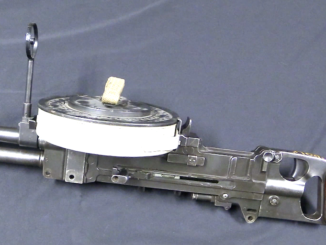

This capping breechloader was patented in the UK by William Terry in 1856, and adopted (in limited numbers) by the British military in 1860. Approved for cavalry use, it was issued to the 18th Hussars, and also bought by a variety of colonial organizations in New Zealand, South Africa, and elsewhere. In addition, it was used to some extent any the Confederacy; both J.E.B Stuart and Jefferson Davis had Terrys in their possession when taken into custody.

Mechanically, the system is a bolt action, with a two-lug, rear-locking rotating bolt. It uses a paper cartridge, the base of which is a thick greased felt pad to provide obturation. Not more than 20,000 were made between 1860 and 1870, when the company shut down. Unlike the Sharps (for example), Terry’s system was not really able to be converted to use metallic cartridges, and so sales dried up as the self-contained metal cartridge became widespread.

Thanks again Ian for another great video. Being a Civil War nut I love getting new information. Please keep up the good work, I enjoy all of the videos.

Very cool! This must be one of the first successful bolt action breechloaders in an era (1850-1880) that was dominated by falling blocks and lever actions… a preview of things to come.

How does the spark from the percussion cap actually ignite the powder charge in the cartridge? Wouldn’t the paper casing inhibit ignition? In other paper cartridge systems that I know of, there was a mechanism to tear the cartridge open to allow the spark from the cap to hit the powder.

The Calisher & Terry used a nitrated paper for the cartridge. Cartridge paper was basically the same as what we consider typing or printer paper today, and it was slightly moistened before rolling it around a wooden dowel mandrel when it was being shaped.

By adding enough potassium nitrate (saltpeter) to the water to impregnate the paper, it ensured that when the flame from the cap hit it, the paper ignited, thus ensuring powder ignition.

It also tended to fully consume the paper, thus avoiding any smouldering bits that might prematurely ignite the next cartridge as it was loaded before the breech could be closed- which could have unpleasant consequences for the shooter.

cheers

eon

Paper cartridge materials are available for black-powder enthusiasts, and will still pack a punch when needed. A large caliber Minie-style bullet shot out of a paper-cartridge-loaded breechloader is more than enough to make any recipient miserable in the immediate aftermath.

Impregnated paper would have saved the old muzzle-loading rifled-musket one step’s worth of loading time, namely that the soldier would not have to bite the cartridge open (and get quite a few grains of bitter powder in his mouth) in order to shove it down the barrel. The potential snag of this idea is having a user stupid enough not to recognize which end of his paper cartridge has the incredibly obvious lead bullet and which end is all powder, unless the percussion cap is stuck on the “tail” end. Did I mess up?

Nope. Of the many (something like 20,000+) disabled rifle-muskets and etc. recovered the day after Gettysburg, the vast majority had an unfired round in the barrel.

About half of the ones that only had one round in had the paper cartridge loaded correctly, but either a plugged percussion nipple or a dud cap. The other half had the cartridge loaded bullet “down”, with the nose of the Minie’ ball firmly up against the breech plug, and neatly blocking the nipple port.

Let’s not even get into the ones with two rounds in the barrel, four or more rounds in, or the one with twenty-three rounds loaded in correct order and a plugged nipple. Not to mention the ones with bent, broken, or missing ramrods.

There is exactly one correct way to load a muzzle-loader, but a great many ways to do it wrong.

cheers

eon

“(…)The potential snag of this idea is having a user stupid enough not to recognize which end of his paper cartridge has the incredibly obvious lead bullet and which end is all powder, unless the percussion cap is stuck on the “tail” end.(…)”

I would say cause of adding percussion caps to cartridge was bit different – percussion caps were relatively small and thus it was easier to fumble than having complete cartridge. Manipulation of percussion cap might be not big deal on shooting range, but imagine doing that under combat stress in frosty air.

Well, if we stick the percussion cap on the tail end of a paper cartridge for “temporary storage” and use the paper cartridge body as a handle to stick the cap on the nipple for the muzzle-loading musket, we’ve eliminated the fumbling problem. And at the same time, the soldier would remember that he would not mash the volatile percussion cap into the end of the paper cartridge that has the bullet on the premise that doing so would blow off his fingers. Anything wrong with this arrangement?

Hate to be historically picky, but here goes: I don’t doubt J.E.B. Stuart possessed a Terry carbine, but as he died of wounds suffered at the Battle of Yellow Tavern there is some question of just who took him into custody when he owned it. Incidentally, Stuart’s wish to try out his new LeMat revolver contributed to his death — he had dismounted at a rail fence to plink at passing Union cavalrymen, when he was potted by Pvt. John Huff of Custer’s unit, a former Berdan’s sharpshooter, and as it turns out, no mean pistol shot.

The colonies of Queensland and NSW in Australia also bought some of these.

The Kelly gang ended up with a couple captured from police at Jerilderie.

No nitrate is needed to punch through the wall of the cartridge. Ordinary writing paper in two layers pierced by a force capsule.

Impregnation with nitrate began to be used later, yes, for the complete combustion of the remaining shells.

In the place where the paper lay in three layers, a strip could be drawn so that this place was not opposite the ignition hole. And they could not draw.

https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/britishmilitariaforums/making-monkey-tail-cartridges-that-work-t23349.html

https://going-postal.com/2019/02/milestones-in-nineteenth-century-firearms-development-part-six/