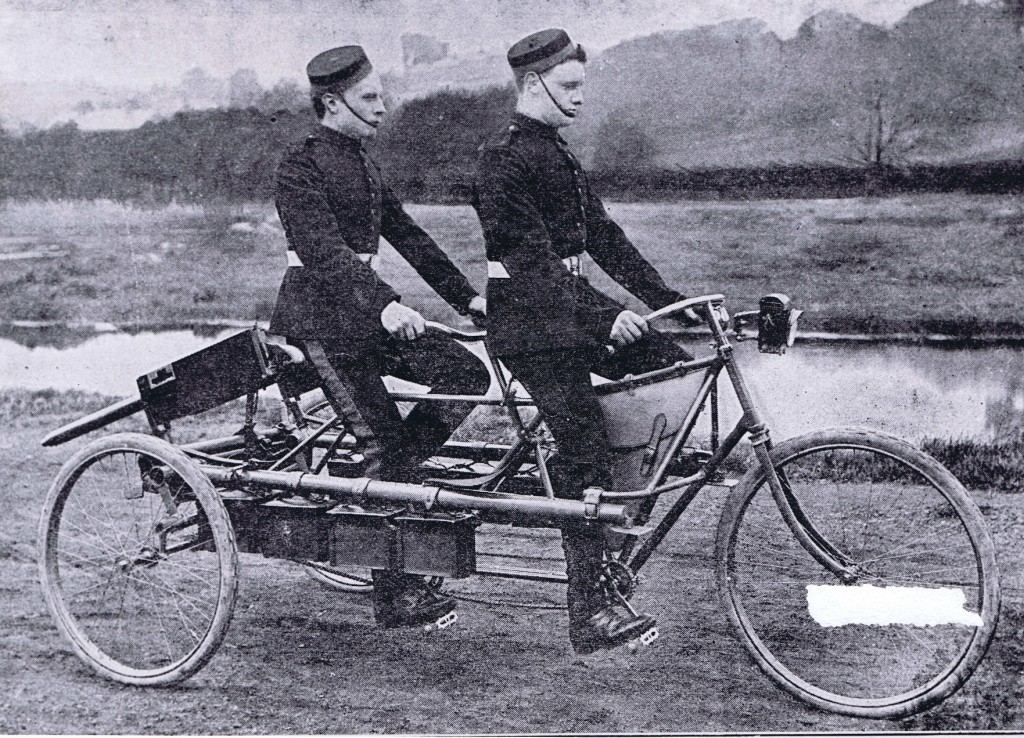

This really has to be the most awesome pedal-powered vehicle ever built:

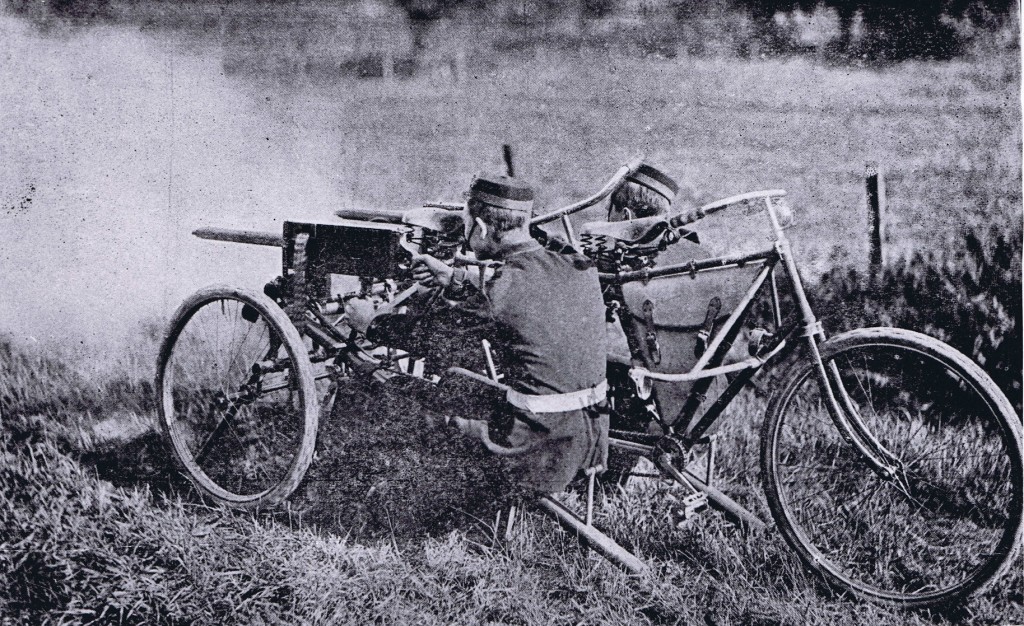

I don’t know the background on the tricycle, but the Maxim guns are very rare air-cooled lightweight models. Like this one:

Ultimately they weren’t light enough to justify the much more limited rate of fire allowed by the non-ventilated shroud and lack of water jacket.

They look like bell boys in the first two photos. Pulling out the Maxim sure changes that opinion in a hurry!!

The fold-up quadrapod legs at the rear of the vehicle with ammunition box stowage are an interesting means of efficient space saving and utilitarian application, as are the lightweight welded steel gunners’ seats that are integral to the rear main legs ( when viewed in the firing position ). Once deployed in the firing position, stability would appear to be quite good.

The tricycle is not as flimsy as first appearances might warrant. The frame is heavily triangulated and braced to withstand anticipated stresses, although whether it was actually enough for the rough-and-tumble of front-line use might be open to question.

The shortened barrels with phosphor-bronze jackets and feed trays on the Maxims are absolutely classic. The pistol grip also appears to be made of phosphor-bronze. Oddly enough, there are no sights on any of the guns in the photographs, so these may have been early demonstrator models.

One wonders if the trike had a freewheel (could coast) or had brakes? Both would make it much more manageable, and usable on a much wider variety of terrain.

Somewhat off point: What is with uniform headgear (in this case the hats) where the strap doesn’t go on or under the solider’s chin, but instead hangs in front of their face in some awkward fashion? How is working or fighting efficiency served by having a strap under your nose or in your lips? I’ve seen this various places – what gives?

The fancy European army uniform died a long, hard death, didn’t it? My first thought is always, “who are those guys, and what did they do to deserve being forced to wear those hats?”

That bicycle would buy a certain amount of respect in the Bronx, I suppose, but I’m guessing it didn’t see much service in WWI.

Ditto, Joel and Steve. My immediate thought was, “Damn. Bellboys are tough in that neighborhood.” Must be NYC.

Royal Horse Artillery…Machine guns were considered as Artillery by the Brits and Americans when first introduced (as a support arm)…only the Germans “got it” and integrated it with the infantry in the attack an defense…

In the last phase of the Second Boer War the British used the bicycle as a means of fast transport.They were considered to be less difficult to maintain than a horse and were a fad in the 1890s. This proved effective and was the backbone of the British “Blockhouse” system along with barbed wire. Also the Royal Irish Constabulary used the bicycle to patrol in the West Counties before the Troubles. They continued to use them long after the establishment of the free State. Belgium and France had bicycle troops to protect borders in 1914. The Italians had a bicycle mount for their twin barrel 9mm machine gun;its use is doubtful.

That would probably be the Villar-Perosa dual machine-gun set-up on the mounting tray and chambered in 9mm Glisenti, correct?

That is it.Thanks

You’re welcome, Andrew. The Villar-Perosa is a fascinating gun with a colorful but largely-forgotten history. Your comments about the history of the bicycle in military applications are so true, and it continues to amaze me that the British General Staff in Malaya consistently underestimated the speed of advance of the opposing Japanese infantry via the extensive use of bicycles, among other significant factors.

The Maxims use a lot of brass, not phosphor bronze. One of the reasons that early British Maxims are so scarce is that they were melted down to recover the brass (more than 20lbs per gun). The Boers had a small number of lightweights, one captured example is now in the New Zealand Army Museum, and others are in Canada and the UK.

Add a little 2-stroke engine to the drive train and you’s have a nice little grid down bug out vehicle. M240 might be a better choice than the old Maxim though.

A MG-3 or PK machine gun would probably be a better choice.

I’d take a Maxim over a 240, but a PK would make for a pretty tough decision…

I don’t see how it would be a better choice. The basic design of the locking system is only a little younger than the Maxim. The M240 is just an upside-down belt-fed BAR. Also, the Maxim is capable of producing equal or greater volumes of fire.

Wasn’t there a bicycle used in the film Blackhawk Down? In the beginning of the movie. A US soldier spying in Mogadishu gets around on a ten speed, then loads it onto a helicopter because its ten miles to the base! He could run to base! So the technology has improved after all, from no brakes to a modern 10 speed.

I have seen a picture in a book somewhere (ofc i can’t find it now), showing two soldiers on a tandem bike in a stationary setup, powering a generator for a radio set.

Also until the start of WW II it was very common to have bikes in service. 15-20 km/h versus 5 walking, and bigger load capacity without having to feed or fuel it makes for a nice mode of transport. (compared to horses).

The Finnish Army’s notion of mobile troops was guys on bicycles until well after WWII. Throughout the war, every infantry division had a bicycle company, and as far as I know the army still has tons of bikes.

Ron Woods brought up a very interesting point about the extensive use of brass in early British Maxims. There seems to be conflicting information on the part of different sources as to whether brass or phosphor-bronze was used in early-model Maxim guns. Could it be possible that both alloys were utilized, depending on the customer, factory of origin and manufacturing timeline?

It is understandable that even historians and other experts can become confused since both alloys are largely copper-based and often appear similar, especially when fully polished.

Pure bronzes typically contain 88% copper and 12% tin. However, there are numerous bronze alloys that have other metals added to tailor their properties to their intended application. Phosphor-bronze, for example, has 3.5%-10% tin and up to 1% phosphorus ( added as an anti-oxidant and fluidity enhancer during the smelting process ). Brass is composed primarily of copper and zinc, and brass alloys can contain iron, tin, aluminum, manganese, lead, nickel and arsenic. Zinc, iron, tin, aluminum and silicone can be added to both phosphor-bronze and non-phosphor bronze to enhance desirable property characteristics.

Herein lies the potential for extreme confusion, because there is a large grey area where the alloy in question can be defined as either a brass or a bronze, or even both. Red brass ( typically 85% copper, 5% tin, 5% lead and 5% zinc, but there are numerous other variations ) is a prominent example of the latter, and there are many other brass / bronze alloys that bridge the traditional definition of what comprises brass or bronze.

This leads us to one of the really intriguing foundation stones of gun manufacture and gunsmithing — metallurgy and metalworking. It might be interesting to get into these topics, especially where “forgotten weapons” are concerned.

Those stupid little infantry “pillbox” hats are still part of the uniform of the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC).