Designed in 1939 by S&W engineer Edward Pomeroy, the S&W Light Rifle is an extremely well manufactured but rather poorly thought out carbine. It is a 9mm Parabellum open-bolt, semiautomatic, blowback carbine feeding from 20-round magazines. It was tested by the US military at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, and rejected for a number of reasons, including not being in the US standard .45 ACP cartridge and not being full automatic. However, the British were in dire need of small arms, and S&W decided to pursue sales to the UK rather than redesign the gun to US taste.

The UK ordered a large number, but upon putting the first guns through trials found them to be unsatisfactory. The 9x19mm loading used by the British was substantially hotter than what S&W had used in designing the weapon, and receiver endocarps were shearing off in as few as 1000 rounds under British testing. The British cancelled the order, and took delivery of S&W revolvers in lieu of a refund on their (sizable) down payment. At the end of the war, all but 5 of the 1,010 guns delivered were destroyed.

In 1974, crates of leftover Light Rifles were discovered in the basement of S&W – 137 MkI types and 80 MkII types. These were sold as a batch to Bill Orr of GT Distributors, who then sold them on the commercial market. Orr also petitioned ATF to exempt the guns from NFA short-barreled rifle classification (the guns have 9.75” barrels), and was successful – so these transfer as ordinary rifles despite their short barrels.

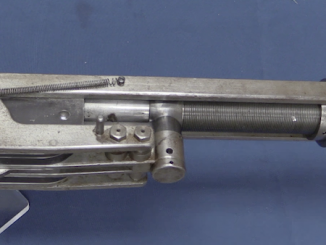

The difference between the MkI and MkII is the safety and the firing pin. The MkI has a lever safety which locks the bolt in the rearward position, and a floating firing pin with a lever actuator like a Beretta M38. The MkII has a rotary sleeve safety which locks the bolt either forward or rearward (a better system), and a fixed firing pin milled into the bolt face. Note that contrary to most literature, the MkII receiver was not strengthened to alleviate the durability problems found by British testing.

What we have here is a failure to communicate! I wonder if anyone mentioned powder loads in the original design specifications, which would have helped everyone in the development process. Perhaps the best option for the situation is to radically change the receiver design in materials and dimensions to accommodate overcharged ammunition while maintaining some form of ergonomic comfort! I could be wrong.

Its not loads!!,

its the unbelievable engeneering stupidity that designed this, with bolt nearly bottoming out to sear position, coupled with shallow threads, without even any kind of rubber or leather buffer (not to start on ejection port magwell combo idea…)

I wonder how come british before buying had not one sane and mechanically intelligent person examine it field stripped and to conclude it is a total failure, you dont need to fire 1 round to see it.

Beauty of the manufacture, flutes, slick looks just augments how wasted opportunity this is – but apparently we can connect it to our human relations also, and how something pleasant looking outside is often not the same on the inside.

“unbelievable engeneering stupidity that designed this”

Wait, do you want to stay it would not work reliably even if using cartridge which are in originally specified range of parameters? If yes, I presume S&W must detect such serious flaw, question is when and more importantly what actions were undertaken as response?

“wonder how come british (…) not (…) to conclude it is a total failure”

Well, I see it is example that they need such type of weapon (substitute for sub-machine) very badly, so enthusiastically made deal. Possibly without actions from British, these weapons would be mothballed and left in storage, then forgotten, then after tens of years sold as curiosities.

“how wasted opportunity this is”

This lead to question what (or who) sparked development of S&W Light Rifle, when and what were requirements? S&W earlier produced Model 1913 automatic pistol based on European (Clément) design, why they did not were looking in that direction?

It might be argued that they wanted Light Rifle, not sub-machine gun, which designs were widely available in Europe, unlike Light Rifles, but I presume they would be able to redesign selective-fire mechanism into self-loading only. Mass of S&W Light Rifle was not much less than then available European sub-machine guns. For comparison MP.28,II weighted 4 kg against 3,9 kg of S&W Light Rifle (both empty) and also, they could during conversion from selective-fire to self-loading drop barrel shroud, as there would be less heat.

“Wait, do you want to stay it would not work reliably even if using cartridge which are in originally specified range of parameters?”

Absolutely yes, designing a gun that cocks the bolt only by smacking the endcap (every time you fire it!) and that has shallow threads is a disaster waiting to happen, but they will break sooner or later – and if you choose to use too light loads, then it may not even be pulled back far enough, so you would get FA mag dump!

For example, where it works – Marlin Camp Carbine (9mm, which is extremely comparable in its role to S&W, but it is closed bolt)

has very light bolt, with short travel, but at the end of the travel it bumps against plastic buffer and big chunk of steel behind it (part of the upper receiver) – check it out here:

http://www.yankeegunnuts.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/MarlinCampCarbine_06.jpg

Thats not ideal system, imho, but for example, if you would remove that system and put some kind of shallow threaded affair, like in S&W, I suspect after few hundred rounds threads would break and bolt would come out at the back flying like a bird !

Since the stock is right behind, unfortunate shooter would get a temporary, 1 second experience of a heavyweight boxing match, LOL.

Why did they make it so ?

Hard to answer, but it falls in the same category as why did they make Blish lock in Thompson that actually don’t work at all in practice.

It is possible there were similar misconceptions, for example, I’m guessing here, but maybe there were some false assumptions taken from the (apparently wrong) science books at the time, about the strength of treads or steel, that “guaranteed” they will hold (or it was measurement of constant force, not taking in mind short sharp blows), so maybe the designer held to that parameter.

And to remedy it, you would need to redesign almost whole gun, so it’s cheaper to scrap it.

Also, for the barrel, maybe there were some myths at the time that fluting it will actually improve accuracy (also an example guess here), of course all such myths were by the time as arms development progressed, busted and deemed unnecessary (“blish lock ? movable firing pin in open bolt gun? etc. discard it all ASAP and stick with simple fixed FP”)

We would need to travel back in time to put ourselves in 1930s mindset and knowledge, to understand it.

But as Ian once said it perfectly, this channel/blog is about looking at the designs that ended up “forgotten” primarily by their own peculiar features that lead to a dead end in gun science and development,

and so we examine them and conclude from today perspective what worked and what not, and why not.

In my experience, British army issue 9mm ammo has always been loaded on the hot side of hot. I don’t suppose S&W could have foreseen that, if their design was intended for commercial Luger rounds.

But also, from what I’ve experienced in the way of British WW2 sidearms, the M&P’s supplied by S&W were the best revolvers.

I think that at that time, the 9mm Parabellum ammunition used by Britain was hot loaded stuff captured from the Italians in North Africa. It was meant to be used in submachine guns only, as the Italians did not use 9mm Para as a pistol round then.

Correct. The Sten and Lanchester SMGs, or “machine carbines”, were designed to use 9 x 19mm precisely because of the captured Italian 9mm, intended for the Beretta Model 1938 SMG.

The only self-loading pistol cartridges manufactured in Britain at the time were .38 Colt Automatic (not Super), .455 Webley SL, .32 ACP, and .380 ACP. None of them were considered suitable for a military weapon; the .32 and .380 were not powerful enough, the .38 Automatic’s accuracy was indifferent, and weapons for the .455in WSL hadn’t been made since the end of WW1.

Early on, somebody at the Ministry of Supply demanded that any new “self-loading” weapon be chambered for 0.380in revolver, aka .38 S&W, that being the cartridge used in the Enfield and Webley MK IV service revolvers. As much as anything else, I suspect that was an attempt to kill any and all such projects, by senior officers who still viewed any self-loading weapon smaller than a Bren as a “gangster gun” due to American movies.

When Garibaldi’s forces surrendered, the British found themselves with over 100 million rounds of 9 x 19mm ammunition for the M38s. They were 124 gr. FMJ at over 1,500 f/s from the SMG barrel, making them “+P” loads by modern SAAMI standards. The Sten, Lanchester, and P-35 pistols (originally intended for China) ended up as the standard weapons in 9 x 19mm simply because they could stand up to the pressures and etc. of this hot-loaded round, which is definitely in .357 Magnum territory in terms of energy delivery.

The S&W Light Rifle, by comparison, was designed around U.S. commercial 9mm Luger (its official U.S. designation), which at the time was usually a 124 gr. bullet, either FMJ or JSP, at 1,050 F/S from a 4-inch pistol barrel. This puts it in the same energy and pressure range as the .38 Special High Speed aka .38/44 revolver round, the forerunner of the .357 Magnum. While certainly fairly powerful, it didn’t generate the breech pressures of the Italian/British standard 9mm.

No wonder the S&W didn’t last long in British service.

cheers

eon

Eon:

The official idea to use the .38 revolver round wasn’t entirely daft. Its dimensions are almost the same as 9mm Para, the rim is not huge, so the magazine would only have to have been slightly curved, and, most importantly, it was in production. However, it only had the sort of energy of a .380 auto, so the capture of all that Italian ammunition turned out very lucky for Britain.

Well, it may not have been entirely daft, but nevertheless it was pretty stupid, especially if one understands how SMGs are supposed to and were in fact used. The .38/200 was a very low velocity cartridge, even more so than than the original .38 S&W with a 145 grain bullet, which would have severely limited the practical effective range of an SMG. Basically hitting small (e.g. upper torso) or moving targets beyond about 50 yards would have been quite difficult with such as slow moving bullet.

That’s not true – the Lanchester was practically designed to use every type of 9x19mm ammo except 9mm Beretta. The Italian cartridge disagreed with the Lanchester and its use was advised against.

Aug:

An interesting point. The Lanchester was a panic design from 1940, and was pretty much a straight copy of the MP18, and so was naturally 9mm Para. I assume that the British government must have had some sort of plan to produce 9mm as well, as they could hardly have foreseen that we would capture 100 million rounds from the Italians.

I have never heard that the Lanchester did not like this hot Italian ammunition. I find that odd. The Lanchester was built out of solid steel, and could not be less like a Sten gun, yet the Stens seem to have coped. That’s a bit of a head scratcher.

“…receiver endocarps were shearing off in as few as 1000 rounds under British testing.”

The receiver is a peach pit?

I think he meant to say “end caps.”

And here I thought “endocarp” was a new species of fish! 🙂

I’m sure he did. It’s probably an instance of “Damn You, Auto-Correct!”.

Odd that an old and experienced firm like S&W got so many things wrong besides the ammo compatibility problem.

Well, first of all, S&W’s only previous venture into self-loading design was the S&W .35 automatic (1913-22), and its successor the Model 32 (1923-37), both blowbacks based on the Clement patents. They had never designed a weapon for even a round as powerful as U.S. “domestic” 9mm before.

Second, the light rifle was originally intended for police, bank guard, and prison guard use here in the U.S., not for military use. This was why it was semi-automatic only instead of selective fire, to avoid special licensing provisions after the NFA 1934. Its natural competitors were the Reising Model 50 semi-auto carbine in .45 ACP, and the Winchester Model 10 semi-auto carbine in .351 WSL. Both of which also tended to fail badly in military use.

Third, when the British Purchasing Commission contracted for the S&W light rifles in 9 x 19mm, the specification called for them to be able to handle “standard 9mm ammunition”. The BPC neglected to mention, or possibly just wasn’t aware, that the 9 x 19mm ammunition the British forces would be using was substantially more powerful and higher-pressured than the U.S. standard.

I don’t think you can rally blame Smith & Wesson for the results. it’s more or less a lesson in the old engineer’s axiom, “make sure the customer tells you what specifications they really need, as opposed to them just telling you ‘that’s good enough'”.

cheers

eon

You’re thinking of the Winchester 07. The model 10 is nearly identical but in .401 calibre and was already out of production. The 07 remained in production until 1958 and was in .351 wsl. Source: I own and shoot a Winchester model 10.

“I don’t think you can rally blame Smith & Wesson for the results. it’s more or less a lesson in the old engineer’s axiom, “make sure the customer tells you what specifications they really need, as opposed to them just telling you ‘that’s good enough’”.”

I would say, it is reminder that weapon (gun) and ammunition (cartridge) are tightly joined duet, so when wanting to modify one of them, question how it would affect that second must be answered. In case of ammunition this should be done for all weapons, which are supposed to work with it.

“light rifle was originally intended for police, bank guard, and prison guard use here in the U.S., not for military use. This was why it was semi-automatic only instead of selective fire, to avoid special licensing provisions after the NFA 1934. Its natural competitors were the Reising Model 50 semi-auto carbine in .45 ACP, and the Winchester Model 10 semi-auto carbine in .351 WSL.”

So there seems to be decision made, which later proved to be unfortunate, but it is hard to blame S&W for that, taking in account that they could not see future.

Who could say in 1938 or 1939 that sub-machine guns would be used in such numbers in world war, Great Britain would want to purchase big number of such weapons, despite showing reluctance toward them in 1920s and 1930s and finally will capture big number of 9×19 cartridges from Italians?

Ian,

At the beginning of this year you promised to offer all sorts of exciting new content. It was as though you were casting your vision for the future of Forgotten Weapons, hoping to realize a more robust, diverse, and “edutaining” website.

Well, it seems like you have not only met those goals, but you have far exceeded the mark. Outstanding. (On on the internet these days, that’s actually quite a feat.)

For the rest of you mostly expert level regular commentators, watch this video a second time through, only this time, forget about the technical aspects of the rifle, and just listen to Ian’s delivery. It’s not just years of experience showing their worth here. There’s a fluidity to the breakdown of elements, seamlessly interchanging between the pieces parts of the rifle, and the story behind the rifle.

All I’m saying is that after years of running this site, shooting countless hours of video, all the travel, all the editing, all the unseen efforts that sometimes make what seems like a dream job actually just plain hard work… This simple video is an example of the culmination of all of the above. What you are seeing is a master at work, in his element, almost effortlessly going about the business of dissecting yet another gun, while at the same time, clearly enjoying the process. It’s like witnessing the intersection of talent, persistence, and passion, all embodied in a guy who looks like Wild Bill Hickok, lol.

Point being, FW is an oddly potent force on the internet, quietly advocating the benefits of firearms, as opposed to the general aversion (or downright hatred) much of society at large has towards guns. What a genius way to approach the topic, by showing the engineering aspects, intricacies from one type or another, what works, and mostly, what did not. For those with a mechanical mindset, and even a passing interest in firearms, this site is like a post-graduate level college course in innovation and manufacture. And also abject failures.

We are all better served because of Ian’s work.

And let’s not forget how much grace and leeway is given to be able to have the discussions we do, down here in the comments section. It’s the second best thing about this website. A true freedom for people from all over the world to add their knowledge and input. Keep up the civil discourse, guys. It’s one of the things that sets Forgotten Weapons above the fray.

As far as the “light rifle” is concerned, man that thing looked like a sleek little .308 at first blush. I wonder if someone could take just the exterior profile, more or less, and create something along those lines, that would, umm, you know… not blow up in your hands. Love the shape, but S&W gets an award here for worst execution ever.

Just my two cents…

Ian and neighbor -J-,

This video is a good example of why I LOVE Forgotten Weapons. The detail in the photography is so good, you almost think you are holding the weapon and “discovering” its intricacies yourself (with an armorer’s dialog instructing you). Amazing!

Here’s the part about the S&W from my ongoing manuscript about SMGs in WWII:

“Since the UK purchased U.S.-made Smith and Wesson revolvers chambered for the .38 S&W revolver cartridge, it appears that in the spring of 1939, one or another British purchaser got wind of a prototype “light rifle” developed by the firm under the research and development engineer team headed by Joseph Norman and Edward Pomeroy at Springfield, Massachusetts. Details about this acquisition, which ultimately proved to be a boondoggle, remain sketchy. Nonetheless, it appears that prototypes of the subcarbine—it fired 9mm pistol cartridges, but only one at a time even though it was an open bolt, blow-back operated weapon—along with drawings, arrived in Britain by June 1939, at the time the Suomi SMG in 9mm was still undergoing trials. Speculatively, this might have been the rationale for having the Smith & Wesson light rifle evaluated. It seems that either once World War II broke out, or during the post-Dunkirk scramble, His Majesty’s government transferred a million USD to the renowned U.S. gun company.

Thus it came to pass that approximately 1,010 of a scheduled 2,000 plus S&W semi-auto-only 9x19mm “machine carbines” became substitute standard arms, mostly in the hands of the Admiralty. An unusual retro-futuristic weapon, the S&W carbine had the drawbacks of being simultaneously too expensive to manufacture and possessed of too many bugs to work out of the design. S&W took tremendous pride and care in protecting their brand, and so only the best materials and craftsmanship would do. On paper, it had 46 main component parts, but this totaled out to about 90 parts. Realistically, this proved far too many. The majority of parts required extensive milling and machining by skilled craftsmen. The barrel, for example, was 9-3/4-in. long, made from chrome nickel steel, included 12 longitudinal flutes, each produced by a separate milling operation. It screwed into a drop-forged, manganese steel receiver tube, that itself fitted into a separate ejector tube and magazine housing assembly at the front, and a “frame” that included the butt-stock fittings and trigger housing in the rear. Thus, the receiver was three parts made from the most lavishly expensive steels, where just one part would do. The need to make the rear of the actual receiver thin enough to fit into the rear frame, and keep the weight of the piece down, entailed a so-called “butt nut” incorporating the “eye” for the pin to lock the frame/stock and receiver together, and within the frame, closing the receiver tube and supporting the return spring assembly. The threads proved too thin for the powerful 9mm cartridges adopted, and so it would break after a few thousand rounds had been fired—battered by the reciprocating bolt to the point of failure.

A large rectangular, brick-shaped metal tube open along the front and a portion of the bottom formed a combined magazine housing and a chute down which empty cartridge cases would by shunted upon ejection. A 20-rd. magazine—one of two shipped with the gun—was inserted through the front of the chute, and snapped into place via a spring-loaded magazine latch at the bottom of the rectilinear tube. While it must be owned that the interior mechanisms were well sealed against the ingress of dirt, with only a reciprocating cocking lever and its slot, the Achilles’ heel of the system was the utter inability to access the actual ejection port, feed-way and chamber, hidden by the combined ejector tube/magazine housing. If an “immediate action drill” failed to clear the weapon, some disassembly would be required. Smith and Wesson readied a Mk.II version. This included a rotating, twistable sleeve over the receiver, which would close off the slot for the cocking handle, and lock the bolt in place so it would not travel back if the carbine fell, such that the blow drew the heavy bolt back against the main spring’s tension enough to pick up and fire a cartridge on the return.

Lastly, the rear sights of a firearm that might be reasonably expected to reach out to 200, or at the extreme 300-yards, had a micrometer-adjusted rear sight. The user firing it would turn an adjustment wheel a single click for 100-yards, 6 clicks for 200yds. Should it prove necessary to attempt longer shots, 15 clicks brought the sight to 300yds., and 22 to 400yds. A 115gr. 9mm bullet might be expected to drop something like 26 feet at that extreme-for-a-pistol-cartridge range. For all that, windage adjustment—to the left or right, not just up and down—was fixed at the factory. It would seem that production began in February 1941, and ran through mid-April before it was halted.

Ultimately, the contract cancelled, demands for a refund led to legal wrangles. The firm in Springfield, Massachusetts had apparently spent $870,000 dollars on the project and could not remit the full sum. Instead, again speculatively given the dearth of information, it would appear that S&W delivered almost all completed Model 1940s in inventory, the tools, gauges, and any remaining parts, and renegotiated the return via supply of M&P revolvers in the British .380-in. chambering at lower cost. Fortunately for the UK, the month previous to the American import’s cessation, 7 March 1941 to be exact, the Sten Mk.I was formally adopted. As will be seen, the Sten was by no means the only “machine carbine” acquired and used. After this obscure digression, we must return to the context, character, and times of the weapon’s development, design, and its makers.”

“unusual retro-futuristic weapon, the S&W carbine”

I have feeling that I saw very similar weapon earlier, after some thinking I concluded that it is generally similar to so-called OVP 1918, c.f. 5th image from top:

http://modernfirearms.net/en/submachine-guns/italy-submachine-guns/villar-perosa-eng/

with the main visual difference being magazine sticking and also appearing less massive, as there is not chute for ejected cases.

It indeed would be fit for so-called raygun gothic setting.

is: “(…)sticking(…)”

should be: “(…)sticking upwards(…)”

By Jove! Daweo, you are correct, I think. The rotating sleeve on the Revelli, aka. OVP-misnomer has a fluted sleeve over the receiver tube as the charging handle. The S&W light rifle 9mm Mk.II has the fluted sleeve to serve as a rotating safety collar to keep the blowback bolt either all the way forward and immovable, or all the way back and immovable to prevent a jarring/ inertia discharge.

Oddly, Ian’s review of the Revelli revealed that while it was ostensibly set up for the 9mm Glisenti, that the actual cartridges for it were quite hot, and seemingly didn’t pose too many problems. On the other hand, the S&W light rifle was a 9mm, but too delicate for the +P British 9mm “machine carbine” cartridge. Of course, had the S&W been made with a single-piece receiver instead of the three that it had, and concomitantly the receiver cap didn’t have to be undersized to fit into the butt-stock element, it might have been made strong enough?

Is it possible we have a challenger to the Cobray Terminator?

“challenger to the Cobray Terminator”

For title of…?

I see crucial difference here: S&W Light Rifle was overtaken by turmoil of events and, assuming that it would work properly with intended variant of 9×19 cartridge, it might get some success in police or similar application, c.f. Reising sub-machine gun which proved to be unfit for military application, but quite good for police.