Two things today…

First up, I recently had a chance to tinker with a rifle made by Brethren Arms, which is in many ways the modern evolution of the StG-45 that we looked at in slow motion yesterday. They call it the BA-300, and it’s a basically an MP5 or HK53 in .300 Blackout. A very compact rifle using the roller-delayed blowback system pioneered in Mauser’s StG-45, coupled with a cartridge that is a ballistic virtual twin of the 8mm Kurz (both cartridges fire a 125 grain bullet at 2200-2250 fps). With a 9-inch barrel and suppressor, the BA300 was an absolute buttercup to shoot, even in full auto. Brethren does a great job making them, and includes some nice updates like a welded-on rail for optics and a properly-placed ambidextrous magazine release.

One of the best parts of the range trip for me was listening to Quinn talk about his guns. He is a rare combination of whip-smart engineer and experienced military veteran, and he has no illusions about the shortcomings of the H&K design (unreachable safety and mag release, awkward charging handle, heavy trigger, etc). Rather than try to defend those elements with some huffing and puffing about Teutonic infallibility, he looks at the shortcomings as opportunities to improve the guns. I think Lossnitzer and Maier would be thrilled to see their rifle still being the subject of improvements 70 years after they built the first versions of it. Anyway, you can see the full video that Karl and I did with him over at Full30:

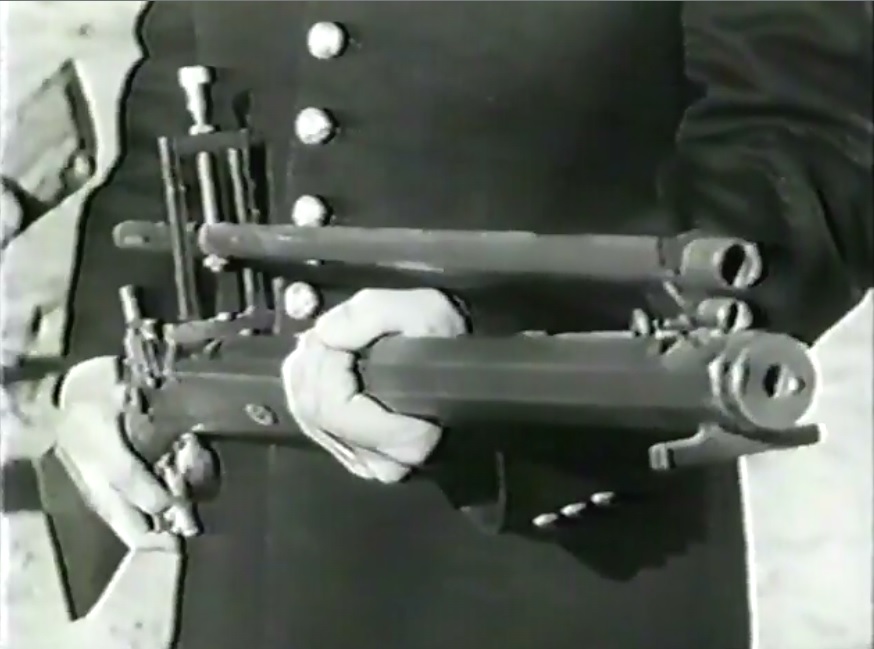

Changing gears completely, the other gun I would like to touch on today is a super-heavy target rifle dating back to the Civil War. Weighing in at 37 pounds, it is a .68 caliber progressive-twist-rifled muzzleloader with an interestingly storied history. It is referenced in Charles Winthrop Taylor’s book Our Rifles on page 91. The story is that a Captain Metcalf in the Union Army used it in the Battle of Pleasant Hill in the Red River campaign of 1864 to snipe a Confederate general while he was shaving in the morning, as a range of 1 mile, 187 feet (1794 meters). This story came to the public notice when it was made into an episode of Jack Webb’s TV show “TRUE” in 1962.

The rifle allegedly has a 25x telescopic sight, and Metcalf used a surveyor’s transit to precisely measure the distance to the target, and calculate the bullet drop and flight time he would have to account for.

Well, it turns out that the whole story is bogus (this article does a good job of explaining the details). Neither Metcalf (allegedly a West Point graduate) not the Confederate General he allegedly shot actually existed, and the numbers quoted by Sawyer for bullet flight time and drop are wildly implausible. HOWEVER – the rifle itself is real and has been connected to the story since at least 1944 (when Sawyer’s book was published). Its most recent known location was hanging in a bar in rural Texas, complete with plaque commemorating the Metcalf story. The bar owner died, though, and the rifle disappeared into someone else’s hands.

A friend of mine is a very highly renowned forensic ballistics expert (you may have seen him in the video I published on an original Girandoni air rifle), and he has been very interested in this rifle ever since he saw the episode of TRUE about it. He would really love to have a chance to fire it and get an idea of it’s actual capabilities. He has a doppler radar unit for tracking bullets, which allows him to track velocity and calculate exact ballistic coefficients, and this rifle would be a fantastic experiment with that equipment.

So…if anyone happens to recognize this rifle and know it’s whereabouts, could you let me know? We would really like to speak to its owner!

He has a doppler radar unit for tracking bullets, which allows him to track velocity and calculate exact ballistic coefficients. That is not cool. That is ultra-super wicked cool.

So, if I gather it right…. this Brethren Arms is making a replica to original STG 45.

H&K’s development has brought this design to higher stage of engineering and manufacturability. My question is – why to bother? Unless historical retrace is the objective. I do not see any new contribution there.

That roller-lock design, one way or the other faded away anyway. It is due to say however, that IF I was 70 years ago on this path of development and lacking the knowledge which has become later common domain, I’d be certainly enthusiastic too.

A roller-lock is still about the cheapest rifle one could set up to build in a small workshop. At least in the US, in state built and home built rifles are desired now.

Plus, the .300 Blackout appears to be something that is the wave of the future in the US.

On that .300 Blk… I consider it like something which makes more sense in this case and would be my preference over 5.56 any time. With having that, the mentioned roller-lock may be more reliable (the shorter is the casing, the better).

I’ve often thought that the VGI-5 (or is it VG1-5? Seriously, I don’t know) gas-retarded blowback action would be a good choice for an easy-to-build “utility” semi-auto carbine. 7.62 x 39 would be a reasonable choice of caliber, as it could use AK ammunition and magazines.

The question is, of course, would an action like that stand up to sustained use with that cartridge.

cheers

eon

Exactly, gas delayed blow-back – coupled with less energetic cartridge; that would be my cup of tea. This may be something to pursue in future, given the existence of .300 BLK in (but not necessarily) sub-sonic form.

for the lazy visitors it would e helpful if you post a link to the full 30 video. More guys watching the commercial should not be a bad thing 🙂

OK, after a double check on the article, i noticed the picture was clickable…i assumed it would enlarge it, but it let me straight to the video.(leaving the comment anyway, maybe someone else is helped by it)

Was the supposed range of the really “long shot” 1 mile and 187 yards or 1 mile and 187 feet? Because the latter is actually about 1666 meters. Not that it’s truly important, but I just noticed the discrepancy.

It was 187 feet, plus one mile.

Texas is also home to another “mile” shot. At the Battle of Adobe Walls, Billy Smith is said to have shot a Commanche warrior off his horse at over a mile. This story is also interesting because one of the muleskinners present was Bat Masterson.

Correct – the distance was supposedly measured by an Army surveyor after the fight. Billy Dixon supposedly accomplished the shot with a borrowed .50 caliber Sharps because he didn’t think his .45 Sharps would get the job done. I’ve assumed this was done with a tang sight. There is a group of BP Sharps shooters who have recreated the shot. They apparently do this yearly now up in Montana I think. Dixon stated that his target was a group of Indians sitting on horseback. One fell off his horse following the shot but the body was not found. Adobe Walls 2 was an interesting fight.

Interesting to see a macro elevation adjustment screw on a scope mount for a black powder rifle. I had thought of making one for a Martini-Henry rifle as a period possible DMR.

That and a 12-pounder IWB conceal weapon.

Early in the Civil War, some sharpshooters used extremely heavy “double-rest” rifles. Most were underhammer types with Malcolm scopes and false-muzzles that weighed between 25-30 lbs. One example I saw weighed in at close to 50 lbs. These were generally one-off types built by individual gunsmiths and were originally used as long-range target rifles. When properly loaded through the false-muzzles with crosscut, paper patched bullets, they were (and still are) capable of amazing accuracy at long ranges. They were generally superseded by lighter, more portable rifles such as the Sharps and the Whitworth as the war progressed, as their massive length and weight made them suitable for use only from a fixed and prepared position, as they required both a muzzle and a buttstock rest, often fitted to a custom platform that doubled as a case lid. The cased rifles with their loading accessories usually required at least two men to transport, and often had to be transported by wagon if they were to be moved any distance. In that sense, they were more like small, precision artillery pieces than individual weapons. The rifle in the picture actually seems a bit small and portable compared to some of the more extreme examples of the type that I’ve run across, although they are quite rare in any size and configuration. Remember, the first sharpshooter regiments were formed from groups of competitive marksmen who brought their own target rifles to the front. Though accurate, their immense size and slow loading rendered them impractical on the battlefield, but woe to the poor man who found himself in the crosshairs of one of these behemoths with a trained marksman behind it. Though the rifle in the picture and the story behind it may be apocryphal, rifles of that type, and larger, were in use during the Civil War and were fully capable of taking out a target at a mile or more.

Ian,

You may want to contact the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association if you are interested in these types of rifles. They sponsor bench-rest matches and shooters do show up with these monsters. I’ve been out of the game for a while, now, but they may be able to put you in touch with someone who has one of these rifles that would be willing to let you and your friend try it out. I sold my Kendall in 1993 (to pay for grad school), and haven’t owned one since.

I was going to say what doc said. I saw an episode of Shooting USA on the outdoor channel just this week that was all about the muzzle loading rifle association and museum. They actually have contest with replicas of the heavy barreled snipers. I doubt they would have the same gun but odds are they have one like it and you never know one of their members could have that exact one.

25X sight? BS. The scope’s width is too small. Looks like a 1.5 or 2x scope to me.

Agreed. I’ve never heard of any telescopic rifle sight of that type and era that was above 2.5X magnification.

According to Jack Coggins is Arms and Equipment of the Civil War (1962), the magnification of the scopes was one of two factors limiting the range of sniper rifles of the era. The other thing was that even though rifles like the Whitworth with its hexagonal bore and fitted “ball” were extremely accurate out to their maximum range, they had no more velocity than the standard rifle muskets, and as such had similar trajectories and range limits.

According to F. C. Myatt in The Encyclopedia of 19th Century Firearms (1979), the trajectory tables for the .577in Snider infantry rifle (a breechloader but with roughly the ballistics of the original muzzleloader it was modified from) state that even with the rifle sighted for 800 yards,and “first catch” (the point at which it will hit an enemy soldier in the head) is 780 yards for cavalry and 790 yards for infantry, “first graze” (the point at which the bullet hits the ground) is still “only” 810 yards. Or IOW, with an 800-yard “zero”, the “dangerous space” in which you stood a chance of collecting the bullet is only 30 yards wide.

A .45 caliber 300-grain solid-base bullet departing at 1400 would have a velocity of 631 FPS and 173 inches of “drop” at 300 yards, according to the Lyman Black Powder Handbook (1975).

Put it all together, and I doubt there was any muzzle-loading rifle of the Civil War period, even a super-heavyweight target rifle, that was accurate at much beyond 800 to 900 yards. A hit at 1,822.33 “strikes” me as a fluke, if it ever happened at all.

On the other hand…

The MV of a .45 caliber blackpowder rifle with a heavyweight (two-piece) bullet such as snipers used would be in about the 1400-1450 FPS range assuming a maximum charge (about 80 to 90 grains). This would put it in the same ballistic class as the Sharps “Big Fifty” of a decade later, such as Billy Smith made his “one mile” shot with at Adobe Walls II.

As for that one-mile shot, the Sharps “Big Fifty” (the .50-90, as the .50-110 wasn’t introduced until 1880) had an MV of about 1350 with the usual 473-grain paper-patched lead bullet, or 1470 with the lighter 335-grain. (That was a long-range target bullet, not a buffalo-basher.) So, if the target was standing still for the roughly five seconds it would take for the decelerating bullet to get that far, he probably had a good chance of a hit assuming he used a lot of holdover, which with a tang sight he could probably do.

I’m not sure it could be done with a telescopic-sighted sniper muzzle-loader at a similar range, simply because of the restricted field of view of the scopes of that type. I.e., the shooter would be using so much holdover that the target would be out of the scope field.

Put it all together, and the Civil War shot more-or-less duplicated Smith’s shot, if it actually happened as described. If the tale stated that it was done with a tang-sighted Sharps .52 caliber rifle, I’d say “well, yeah, probably” due to Smith’s shot, which has been duplicated in the modern era with similar arms.

I’d have to see somebody duplicate it with a scoped Civil War “benchrest” muzzle-loader to believe it actually happened as described.

cheers

eon

Yup, I agree.

Width, or diameter, really doesn’t serve to indicate magnification. Scopes with magnifications up to 20x, 25x and even 30x were made on straight tubes, typically 3/4″ or 7/8″, sometimes also 1/2″, and usually full-length, before and during the time of the US Civil War. Makers included L M Amidon in Vermont, Morgan James of Utica NY, James’ former associate George H Ferris (or Ferriss) also of Utica NY, William Malcolm in Syracuse NY and others.

Malcolm and others made scopes up to 20x (at least) before and during the Civil War. I have seen a 20x Malcolm made in 1858 on a .50 caliber Billinghurst underhammer target rifle with Civil War provenance. The owner was an elderly gentleman in Mississippi who shot it at our club from time to time(early 1990s). It was one of the simplest yet most elegant rifles I have ever had the pleasure to shoot. Unfortunately, we only had a 300 yard range, and I only fired one shot … right through the ten ring. I don’t recall the powder charge he used, but with a barrel as thick as those, and as heavy as those rifles are (this one weighed over 30 lbs.), I don’t doubt that they could easily handle 150 grains or more of powder, placing them in a league far beyond anything an infantry musket (or a Whitworth or Sharps) would be capable of in range or energy. Remember, these barrels are often 4″ or more in diameter and are capable of withstanding extremely heavy charges. They were the Barrett .50s of their day. Ian, I truly hope you get a chance to handle one of these rifles, because it is hard to appreciate their capabilities unless you get to experience one up close and personal. I’ve lost touch with the owner of that particular rifle, but if I run across someone who has one (or I get lucky and find one for sale), I will direct them to this website.

Didnt someone missed decimal mark? The scope might have 2.5x magnification, but certainly not 25. With the tiny objective lens, you will see about as much light as looking trough the welding shield.

Sweeny’s 1920 book Volume III Firearms in American History describes the rifle thusly; “Its weight is thirty-seven pounds; its calibre about

.68; its rifling has six ratchet grooves; the pitch is

of the gain-twist variety, beginning at the breech with

one turn in 5 feet and ending with one turn in 3 feet… …The barrel is

marked ” Abe Williams, Maker.” On an ornamental

insert in the top of the butt is engraved

” Little George Lainhart.” On the left side of the

stock are two gold hearts, close together. The

stock is of rosewood, the use of which for gun stocks

has always been unusual. The fittings and finish

of this rifle are of an expensive character.”

I read that it was a slug gun but that twist sounds slow for a slug. In the late 70’s or 80’s it was owned by S.P. Stevens of San Antonio. He has passed and I am not sure where the gun is now. I remember reading an article about it in, I believe, Gun Report. A picture of it was on the cover. Little George Lainhart was the name.

Scott Somers

Dallas

Little George Lainhart

Gun Report February 1969 Check ebay

The February 1969 article cites information from Ned Roberts 1940 book “The Muzzleloading Cap Lock Rifle” quoting ” Col Charles Sawyer as discussing the shot made by a Union sniper Capt John Metcalf as using the 68 cal slug gun rifle with a machine rest from a high hill One mile 187 feet. In 1969 the gun had gone through several collections including John DeMerritt, J.C. Harvey, then to Johnie Bassett of Arkansas and then to S.P. Stevens who wrote the article for Gun Report. I have no knowledge of its location following his death.