia and North Africa. But that would be feeble Glisenti 9mm. I suppose any special troops issued these suppressed guns would have access to consistent ammo. What was British 9mm spec?

This is a tale which is often told about the origins of the Sten, but the timing simply doesn’t line up. The first Sten prototype was made at around the same time as Operation Compass was just kicking off in North Africa, so unless the designers had time machine they couldn’t have known that the Italians were going to fold so quickly in North Africa.

As covered in other videos, the magazine for the Sten was a copy of the MP28 magazine.

The standard pistol was a revolver with a rimmed cartridge, so they couldn’t use that ammunition. By the time WWII started 9x19mm was one of the most widespread rimless pistol ammunition types available in the world, and it was in commercial production in the UK. They had samples of MP28s to base SMG designs off (the Lanchester SMG itself being simply a close copy of the MP28). It was therefore the most logical choice of calibre for a rimless round.

STEN and Lanchester aside, there existed Biwarip machine-carbine

http://firearms.96.lt/pages/Biwarip.html

It was British design trialed in August 1938 by Small Arms Committee and was chambered for 9×19. It was rejected due to being not accurate enough. We might conclude that 9×19 was deemed as viable sub-machine gun by at least 1 British gun designer and that 9×19 was at least acceptable for said committee.

“(…)What was British 9mm spec?”

https://sites.google.com/site/britmilammo/9mm-parabellum/9mm-parabellum-ball

(…)“Cartridge S.A. Ball 9mm Mark IIz” was approved in September 1943 to design DD/L/14046 and shown in Lists of Changes Paragraph B.9511 dated July 1944.(…)bullet weighed 115 grains(…)propellant charge was 6 grains of Du pont SR.4898, later changed to Nobel’s parabellum Powder(…)Velocity of early production was 1,250 fps at 60 feet but in 1944 this was increased to 1,300 fps at 60 feet(…)

“(…)But that would be feeble Glisenti 9mm(…)”

MAB 38 used another cartridge, namely

M38

9

which was not feeble by 1930s standards.

https://forum.cartridgecollectors.org/t/9x19mm-m38-9/9483

M38 was not feeble by any 9×19mm standard. In modern US terminology it would classify as +P or even +P+. It was developed for and used only in the MAB 38 submachine gun (and subsequent Italian WW2 submachine guns). I have not heard about any accidental use in 9mm Glisenti pistols, but if it did happen, the results were probably quite interesting, to say the least.

RE: British adoption of the 9mm P cartridge… One has to wonder how much effect the idea of being able to use captured German ammunition in case of an invasion of the British Isles had, and if the eventual use of the Inglis Hi-Powers had any influence on it all?

I’d wager that there are probably papers outlining the reasoning. Somewhere. It might simply be that it was easier to reverse-engineer the German magazines and weapons, rather than develop something new. The STEN basically happened because the Lanchester was too expensive to build, and the Lanchester was, if I remember rightly, basically a copy of the MP18/28 family in inch-pattern.

Either way, it was a fortuitous choice.

I find the idea that they’d captured so much Italian ammo so as to make this a no-brainer a bit of a question mark–Very, very few Ordnance types are trusting enough that they’d OK use of such captured stocks without extensive work being done to ensure that the captured ammo wasn’t sabotaged. I seem to recall that there was tank ammo that they re-purposed which was basically remanufactured in-theater, before being issued out to our tankers. I think that was armor-piercing projectiles that they simply put on US or UK casings…

If only people would use rational thinking rather than crony/emotional thinking for arms procurement. Perhaps then they’d actually get better strategies to go with the stuff they bought.

Good question about the potential use of German ammo. In 41′ Britain purchased 30 million rounds of German manufactured 9mm from Bolivia and actually issued it to troops. Desperate times indeed.

If I remember correctly, the speed of sound at sea

level is about 1100fps, and 9mm Luger is about 1125-ish. Even allowing for hotter military loads, would it not have been simpler to load a subsonic 9mm round in a mechanically stock Sten, and then manually (quietly) operate the bolt?

Then you’d have all the usual supply problems of two different items which look remarkably similar.

Yes, if the goal was maximum sound suppression, but I don’t think that was the idea. The British wanted a weapon usable by special forces in combat, not an assassination weapon. The Sten in semi-auto still provided a good deal of firepower for the kind of close quarters combat special forces were likely to engage in.

“RUN AWAY!” “RUN AWAY!” (Monty Python.)

As an MP5 instructor, I had the chance of shooting the SD version. It was like shooting a .22 rifle the recoil was so lite. Quiet also.

Sounds like there’s still a sonic crack there on some of the shots

“…ammunition captured from the Italians in Ethiopia and North Africa. But that would be feeble Glisenti 9mm…”(С)

Maybe enough fantasies?

The British military cartridge 9×19 was developed at the end of 1941 for Lanchester.

And it was developed on the basis of the existing experience in the production of such cartridges for the Dominions in the early 1920s. Which was a copy of the early German ammo.

https://aws1.discourse-cdn.com/business6/uploads/cartridgecollectors/original/3X/2/1/2185bebde7a1240ddb8c0f0cd04bfce2633b6a1c.jpeg

In 1941, the cartridge was modified according to a new model with a round nose.

http://militarycartridges.nl/uk/9mm.htm

https://talesfromthesupplydepot.blog/2019/11/30/wartime-9mm-round/

Pardon.

The rate of fire with a bronze bolt was slightly higher than with a steel one, due to less friction of the bronze-steel pair. Their weight is about the same.

Although, I think, the rate of fire could be different in both directions.

I might add that while there was considerable tactical confusion regarding “machine carbines” in British military circles, as well as the lamentable rejection of “gangster guns” in certain quarters, there were actually several tests done with SMGs in the 1930s by the UK, in a variety of different calibers. The 9x19mm cartridge and the Suomi kp/31 were early identified as superior to the other contenders.

By the time WWII broke out, Britain was purchasing very expensive Thompsons in .45 acp. Then came the Lanchester/ MP28.II and finally the Sten. By that time, it was clear that 9x19mm would be the cartridge for “machine carbines.”