Before Samuel Colt popularized the mechanical connection between the revolver hammer and cylinder, the revolvers being made were manually operated. This example is a copy of a third type Collier (that is to say, a gun made originally for percussion caps). After firing, one pulls the cylinder back against a spring and rotates to the next chamber. A shield at the front of the cylinder protects the chambers, and the cylinder mouth is chamfered to seal into the barrel, preventing most of the gas leakage at the cylinder gap. This beautiful ornate example was made by Salvatore Mazza of Naples (the official armorer of the Prince of Sicily, he would like you to know!), most likely in the 1820s.

Related Articles

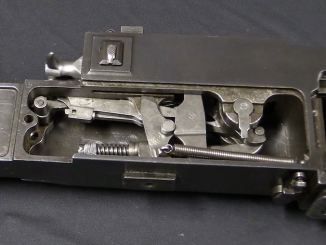

Heavy MGs

Italy’s WW1 Heavy Machine Gun: FIAT-Revelli Modello 1914

Italy was the first major adopter of the Maxim heavy machine gun and had several hundred by 1914 – but wanted to have a domestic design in production as well. The Italian government and military […]

Semiauto pistol

RIA: Beretta Model 1931 (Video)

With the development of the Model 1931, Beretta had nearly arrived at the first really popular pistol (the 1934/5). The 1931 was the result of taking the exposed-hammer 1923 design, shrinking the frame down to […]

Submachine Guns

The Beretta PM-12S Submachine Gun

For several decades, the Beretta company’s handguns and submachine guns were nearly all designed by the very talented Tulio Marengoni…but nothing can last forever. After World War 2, Beretta engineer Domenico Salza began working on […]

The ramrod seems just a little shorter than I would expect for seating the bullet within the chamber.

I thought the same thing. It appears the rod would only get the ball down to the end of the barrel. That would be a good reason for the enhanced chamber seal if the cylinders only hold the powder charge.

Ironically, this allows a higher hold relative to the bore axis than the “advanced” MTR-8.

Ian said in his earlier Collier video, “The hammer is cocked which means I can pull the cylinder back and rotate it.”

Strongarm added, “Falling hammer should activate a block for the cylinder not to move backward during firing.”

“Certainly he [Collier] was aware of the problem with the barrel-to-cylinder gap, because he engineered a system that reminds us of the later Nagant revolver. He managed to seal off the rear end of the barrel where it joined the cylinder and therefore didn’t have that ring of fire when he capped one off.” Collier & Colt: The Origins of the Revolver, by Wiley Clapp, 9/26/20 American Rifleman.

Maybe the stiff cocking force is because there is a cylinder locking mechanism that engages as the hammer drops.

Korean subtitles???

That plate in front of the cylinder is likely to keep the firing cylinder from flashing over to the others.