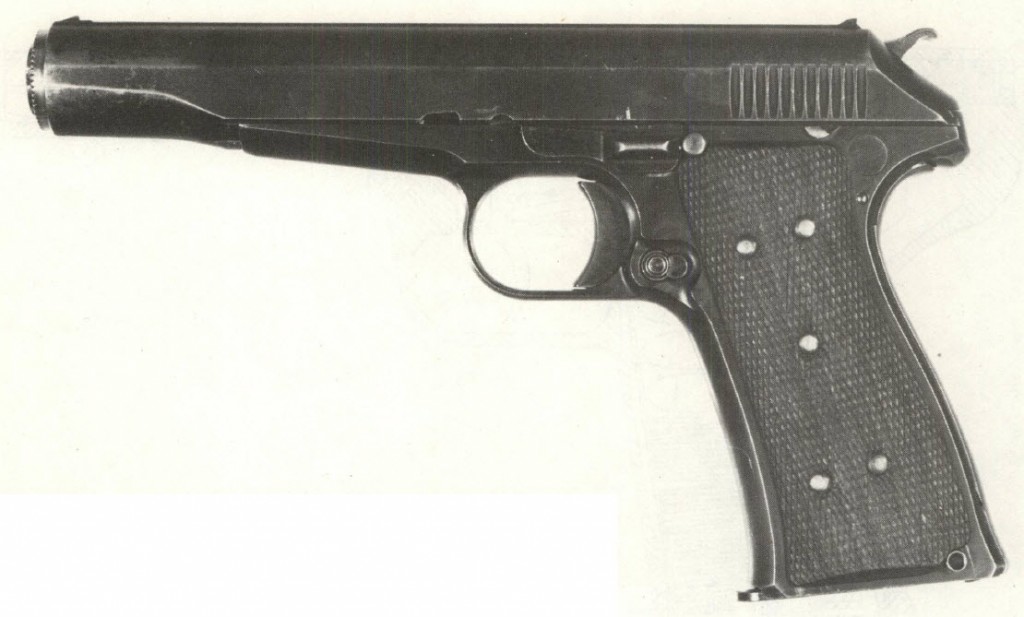

With the announcement of Remington’s reintroduction of the classic Model 51 as the new Remington R51, I have had several people ask for information on the forgotten stepchild of the Model 51, the M53. I haven’t had a chance to handle or shoot one of these myself (and may never have the chance, since only one or two still exist), so this will be more a recap of the existing information on the gun rather than a new firsthand perspective. If anyone from Remington happens to be reading this, they should absolutely consider introducing a modern .45 caliber R53 to go along with the R51! But I digress…

The M53, also sometimes known as the Remington Model 1917 (and easily confused with the several other Model 1917 firearms in US inventory), was designed by John D. Pedersen during World War I. As mentioned above, the gun was an offshoot of the Model 51 civilian pistol, and was actually produced prior to the commercial introduction of that gun. Remington was hoping for a military contract, and suggested its new Pedersen design in .45ACP to the US Army in place of the fairly newly-adopted Colt/Browning M1911. The Army responded that they would test the pistol if Remingtonwould send them one, but also placed and order for 150,000 M1911 pistol to be made by Remington. I suspect that Remington management took the position of, why bother working all the bugs out of a new design when they could clearly get large orders for an already-proven pistol in the 1911 – and the company dropped its attempts to sell Pedersen’s design to the Army.

However, on April 4th 1918 a group of Marine and Navy officers paid a visit to Remington, and indicated an interest in the M53. The Navy (and its subsidiary, the Marine Corps) was having trouble procuring enough 1911 pistols to meet its needs, and was interested in adopting its own design to avoid competing with the Army for supply. This may seem crazy by today’s standards, but it was not an uncommon situation at the time. The Navy had gone so far as to adopt its own proprietary cartridge 20 years earlier, in the .236 Lee Navy, and the inter-service rivalry for arms production was a common issue into WWII in other nations (the Type I Carcano for the Japanese Imperial Navy, the Luftwaffe FG-42, etc).

Anyway, Remington was happy to oblige and the Navy was provided an M53 pistol to test, which they did with remarkable haste.The testing took place on June 4th and 5th of 1918, and it included a 5,000-round endurance test, sand test, accuracy test, and 34 other tests or examinations. All of this was done in a competitive format, with the Grant-Hammond as the other potential new Navy pistol and the Colt 1911 as the control. We will cover the Grant-Hammond in more depth in a later article, but I will include its results for comparison here.

The Tests

The first four tests were demonstration of function and disassembly of the pistol by a Remington factory rep, for familiarization of the testing board. Tests 5-9 were counts of the number of parts, springs, and pins in each gun:

| # of parts: | Grant-Hammond | Remington M53 | Colt 1911 |

| Coil springs | 16 | 3 | 5 |

| Flat springs | — | — | 1 |

| Pins | 16 | 8 | 7 |

| General parts | 36 | 47 (27) | 35 |

| Screws | 2 | — | 4 |

The caveat there is that the Remington grip panels were permanent assemblies of 11 parts each (5 rivets, 3 studs, two stiffening plates, and a grip panel) that were not intended to be disassembled. Taking that into account, the Remington was definitely the simplest of the contenders. And as a side note, 16 coil springs in the Grant-Hammond? Jeez!

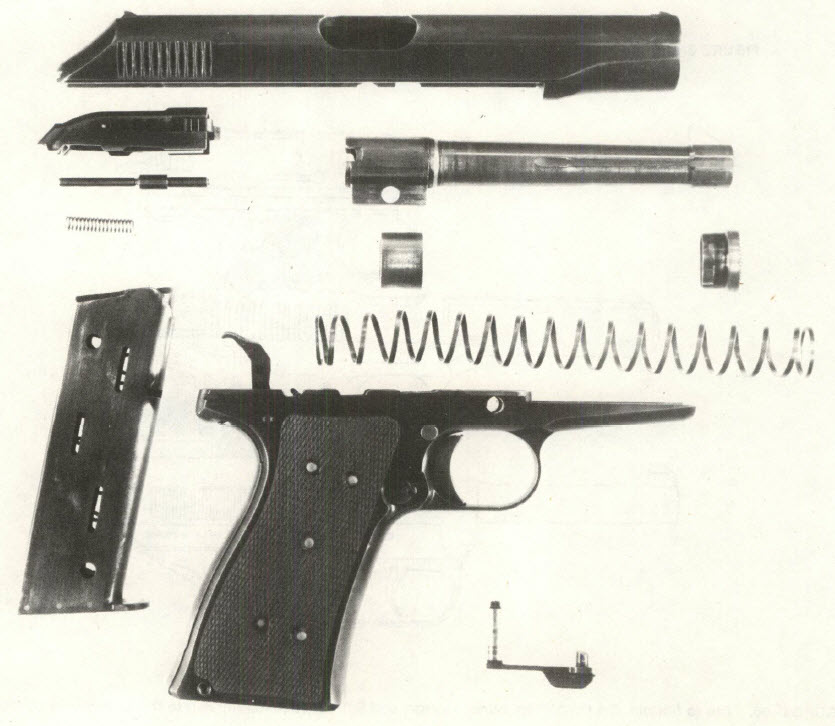

Test 10 was a detailed description of the pistols, which can be found as the “technical specs” section at the end of this article. Test 11 was whether all the parts were interchangeable between different guns (ie, no hand fitting required), which on the Remington they were. The next tests were of disassembly and reassembly time:

| Field strip | Field reassembly | Detail strip | Detail reassembly | |

| Remington M53 | 25 sec | 43 sec | 1 min 7 sec | 2 min 31 sec |

| Grant-Hammond | 20 sec | (not recorded) | 8 min 12 sec | 22 min 30 sec |

No figures were recorded for the Colt, but the M53 is clearly the winner here. Those 16 springs in the Grant-Hammond must have really taken a toll here. The Grant-Hammond required a whole selection tools for this test, while the Colt required a screwdriver and the Remington required no tools at all.

After the factory reps fired each pistol for demonstration, the testing board’s members fired the guns for accuracy:

| Grant-Hammond | Remington M53 | Colt 1911 (fired from a rest) |

|

| 25 yards, prone | 0.79″ | 2.25″ | 0.86″ |

| 25 yards, offhand | 2.95″ | 2.32″ | — |

| 50 yards, offhand | 3.80″ | 5.72″ | 1.36″ |

The board did note that the Colt and Grant-Hammond pistols were basically new, while the M53 used for this trial was pretty well worn, having seen about 6,250 rounds fired prior to the Navy trial. This accounted for its less impressive accuracy scores, and also for the slightly lower muzzle velocity it exhibited compared to the other pistols. In rapid fire, the M53 obliterated the Grant-Hammond, firing 21 rounds (3 mags) in 18 seconds compared to the G-H’s 24 rounds (3 mags) in 38 seconds.

Another test compared time to replace parts, and the M53 won this by a wide margin as well, requiring a third the time to replace the firing pin and extractor. The barrel and ejector were also subject to this test, but on the G-H those parts were built into permanent assemblies. When the extractors were removed from the guns to test them as single-shot arms, the Remington failed to eject 4 or 5 rounds, and the G-H failed on 3 of 5. However, the M53 had no trouble digesting cartridges with very thin primers (intended to be pierced for testing) nor the pair of 25% overpressure or pair of 25% underpressure cartridges. It also ran flawlessly when tested in horizontal and upside-down firing positions.

Next up for the M53 was a 5,000-round endurance test, with the factory reps allowed to clean and lubricate the guns at their digression. The Remington M53 finished this challenge with a total of 25 stoppages. Of these, 8 were failures to lock open which were attributed to a defective magazine (removed from the test after 1200 rounds). A further 14 were attributed to faulty cartridges, leaving just 3 problems with the pistol itself. There were a broken hammer at 975 rounds (not counting the 6k+ already fired through the gun previously), a piece of grip falling under the trigger and causing a failure to fire, and a corner of the slide chipping off and locking the slide open. Not bad! The Grand-Hammond suffered 89 stoppages (not counting bad ammo), for comparison. The Colt 1911, after eliminating magazine faults and bad ammo, suffered 3 broken barrel bushings.

The sand test involved plugging the barrel and inserted a loaded magazine before burying the pistols in sand. Testers were then allowed to clear sand by shaking or wiping by hand before shooting. The M53 fairly to eject once, and its slide didn’t lock open during this test, but it was otherwise satisfactory. This is particularly impressive given the board’s note that the broken corner of the slide form the endurance test allowed much more sand into the gun than would normally have been possible.

It should come as no surprise that the Navy conclusion was that the Remington M53 was “…a simple, rugged and entirely dependable weapon, which should be suitable in every respect for a service pistol” and requested a bid for 75,000 of them (which would have replaced all the 1911s and revolvers in Naval and Marine Corps service). Remington submitted the bid on June 21, 1918 (a mere 2 months after the initial interest from the Navy). That was deemed to expensive, and a second bid was submitted shortly thereafter, on July 5th, 1918. Unfortunately for Remington, the price they were hoping for was more than the Navy could justify, especially as the end of the war became more likely. The contract would have been a cost-plus basis, and Remington’s revised lower quote came to $9.93 per gun just for the tooling and profit, not including labor and materials. At this time a 1911 was costing the government about $15 – the M53 would have been significantly more expensive. As the war ended, the Navy dropped the issue, and Remington turned to tooling up for commercial production of the smaller-caliber Model 51. Only one M53 is known to remain today, in Remington’s museum. A second is believed to have gotten into private hands in 1933 or 34, and it’s fate has been unknown since at least the 60s.

The Army did test the pistol in 1920, and seems have come away with a favorable opinion, but by that time the 1911 was firmly entrenched as the military standard sidearm, and nothing more came of the M53.

The civilian Model 51 featured a concealed hammer, grip safety, thumb safety, and magazine safety. To meet military preferences, the M53 used a hammer with an exposed spur – snagging the hammer on concealment garments wasn’t a military concern, and the exposed hammer would allow manual recocking if a round failed to fire. The M53 also eliminated the thumb safety and pinned the grip safety in place, at Navy request (more on the justification for this request in a few days).

The mechanism of the M53 (and also the Model 51) was somewhat unusual, as it had to avoid infringing on Browning’s patents covering features like the single unitized slide and breechblock. Pedersen did this by devising a system in which the slide housed an independent breechblock. Then the pistol fired, the slide and breech would recoil together for a distance of approximately 2mm (1/12th of an inch), at which point the breechblock would lock against a lug in the pistol’s frame. Inertia would force the slide to continue rearward, and after a bit more travel a cammed track in the slide would lift the breechblock up and out of its locked position. The slide and breechblock would then continue the remainder of the way back, ejecting the spent case and then loading a fresh round form the magazine. This system is often misunderstood as being blowback, since the Model 51 is chambered for the .380ACP cartridge and has a fixed barrel (a feature generally associated with blowback pistols).

This mechanism actually had fewer moving parts than Browning’s 1911, had a fixed barrel for better potential accuracy, less felt recoil than the 1911, and weighed less. Had the M53 been present in the original trials for Army pistols in 1907-1910, I suspect it would have beaten out the Browning design. The Model 51 has always been an acknowledged favorite of pistol cognoscenti, and it would be fascinating to how formal US adoption could have done to evolve the M53.

Technical Specs

Action: Hesitation lock (fixed barrel)

Caliber: .45 ACP

Overall length: 8.25 in (210 mm)

Barrel length: 5 in (127 mm)

Weight (with empty magazine): 2lb 3 oz (907 g)

Magazine capacity: 7 rounds

Rifling: 1:16″ twist

References

Buffaloe, Ed. Unblinking Eye: Remington 51

Ezell, Edward C. Handguns of the World. Stackpole Books, New York, 1981.

Walker, Charles. “The Remington M53 Pistol, Cal .45, M1918, USN (almost)”. Gun Report magazine, October 1969.

i was able to handle and dry fire the new m 51 at a trade show earlier this week, it was very small and felt pretty good in the hand, the trigger wasn’t bad. i would like to see a full sized version and definitely a .45 version.

I’ve already emailed Remington, begging for a .45 version of the R51. Keep it small like the 9mm and it will sell like crazy. Even though 9mm isn’t a great favorite of mine, I still look forward to handling the R51 at the upcoming Great American Outdoor Show.

The most detail of how-it-work description is a Pedersen patent, but warning: this is VERY detailed. The patent explains the Remington Model 51. This patent is US 1,348,733. You can read it here:

http://pdfpiw.uspto.gov/.piw?Docid=01348733&homeurl=http%3A%2F%2Fpatft.uspto.gov%2Fnetacgi%2Fnph-Parser%3FSect1%3DPTO1%2526Sect2%3DHITOFF%2526d%3DPALL%2526p%3D1%2526u%3D%25252Fnetahtml%25252FPTO%25252Fsrchnum.htm%2526r%3D1%2526f%3DG%2526l%3D50%2526s1%3D1348733.PN.%2526OS%3DPN%2F1348733%2526RS%3DPN%2F1348733&PageNum=&Rtype=&SectionNum=&idkey=NONE&Input=View+first+page

what VERY detailed mean? 19 sheets of drawings and 262 patent claims (for comparasion Browning’s patent for 1911 – US 984514 A has only 3 sheets of drawings and 34 patent claims).

The “hesitation lock” sounds like a form of delayed blow-back rather than recoil. If I understand it correctly the initial impetus is blow-back for a travel of 2mm, with the continued movement of the slide providing the delay before final unlocking.

Yeah, it is a bit of a hybrid system – I would guess the rationale was to avoid patent infringement.

If you think about it, it’s gas operated. The cartridge case is a gas piston, the breech block serves the function of an op-rod in that it transmits energy to the bolt carrier (slide)while staying locked (like a bolt with a bit of excessive headspace). After the appropriate travel, the bolt carrier (slide) unlocks the bolt and carries it open.

The lock delay does allow for a considerably lighter slide for a given power cartridge. Compare the slide of a Colt Pocket Hammerless to the slide of the original model 51.

That’s quite an intuitive way to think about it.

Thank you so much for those pictures! I need something to drool over, as there are only two other pics of the gun that I’m aware of: http://i.imgur.com/2HtW3wc.png

picture is gone, reupload?

http://imgur.com/a/bDx3W

It’s got the good looks of it’s little brother and a more potent bite. Too bad they didn’t go into production.

Slick design, the fixed barrel being definitely plus. Now, let’s look at not so pleasing part of it: it locks (temporarily but still does) into frame. Thus frame better be metal, preferably steel. With large capacity mag and corresponding frame construction as you would expect from service pistol, it will wind up – too heavy. Lets look what CZ have done recently with their pistols P7 and P9, since original steel frame guns were too heavy – went to plastic. Can same be done with Remington? And how?

Personally, I’d rather have steel. The weight helps control recoil, and I don’t mind carrying it.

Absolutely. The fascination with ultra-light high-powered pistols only appeals to those who know even less physics than I do, or do not practice with their guns on a regular basis. It only took one +P .38 through an airweight J-frame Smith to remind me of the joys of heavy steel. Probably the best mix of power and small size I have any extensive experience with is a 9mm Star Starfire (don’t laugh: after a 200 round breakin it was solid reliable with ammo it liked) which was just flat fun to plink with, unlike plastic 9s the same size.

Another steel classic I would love to see updated: please, Poland, get Radom to bring back the 1935. As much like the original as possible, except in .45 with an ambidex safety.

I believe Radom did an extremely limited production run of Vis. 35 in the early 90s. They were more expensive than the originals IIRC. I too, would love to see a full return of the under appreciated firearm.

I’ve seen one of the sample test guns from Radom, but I don’t think they made more than a handful – not an actual production run. From speaking to them at SHOT last year, it sounds like the factory managers want a commitment from a buyer for a large order before they really tool up, and all the potential clients want to wait to commit until they see the factory successfully tooled up and in production. It’s a Catch-22.

Hi Jim

what would you consider reasonable compromise weight for semi-auto? Grams or ounces, I don’t care. In my view 600-700g hi-cap sounds about right. I am talking service, open carry piece.

It all depends what you do with it. Try to lug 1.1-1.2 kg weight plus ammo on your hip whole day long. But yes, I understand CZs have done some fame for themselves with steel frames, exactly for reason as you say.

I have for years. All-steel 1911’s, S&W 5900-series, S&W N-frame revolvers with barrels of 2.75-4 inches. Many have been carried inside the belt.

Ditto here on the preference for a steel frame. I have, for years, been reading comments on “The High Road” and other forums, where people refer to any non-polymer frame gun as a “boat anchor” and complain how it’s “too heavy to lug around all day.” I can only shake my head at such comments. I have also, for years, carried all steel handguns around all day, every day, and I truly don’t even notice the weight. A good belt and properly designed holster and you truly do not even notice once you get used to carrying. You’d think these people were humping 100 pound rucksacks around all day by the comments they make (something else I’ve done, BTW). And as a result of this attitude you get these featherweight guns like the scandium revolvers S&W makes — something I’m convinced people must spend almost no time at the range with. I shot one once, an S&W loaded with .38spl +P, and I found it distinctly unpleasant — and bear in mind the gun was actually chambered for .357 magnum; I have no desire to shoot one loaded with full power magnum loads. I think they’re a bad idea. Guns that are physically punishing to shoot won’t get shot. People won’t practice with them, and will not learn to control them in realistic strings of fire.

This new Remington won’t be that much of a handful, but a steel frame would doubtless make it nicer to shoot. Notice also that Colt introduced the Commander with an alloy frame, but today only make it with a steel frame. I think there is a market for an all steel gun. Perhaps Remington will follow Colt’s example in this at least, and one day introduce an all steel version. I also hope to see a .45 version, and it would really nice if they’d make not only a compact one, but a full-size one like the Model 53.

Considering how long the all steel M1911 remained in service that seems like a bit of a no-issue.

One of the problems that has plagued the original Model 51 has been cracked breechblocks. Whatever the cause of this problem, I hope it has been corrected on the new R51.

I’d buy one in .45. Keep it single stack and slim! The new M51 is on my wish list and one in .45 that keeps the original lines would be a must buy for me.

Yeah, the most disappointing ting to me with regards to the new iteration is the ‘modernized’ look. The old guns had class, why does everything have to be edgy and tactical?

I couldn’t agree with you more, Ian.

It seems the success of retro 1911’s (and copies thereof), SAA style revolvers (and copies thereof), Winchester lever actions (and copies thereof), etc, would indicate to companies that much-loved discontinued models of yesteryear are easy sells in a market hungry for historical styled arms, where availability and shoot-ability of the originals is rapidly waning.

Perhaps it’s not too late to hope Remington…or SOMEONE… Will resurrect the M51,and/or the M53 in its original form.

(Hey Colt…this same argument applies to your .32/.380 models of 1903 and 1908!!!)

Wait, the firearms production should be started one-by-one not all in one time. Additionally I think that is better to produce “one firearm in each category” than “all firearms in one category”. Nowadays Remington produce auto-loading pistol, shotguns, full-power cartridge (i.e. level power similar to .30-06) rifles, .223 rifles but not revolver-cartridge rifles. I think Remington should fill this gap in their offer. For example with improved Remington Model 25 pump-action rifle, maybe rechambered in .38 Special – .357 Magnum? (shooting both .38 Special and .357 Magnum without adjusting as .22 rimfire Remington Model 121 can shoot .22 Short, .22 Long and .22 Long rifle).

in most polymer frame pistols there is some locking force applied to the frame, glock, fns 9, fn 57, hk usp, beretta px4 etc, all of which have a steel insert which seems relatively problem free. even cz has a version of the 85 with polymer frame, i’m with ian though, the weight is good for that 2nd shot.

You mean ‘un-locking’ force, I’d think….. not catching on words, just trying to be technically correct.

Great write up, Ian!

This is probably the handgun I’m saddest about not being able to have… Or even look at… So thanks again.

Remington Model 51 probably is most protected design by patents, over 30, and most

not been used on production guns. They included grip safeties with main springs

directing exertion of force on impact member from uncocked to cocked position which

used decades after by HK P7 pistols.

Hesitating blowback uses an initial free blowback stage which is not lesser than 2mm

remaining in standart lock out distance for the rounds it uses. That is, hesitating

stage following that initial blowback begins at just time on when its need ends and

in addition, recoiling masses are not greater than simple blowback counterparts.

Therefore, on initial recoiling stage, felt recoil should be equal to standart

simple blowback kinds. But, hesitating stage slows the recoiling masses speed and

reduces the felt recoil as spreading its effect into the time with a plus effect

that, the slide and engaged breechbolt will not beat the receiver at returning home

like other examples using powerfull return springs for this purpose.

Since .32″ACP and .380″ACP are rounds usable safely in simple blowback system, the

hesitating lock may not be necessary, but powerfull .45″ACP and 9mm Parabellum kinds

backgardens are not this large to play in. Therefore, hesitating approach should be

usable. Besides, the initial free blowback distance can be held lesser than the

actual size but, it should be kept all clean and tidy free from fouls and dirt all

the time to start the initial slide movement to start the unlocking stage or in the

other case the pistol will not work. Therefore, at least of 2mm free blowback is

necessary. From the photos Ian kindly offered, it seems that, the round case sits

fully supported within the chamber and even the extractor front tip cammed off from

chamber inside wall like the way used in .22″RF and standart magazine shotgun

barrels. This will give a safe margin for free blowback not lesser than 4mm and this

will comfortably enough for starting the initial slide movement in all terms.

Hesitating lock and low barrel axis combinely reduces the felt recoil with a rather

weak return spring and The Model 53 seems perfectly usable. But in NewR51 using 9mm

the situation is slightly different since the rather conical case this round uses,

there should be some gas leaks to the backward from the chamber and the holes

looking upside on top of slide may be provided for that purpose.

Model 53 has not any safety and this reduces the number of parts and on a service

pistol at least one is necessary.

Besides, the number of parts do not reflect the simplicity of a construction, the

form and manufacuring them shold also be counted and also the way their mounting.

As known, breechblock of both Model 51 and 53 keeps its location in battery on mode

by the presence of barrel and dismounting the same will free that part. On model 51

achieving this is rather difficult but on Model 53, it seems that a dismountable

collar like FN1910 is provided for easy barrel take out. Not using this on Model 51

production is also questionable.

On the other hand, at field stripping a vital member being small and easily lost

like a firing pin should not be wranglered around. This is very important at the

field and combat situations. This presence for old models seems corrected on NewR51.

Metal frames are good but, how long it can be survived on current manufacturing costs rising trend. It is nearly certain that, The New R51 will be changed to plastics after an expected purchaser amount is provided.

Remington deserves applauses as bringing a new breath on handgun field rather than

all known examples of tilted barrel types even if being a rebirth of a concept

dating nearly a hundred years ago. Congratulations.

“9mm Parabellum”

Note: the new Remington R51 is NOT first Pedersen-action firearm to utilize this method. The 9mm Parabellum was earlier in SIG MKMS submachine-gun.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SIG_MKMS

(this gun was also chambered in 9x25mm Mauser Export)

Is “method”, should be “method and firing 9x19mm ammo”

I think that form of “hesitation lock”

where a two part bolt blows back for a short distance before the actual bolt hits a rigid locking surface, and the bolt carrier continues freely, providing a delay, before pulling the actual bolt out of the locking surfaces…

-was used in some Browning designs around 1900.

Alsop and Popelinski, say that the system fell from favour because of the dificulty of maintaining the consistent short distance for the initial blowback phase. Get it too short and there is insufficeint momentum given to the bolt carrier, too long (either through loose manufacture or wear) and cases start bulging, too much speed and momentum is transfered to the bolt carrier, resulting in insfficeint delay, and further attrition on the gun.

Despite that objection, Benelli also appears to use a variant of that system on a 9mmP pistol, and it has a good reputation.

Btw, when did Remington leave the semi-automatic pistol market in the first place?

As with a lot of great guns, it was the Great Depression. Production technically ended in 1927, but I suspect Remington made the “final” run thinking that their stock would run out after two or three years and then they would make some more. Alas, the economy interfered.

After the Model 51 production ended in 1927, the only handgun Remington would make was the XP100, which is really a rifle cut down. They introduced a 1911 in 2010, and then the R51 this year. They’ve been out of the market for a long time!

Does anyone know if the .40 cal BSA pistol from the 1920s was also a Pedersen design?

Kieth could you tell more about the BSA pistol and the .40 cal ammo it shot? I am not familiar with it. Thanks Bob

Going from a photo of the pistol’s right side on page 104 of Ian V Hogg’s “illustrated encyclopedia of firearms” superficially it looked very similar to the Rem mod 53,

In detail however, its solid looking trigger appears to pivot, the bore line appears to be even lower in the hand than the 53, there is what appears to be knurling on the muzzle end of the barrel- or barrel bushing.

The grip angle is slightly more raked, and the front strap straighter and the backstrap more curved than the 53. Both lack obvious grip screws.

The base of the grips on the BSA is cut away to allow better grip for mag changes, and there appears to be a heal mag release (not sure on that)

The slide is superficially similar, but has deep cuts taken out at the rear end, and these are serrated at the rear to form a very positive grip for cycling the slide. It’s difficult to see, but the hammer appears to be concealed.

Interestingly, the extractor appears to be mounted (with a vertical pivot pin) to the slide itself, thus precluding the separate breech bolt which the Remington uses as part of its (pedersen) delay mechanism. The extractor also fits into a slot in the breech end of the barrel – precluding the use of a rotating barrel locking system…

bloody thing could be straight blow back!

The only info which Hogg gives in addition to the picture, is it was announced in 1919 (straight after “the war to end all wars(tm)” so hardly an opportune moment to market a new military pistol)intended for military service, chambered for a .40″ round and, due to lack of any military interest, was never put into production.

I’ve searched for patents, but never found anything.

It’s a very compact, very modern looking pistol, way before its time, and in a calibre half a century or more before its time.

“calibre”

Have you any ballistic data? If you don’t know basic ballistic data (true* bullet diameter AND bullet weight AND muzzle velocity) you can’t say round “x” is better than round “y”.

*for example for .38 Super the true bullet diameter is .356

No, I have no firm info about round beyond the claimed .40″ diameter.

I have seen comments about and photographs of a .39″ belted head pistol case by BSA, but I have no idea whether that is the round for pistol which Hogg shows.

There may be a separate breechbolt backed up a powerfull

spring within the slide and initial blowback action

begins with sole recoiling of that member to the lock

shoulder for hesitating stage. Recoiling slide with the

pinned extractor will catch the empty case in front of

the breechbolt.

“The Army did test the pistol in 1920, and seems have come away with a favorable opinion, but by that time the 1911 was firmly entrenched as the military standard sidearm, and nothing more came of the M53.”

Yep, good old Army. “Who cares that something better’s come along, we’ve gotta stick with what we’ve already got.” The 1911 is a fine pistol, but the Remington 53 seems to have done everything the 1911 could, better.

There’s a lot more to such decisions than which weapon is “better.” IF the Model 53 truly proved to be better than the 1911, which is doubtful, the difference would have been minimal. In no way could the minor improvements noted in Ian’s article offset the Remington’s increased cost nor the need for an entirely new supply of spare parts, magazines and holsters. You also need new training and maintenance manuals. In a cash strapped, Depression-era military there was no way this would happen.

That last sentence should actually read “post-war era military.” Wow, what a disconnect between brain and finger!

Kieth. Thank you for your reply

I think,

Hesitation lock needs; a breechbolt to go locked and

a carrier or slide to unlock the former by a start

effect coming from the same. This may be an impact

or an exertion of compressed spring and should be

strong enough to start the unlocking motion and the

distance needed should be enough to obtain sufficient momentum and gap remaining all the time at necessary

value against to all fouling and wearing effects.

Benelli can not be classified in “Hesitating Lock”,

and be counted in true “Locked Breech”, since the

member which subject to counter the initial recoil

force through the case is already locked onto the

receiver and the carrier member, slide, presses down

the same through inertia as retaining ıts location

at instant of highest pressure still being present

within the chamber. When the forward inertial thrust

of slide gets weakened against to the rearward momentum

through the decreased chamber pressure, the slide begins

to go rearward as actuating the connected toggle and by

means, gets the breechbolt out of locking recess cut on

the receiver to let it unloading and loading processes.

There is neither initial blowback gap nor a free,

unlocked recoiling breechblock on that construction.

Was there any more information about the Navy’s request to disable the safeties? You said “more on the justification for this request in a few days” but I don’t see any more info on the site

i don’t know but i started having a filling that dell mouse are much better then any other, since the era of optical mouse has began, this mouse last at most for 15 months, i just have a habit of trying new product every time and i come across this one & seriously Dell MS111 as last for more then 2 years

And once again our military is looking for a new sidearm. Wonder if Remington missed the boat again? Can’t help but wonder what a .40 S&W double stack 12 rd capacity Mod 53 would be like and compair with modern competition?