I had a reader send me a link to this article, which was written in 1981 by Lt. Cdr. W.M. Bisset and published in Scientia Militaria – the South African Journal of Military Studies (vol 11, nr 3). It is available in its original PDF form for download, but I have transcribed it into HTML here for easier access.

The Reider is one of the handful of semiauto conversions of the Lee Enfield rifle that were developed in WWI and WWII – the others being the Charlton, Electrolux Charlton, Howell, and Howard Francis. Very little information is out there about these guns, and it was exciting to find this article!

The Rieder Automatic Rifle Attachment

by Lt Cdr W. M. Bisset*

In March 1981, Mrs H. J. R. Rieder donated her husband’s presentation British .303 SMLE Rifle No 1 Mark III (number M-45374) with the Rieder Automatic Rifle Attachment to the Military Museum at the Castle in Cape Town. With it were a number of photographs, letters, documents and plans concerning this once secret invention which was tested outside the Castle during the Second World War. Fortunately, the documents donated by Mrs Rieder include a list of the numbers of the 18 rifles to which Mr Rieder’s automatic attachment was fitted and it is hoped that the publication of this information will lead to the discovery of some of them and be of considerable interest to their present owners.

France surrendered on 17 June 1940 and to many a swift German victory seemed inevitable. In July 1940, Mr H. J. R. Rieder discussed the simple conversion of a standard .303 rifle to a full automatic rifle with Lt Col M. E. Ross, the Staff Officer A11 at Cape Command Headquarters in the Castle.(1) Mr Rieder, a radio and television experimenter and inventor, was employed in the Mechanician Department of the General Post Office in Cape Town. Although of German ancestry he had served in the Royal Corps of Signals during the First World War.(2)

On 22 July 1940 Mr Rieder wrote to the Officer Commanding Cape Command requesting the loan of ‘one standard service rifle for minor alterations and fitting of conversion unit for demonstration purposes only’. Mr Rieder added that the normal operation of the rifle would not be impaired and that an old used rifle would be quite adequate.

In a reply dated 3 August 1940 a Lieutenant-Colonel wrote on behalf of the Director-General of Technical Services that Mr Rieder should be asked ‘to explain the principle which he proposed to adopt and submit drawings or sketches of his design’. The writer doubted whether an automatic rifle was of much value, since none had been adopted to any great extent by any of the powers. He added that the ammunition supply was one difficulty.

On 23 September 1940 the Deputy Director of Coast Artillery, Lt Col H. E. Cilliers, authorised Mr Rieder to ‘hold in his possession one rifle Mk 111 No 45374’ for experimental purposes, but on 18 November 1940 he wrote that the Senior Stores Officer was ‘pressing for its return’ and requested a progress report.

Mr Rieder manufactured his automatic rifle attachment in his home, Windyways, 37, Upper Glengariff Road, Three Anchor Bay and was supplied with blanks with which to test it. A kingsize silencer deadened the noise which would otherwise have aroused the suspicions of the neighbours.(3) Mr P. D. Rieder, the youngest son of the inventor, recalls that his father was later granted a temporary transfer to the UDF and wore army uniform. All subsequent work on the invention took place in an upstairs workshop in the Castle and a sergeant was assigned the task of assisting Mr Rieder.(4) A detailed description of the Rieder Automatic Rifle Attachment and photographs of the invention were forwarded to the Senior Naval Officer, Simonstown on 2 January 1941 and to the Director-General of War Supplies, Dr H. J. van der Bijl, the following day.

A letter from the only cameraman permitted to be present, mentions that separate demonstrations for the Admiralty and Director-General of War Supplies were arranged. Fortunately, the African Film Productions cameraman, whose name is not recorded, has included the familiar stone walls of the Castle in some of the photographs of the demonstrations. The cameraman advised his General Manager on 14 January 1941 that permission for him to photograph the rifle had only been granted on condition that the company work through a Mr Wilson who was responsible for the arrangements concerning the release of the story. However, a telegram from DEOPS Pretoria to DECHIEF Cape Town dated 22 January 1941 stated that the negatives of films of the invention were being returned at once, care of Capt Stodel and that neither copies nor negatives had been made.

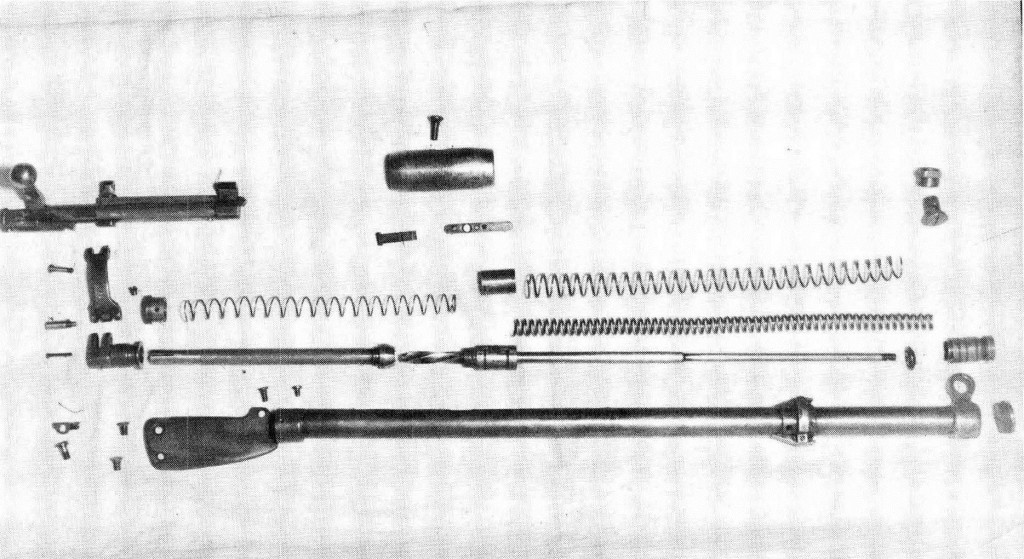

Attachment, extra handles and a larger magazine

Mr Rieder’s automatic rifle attachment made it possible for the ordinary service .303 rifle to operate as an automatic weapon by using the gas or pressure generated by the fired cartridge. Mr Rieder considered that the merits of the rifle attachment were its lightness (approximately 2.5 lbs [ed: 1.1kg]), simple construction and fitting, relative freedom from stoppages, low production costs and ease of loading. The attachment did not prevent the rifle from being used as an ordinary rifle and ‘single shots could be fired with automatic loading’.

The only disadvantage listed by Mr Rieder was overheating after about 100 rounds had been fired but this he expected to overcome. In a letter to the Director-General of War Supplies, Director-General of Technical Services and Mr Rieder dated 31 January 1941, the Officer Commanding the Technical Services Workshops at the New Drill Hall, Maj E. P. Edwards, wrote that during demonstrations the extractor and loading springs had caused problems because they were made from piano wire which did not retain the correct length and weight. ‘This problem and an incorrectly designed check spring were overcome in a new model of the attachment. Maj Edwards considered that this invention might be as free from defects as the ordinary machine gun’. Another advantage was that scarcely any oil was required and although it had a dust cover it stood up well to field conditions.

Under the heading ‘remarks’ Maj Edwards suggested that the eye-guard could be used for fitting an adjustable aperture sight to offset the possible difficulty of aligning the service sight caused by the rapid vibration of the rifle. Single shots could be fired by releasing the trigger quickly or alternatively the rifle could be brought to service conditions by closing the gas vent.

Although Maj Edwards wrote that it was essential that a type of elongated ring foresight be fitted, he pointed out that the introduction of tracer bullets (1 in 3) and using the hose pipe method would be useless because of the speed of modern enemy aircraft upon which the .303 bullet had ‘very little effect other than the moral aspect’.(5)

In a letter to OC Technical Services dated 16 June 1941 Mr Rieder requested a further extension of his temporary transfer to the Defence Department because it had proved impossible to obtain a suitable type of steel spring in the Union and this and other small improvements had impeded progress. Nonetheless, he hoped that ‘perfection would be accomplished in the near future’.

On 18 June 1941 Mr Rieder advised the Officer Commanding Technical Services Workshops in writing that his experiments had reached finality and that it would now be possible to complete the remaining sixteen rifles for demonstration purposes. He requested a further period of about six weeks to complete the task.

On 10 October 1944 Cdr H. S. Gracie, RN presented Mr Rieder with the first .303 rifle (Number M-45374) to be fitted with the Rieder Automatic Rifle Attachment on behalf of the Admiralty.(6)

an army officer and a civilian after a demonstration

outside the Castle in Cape Town

Although three rifles fitted with Mr Rieder’s invention were sent overseas, it was never adopted.(7) Nonetheless, Mr Rieder’s ingenuity and industry in one of the darkest hours of the Second World War, deserve the highest praise. Mrs Rieder’s gift, now displayed near the scene of the two demonstrations outside the Castle and the documents and photographs relating to it, have also helped fill another gap in the history of our most important national monument.

.303 Rifles fitted with the Rieder Automatic Rifle Attachment

M-45374 – Obtained by Mr Rieder. Presented to Mr Rieder by the Admiralty on 10 October 1944. Now in the Military Museum The Castle.

Eighteen rifles received from SSOT

Listed as being ‘partly converted to original plan and now at Cape Town’ on 20 September 1941:

892462

239133

F59817

G47054

892868

N8109

236139

S48250

Rifles completed and converted to new plan now at Cape Town ‘Susie’. (Taken to Pretoria by McClelland). Sent to Pretoria:

F53065

F68561

H43785

F45222

H86891

250675

Rifles Sent Overseas

Converted to original plan Converted to new plan 25.8.41 ‘Bertha’. (Taken to Pretoria by McClelland on date not recorded):

8134

F26776

F59724

* Lt Cdr W. M. Bisset is SO Military Musea, WP Command

Endnotes

(1) Letter from Mr Rieder to OC Cape Command dated 22 July 1940.

(2) Information provided by Mr P. D. Rieder and obituary in The Cape Times 23 November 1954.

(3) Information provided by Mr P. D. Rieder.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Letter TSW 840/1 dated 31 January 1941.

(6) Letter from Cdr H. S. Gracie (Office of Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic) dated 10 October 1944.

(7) Letter TSW 840/1 dated 20 September 1941.

Shooting an Enfield where the bolt jumps into your face on every round must take some getting used to. It also looks like a pretty machining intensive conversion, including manufacture of a new bolt. Even if it worked well I can’t see it being very cost efficient to make a poor man’s Bren.

Another weird SMLE conversion – in the early 70s I remember seeing (almost certainly in American Rifleman) an article about a WW1 era bullpup conversion of a Lee-Enfield. It had two ten-round magazines in a W-formation, think there was a lever to switch from front to back mags, and the trigger group was in front of the mags. Very short and compact; I seem to recall the article mentioning that having a .303 chamber alongside of the user’s head instead of several inches in front of it was a unique recoil experience, and was probably why the design never got very far past the prototype/ test-firing stage.

Jim,

The rifle you’re thinking of was the Thorneycroft Rifle. It was allegedly the world’s first bullpub rifle. It was considered too unorthodox for consideration at that time.

The Thorneycroft was not a Lee-Enfield conversion, but in fact a totally new design. It was a joint collaboration between James Baird Thorneycroft and Moubray Gore Farquhar (the latter went on to design machine guns). About 3 different versions were made. I think the main reason that nothing ever became of it was not because it was unorthodox (although it was), but because the British Army had just adopted the SMLE and didn’t particularly want to consider another design.

Most of these oddball conversions seem to require almost as much machine work and manufacturing capacity to build the conversion parts as it would take to build an entirely new weapon, particularly a tube-bodied submachinegun, a-la the STEN. Interesting from a collector’s or inventor’s standpoint, but useless as a practical combat weapon, and overall a waste of time and scarce resources, including 18 perfectly good Enfield rifles.

Not really. The barrel and receiver were the time-intensive parts, judging from Colvin’s “US Rifles and Machine Guns.” Just those two parts are probably 35-40% of production time.

Plus, other than the conversion bits, it’s a standard Enfield, and troops were already trained to use that and REME armorers had the parts and knew how to fix them. But in 1940 most militaries weren’t persuaded of the advantages of an autoloading rifle, and America was ramping production of the P-14 back up, and there was the promise of Lend-Lease Garands and ’06 ammunition to feed them; someone felt the optimal path was for Britain to stay with what they had and run 24/7 making them. In retrospect, I think they made the correct decision.

Regardless of how much machining these would require, the real benefit to converting a rifle to a mock LMG was the material savings. In wartime, labor can be very, very cheap between either patriotic zeal or slave labor, but the real cost is in materials. LMGs require a lot of steel to be milled out of a block, whereas this conversion features a few rods and a new bolt. It definitely had an economic possibility, especially if it were ever actually implemented on a large scale, but it seems the rifles just weren’t capable of being functionally altered.

Each “solution” only bred more problems. You needed a catch to ensure the thumb wouldn’t get caught in the reciprocating bolt, extra shielding to ensure the bolt wouldn’t fracture and fly into the user’s face, etc. The manual of arms gets very complicated to outright dangerous in battle conditions. I’m honestly surprised the Swiss and Austrians didn’t take advantage of their straight pull designs however, they seemed more naturally configured for conversion, only requiring a dust shield for the rear and some stock alterations.

i want to see hi speed footage of this gun being fired

I don’t know of any Rieders out there (outside of South Africa), but there are a couple Howells in the US, and some reproduction Charltons floating around. I have hope that I will be able to shoot one of them (on film) some day!

There is definitely one at the South African WWI memorial at Delville Wood, France – I visited and took some photos a while back. It reminds me very much of the Ekins automatic rifle.

http://firearms.96.lt/pages/Rieder%20Rifle.png

Jerry Miculek’s youtube channel has a short video about a conversion on a 1903 Springfield:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IVNQQplAzu0&list=UUhk5eyAGuO3J4rV-CiMNkNQ

The gap between 18 June 1941 and 10 October 1944 is huge. Why?

Yeah, it took me a minute to figure that one out too. It could be written better – 1944 is when they gave a completed rifle back to Rieder (the program presumably being determined to be unnecessary by then), not when he delivered the converted guns to the military.

The Rieder (or Reider?- spellings differ) follows the pattern of most “auto conversions” of bolt rifles of the time. They usually had a long piston-rod assembly on the right side of the stock (there really being nowhere else to put it), plus some sort of cam at the end to turn the bolt. Most also had a bolted-on “pistol grip” which had to be used to get the shooter’s hand down out of the way of the reciprocating piston-rod assembly, which was usually perfectly placed to amputate your thumb.

During WW1, Enfield made up at least one experimental article on an SMLE No. 1 Mk III. Called the “Sword Guard” pattern due to the shape of its stamped cam-piece, it closely resembled both this one and the Australian Charlton.

WF Bern did a similar one on a K31 straight-pull sometime in the late 1930s. It just needed a piston unit, as of course the K31 already has a built-in cam path device to achieve the straight-pull “effect” on what is actually a turn-bolt action.

What all such conversions have in common is that they are too heavy and generally unbalanced to make practical combat rifles. Also, due to their light bolt weight and lack of interchangeable barrels, they have a high enough ROF to be difficult to control and suffer from excessive barrel heating, the only cure for which is to stop firing and let the barrel cool, which rather defeats their purpose.

As ingenious as these conversions are, and as much as one must respect their designers’ inspiration, I suspect the main reason none of them got past the prototype stage is that even in a “backs to the wall” situation, the Ordnance departments realized that building proper LMGs/GPMGs from the ground up was a better course in the long run, as far as logistics and production went.

It has occurred to me that in Australia and South Africa, a “reverse-engineered” copy of the Japanese Type 96 or 99 LMG chambered for 0.303in would have been highly interesting. In spite of their Bren-like looks, they’re based on the Hotchkiss system, not the ZB, according to Chinn.

Since the Japanese Navy’s version of the 7.7mm round was basically a copy of the 0.303in Enfield, including the rim, welll…

cheers

eon

The “Sword Guard” rifle you are thinking of is the Howell – designed during WWI and investigated further during WWII as a possible weapon for the British Home Guard. Another WWI-era automatic SMLE conversion was the Dawson & Buckingham rifle.

The spelling is definitely Rieder.

In regards to if this was more wasteful than just making more Sten guns or Bren guns, keep in mind this was South Africa. Did South Africa have an arms industry at the time capable of making a military arm from the ground up? While Gun drills and rifling machines would have been uncommon, South Africa would have had a good number of machine shops to support steam engines, automobiles, agricultural equipment, etc. Such shops could make these parts. So reusing the Enfield receiver and barrel made sense, especially as they were already properly heat treated, which could be an issue for small shops. As a poor-man’s Bren gun it was worth looking into. As a mainly South African, as opposed to a purely British, effort it makes some sense. Of course South Africa was commonwealth back then, etc., but from the text above it looks like it was more of a local project.

Incidentally, John Browning’s first machine gun was a converted lever action hunting rifle. The design concept from that was carried over to the Colt “potato digger.” A case where the improvised conversion design led to a production weapon.

And the Turkish Army (which had a lot of Winchester lever actions they’d bought for their war with Russia in the 1870s) used Browning’s original “spring buttplate” system to convert those lever guns to short-range semiauto weapons in the early 20th Century. They were still .44 rimfires, but were apparently intended as weapons for short-range, massed fire against human-wave assaults as at Plevna in 1877.

The Turks had military observers at Port Arthur in the Russo-Japanese War, and saw what happened there basically as Plevna all over again. Just as the Winchesters had given them firepower superiority over the single-shot rifles of the Russians in 1877, they were looking for an edge over the Russians’ Mosin-Nagant bolt-actions in event of another go-round.

Of course they also bought machine guns, notably from the Germans, and in the end those proved to be a more practical solution.

cheers

eon

See our S.A.I.S. #13 -Special Service Lee-Enfields for details on the suppressed and autoloading SMLE conversions.

Go to http://www.skennerton.com/sais.html

Ian

And for a review of that book, you need look no farther than here:

https://www.forgottenweapons.com/book-review-special-service-lee-enfields/

Henry Rieder is my grandfather, although I never got to meet him. My father still remembers him ‘playing’ with the rifle.

As a family my father and I visited Delville Wood in 2013, and to the South African War Museum. Much to our surprise, the rifle is now being displayed there, and no longer at the Military Museum The Castle. The link is here http://www.delvillewood.com/rieders2.htm

I went to the War Museum in joburg last saturday, and tried to find the display of the Rieder rifle, but it seems to be locked up in storage, which is very sad. The people working there also had no idea what I was talking about when I asked them about it.

My name is Brian Rieder born 1945, son of Walter Rieder born 1920, son of Joseph Rieder born late 1800’s? Strange as it may seem, my father also worked at the Post Office in Port Elizabeth as a teleprinter technician. During the 2nd world war he also served in the signals division doing duty in the North Africa campaign escaping from Tobruk during it’s siege then posted to Italy. He took a keen interest in gunsmithing which he persued into his seventies. So close, yet so far apart. I wonder if there was any relationship far back in time.

Brian Rieder please contact me on Facebook Messenger. Henry Rieder was my father-in-law.

Hi Jean, I am responding to your request as at 1 August 2020. Regards, Another Rieder, Brian.

Hi Brian, thanks for your prompt reply. Are you on Facebook? If so search my name and message me in Messenger. Maybe we can see if you have a connection to my husband’s side of the Rieder family!

Jean Louw Rieder

Hi Brian, thanks for your prompt reply. Maybe we can see if you have a connection to my husband’s side of the Rieder family! Look for me on Facebook and inbox me.

Jean Louw Rieder

Hi Brian, email me at jean.rieder@gmail.com. Jean