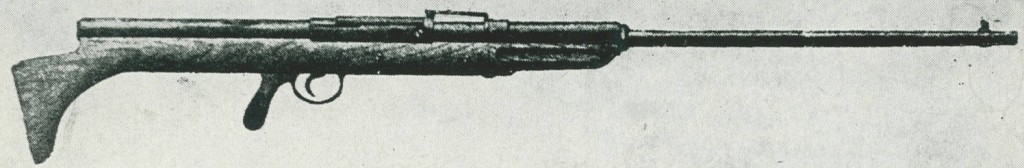

Ferdinand von Mannlicher’s Model 1885 self-loading rifle design as a failure, never seeing anything even resembling mass production. However, it was a failure which in many way set the stage for a huge number of the machine guns that would follow for the next several decades, including the famous Browning 1917/1919/M2 family. In fact, this 1885 semiauto had influence and impact far beyond its level of recognition today. It was a designed doomed to fail despite Mannlicher’s formidable design talents, simply because the cartridge he based it on was the M1877 11mm Austrian black powder round used in the Werndl rifles. Self-loading weapons would not become truly practical in any form until the invention of smokeless powder, which drastically reduced the amount of fouling and residue from each shot. However, Mannlicher was able to at least make a reasonable attempt despite the use of black powder, and he was the first to do so.

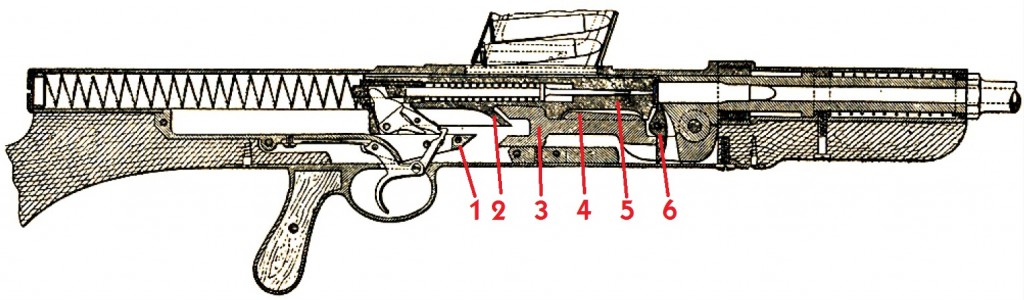

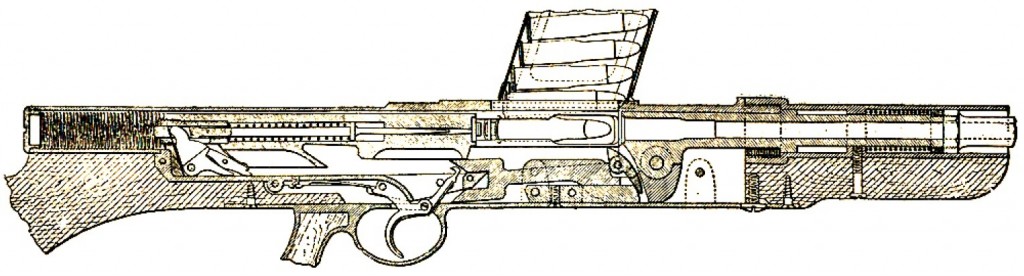

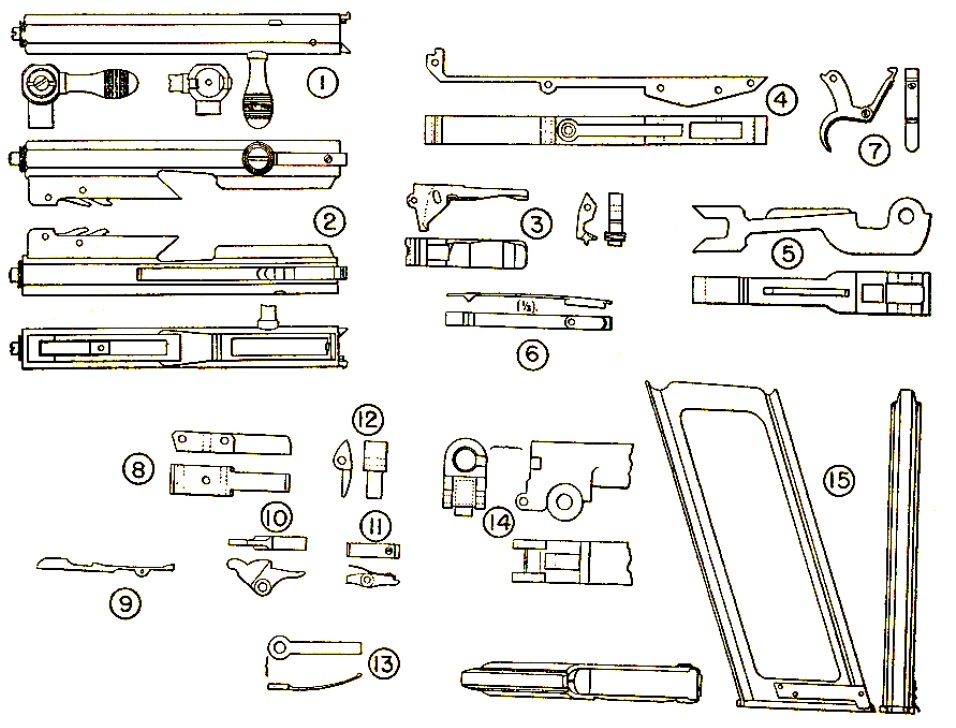

The 1885 design (not to be confused with Mannlicher’s model 1885 straight-pull bolt action rifle) was a recoil mechanism with a separate locking “tong”. As with all recoil-operated designs, the barrel and bolt were locked together at the moment of firing, and remained locked together as they both recoiled rearwards. After a certain amount of travel, in this case about 1.25 inches (32mm) the bolt unlocks and continues rearward which the barrel stops. The locking mechanism in the 1885 Mannlicher is a fork-looking block, labeled #3 in the diagram below. It is pinned to the barrel and able to pivot up and down. When upward, it locks into a cutout in the bottom of the bolt (the bolt is #5 below, and the cutout area is #4). As the bolt and barrel move back, the lower fork of the locking block will eventually hit item #1, an angled projection that forces it downward, unlocking the bolt. Once separated from the barrel, the bolt is able to eject the empty case from the action, and a new cartridge drops down in front of it from the magazine (which is gravity-fed and has no spring). The main recoil spring then pushes the bolt forward, pushing that new cartridge into the chamber. As it moves forward, the hook on the bottom of the bolt (item #2) hits the upper fork of the locking block and forces it into the upward and locked position, thus making the system ready for another shot.

Another element in this action is the use of an accelerator (item #6). It moves back with the barrel until its bottom leg hits a block in the bottom of the receiver. At that point it stops the barrel, and it rotates around its pivot point, with its upper leg pushing on the bolt. What this effectively does it transfer the remaining momentum in the barrel into the bolt, giving it an extra push to help ensure reliable extraction and ejection.

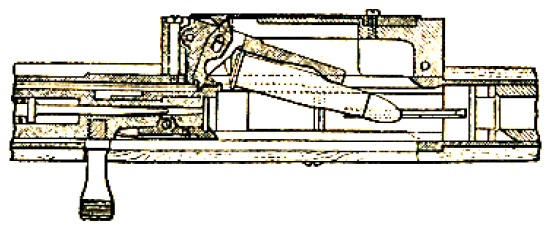

I should also point out that the magazine was offset to the left side of the action, and a loading lever was used to pivot cartridges into the action to feed. The lever was mechanically actuated by a protruding surface on the bolt that would strike it during the ejection cycle:

Today we thing of short recoil as being a common idea/mechanism that has always existed, but Mannlicher was the man who invented it with this rifle. As such, its principles heavily inform the design of most all the other short recoil machine guns that have been made since (fundamentally, the concept of the bolt and barrel traveling a limited distance locked together before some mechanical actuator separates them). The accelerator concept was also a concept used by Browning in his machine guns. And, of course, short recoil because the dominant mechanism for self loading handguns, by way of Browning’s tipping barrel system. Don’t take this as a suggestion that Browning copied Mannlicher’s ideas, because he didn’t – the two men’s guns differ extensively in detail and simply share basic concepts (and Browning added in a huge does of original thought, such as the concept of a pistol slide). However, it is enlightening to understand where the concepts originated.

For the record, Mannlicher did build the 1885 self-loader in both semiauto and fully automatic versions, and he would go on to refine the design as a rifle in 1891 before turning to other operating systems for his later semiautomatic experiments. He never did explore the concept of a light machine gun, which ultimately proved to be a better role for recoil-operated long guns than the shoulder rifle.

Parts identification key:

- Bolt assembly

- Bolt assembly (showing detail of locking lug engagement slots)

- Feeder

- Upper trigger plate

- Locking tongs

- Feeder spring

- Trigger assembly

- Striker head

- Magazine holder

- Striker cocking piece

- Sear

- Ejector

- Trigger spring

- Barrel (details)

- Magazine

It’s also worth noting that in the 1885 model Mannlicher more-or-less inadvertently invented the “straight-line” stock layout, with the stock comb (the recoil-spring tube)aligned with and just above the bore axis. If the actual buttplate had been aligned with the spring tube, he would have had exactly the geometry of such later weapons as the Johnson M1942 LMG.

This would have substantially reduced muzzle climb on full-auto, especially considering the light weight of his designs.

As for the vertical/offset feed, it would have been fairly easily adapted to either a box magazine (as per the Madsen 1910 LMG) or a belt feed (as per the Maxim HMG).

Add a belt feed and a bipod to his LMG, and it could be defined as a forerunner of the MG34.

cheers

eon

Hmm… This also looks as though it came straight out of Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (an old Hayao Miyazaki manga). If Mannlicher’s gun had been tinkered into a LMG, it would have coincided with the original Kjellman, if I’m not mistaken.

Good observation, eon!

Always amazed at the transition period in World Firearm history between gunpowders that varied only in grain size, to “smokeless” powders that are the confusing array we have today. What failed at one period could be a success today.

It looks like it’s the size of a PTRS.

In Smith’s book, he unfortunately does not give a scale on the drawing. But the diagram of the overall rifle shows the hopper-feed magazine with open sides and 11.15 x 58R Werndl rounds in it. Keeping in mind that the “58” is the case length, not OAL including bullet, the drawing, my cm ruler, and Muttonhead (the computer) say OAL of the rifle was 130.5 cm (51.377 inches).

PTRS was 86.61 inches (213.4 cm) long, according to Hogg & Weeks (Military Small Arms of the 20th Century, 1977 ed., p.273). The Mannlicher was 8.6 cm (3.39 in) longer than an M1918 BAR, 20.2 cm (8 in) longer than an M1 Garand, and about 3 cm (1.25 in) shorter than an MG15 with the shoulder stock attached for ground use.

Overall, not bad for a first attempt.

cheers

eon

This looks like exceptionally weird design, but one has to keep in mind year of origin. It must have been a pioneering work for its time which paved the way for much more advanced M1905, shown on FW some time earlier.

Weird, yes, but as you said, Denny, a truly inventive design, considering he likely came up with the concept completely on his own, with no previous designs to borrow ideas from or to illustrate problems that would crop up with use. Even if he could have gotten it to function with some degree of reliability, would there have been a place for it in the tactical paradigm of the mid-late 19th century? Would it have changed the face of warfare, or would it have remained a curiosity? Considering that it came out on the cusp of the smokeless age, the design wasn’t really too far ahead of its time in a mechanical sense, but I wonder how a functional LMG or automatic rifle would have been received by the ordnance department pencil pushers at the time. As for me, I would have them mounted all around the gondola of my steam-powered dirigible as I set off with my minions to conquer the world.

Watch out! For I have a battery of 7.7cm anti-balloon cannons from Prussia and crews to man the guns! And don’t get me started on how many gasoline-powered two-seater scout-planes I may send at that blimp!

I see that you’ve never encountered my minions. If they miss during training, they become the targets for the next class. It’s a great motivator. Those scout planes would be like clay pigeons and the gun crews on the ground would be sniper bait. BTW, I forgot to mention that it is an “armored” dirigible. A megalomaniac intent on world conquest can’t afford to cut corners! (I did stiff Count von Zeppelin on the bill, though. I caught him padding the contract. The gold bathroom fixtures in my private cabin were only 18k instead of 24k. No self-respecting despot would stand for that kind of treachery. Herr Mannlicher was much more accommodating. He gave me the guns if I would promise to make him Emperor of Eurasia. Great guy, old Ferdie.)

I see your minions have never encountered my minions. My pilots wouldn’t let themselves be treated as target practice while flying (I personally shot down those who slacked off). I customized my flak batteries with armor protection as well so the gunners can’t be sniped. Don’t fly near flak towers, or you will till soil! And this week the first squadrons of Avia B.534’s and Fokker D.XXI’s arrived to replace the aging RAF Se.5’s. I also sent a few Caproni Ca. 132’s after your dirigible’s base while you were out!

I’m wonder about reliability of gravity-feed magazine. Austrian Salvator-Dormus 1893 machine gun used gravity-feed magazine, however it used 8x50R Mannlicher round and was machine-gun on mount not shoulder fire-arm. http://www.hungariae.com/Skoda.htm states that “Its weekest point was the gravity fed open sided magazine which caused an occasional malfunction.” so I suspect that Mannlicher 1885 might be prone to malfunctions due to dirt entering magazine.

Gravity feed was the standard of the day on manually-powered machine guns like the Gatling, Gardner, Nordenfeldt, and etc. So it’s probably not a surprise that Mannlicher used it on his auto-weapon design.

And NB; the only spring-fed box magazine around at the time was James Paris Lee’s, and it was patented. The German Commission Rifle with its fixed box magazine was three years down the road at this juncture, and IIRC Mannlicher had a hand in that, mainly designing the bolt system.

The Austrian Schulhof of 1889 had a very weird gravity-feed magazine in the stock, with three columns of cartridges that dropped into a semi-tubular feedway where they were taken forward by a feeding system much like the Winchester-Hotchkiss tube magazine. I can only assume that holding the rifle absolutely upright while firing was highly advisable.

The highest-firepower magazine system of the day was that of the American Evans lever-action repeating rifle. Externally it looked like a Spencer minus the big external hammer (it had a spring-driven internal striker like a Martini-Henry single shot).

Its magazine was an Archimedean-screw helical gadget that held up to 30 rounds of (usually) .44 Evans ammunition (roughly equivalent to .44 S&W American revolver cases, but with ballistics similar to .44-40 WCF). There were no springs in the magazine; it was powered entirely by the lever action. (Working it must have required some oomph.)

The modern-day Calico weapons, in 9mm and etc., use a variant of the same magazine concept. However, it is spring-powered by a system similar to the drum magazines of the Thompson and PPSh-41 SMGs of two generations past.

No, there really isn’t very much new under the sun.

cheers

eon

Thanks Ian for this very important historical post. However, the piece named “Accelerator” seems rather “Decelerator” which slowing and giving more power to the item to be exerted. It looks simply a powerfull extractor like break open, or falling block or, rolling block firearms. Parts list also does not contain another element excepting this little lever named”Ejector”. The rifle should be though to eject the empty case,

first by powerfull push of that lever, nearly as a primary extracting, and then, by force of remaining gas within the bore. Any angled or protecting part or surface then to strike and eject the case in motion.

Correction; Parts list and sectional drawings show the presence of, at least, one extractor.

Fascinating find. Would be interesting to timeline these early developments.

That’s pretty radical for the era, cool.

Not to detract from Mannlicher in the least, but wasn’t Maxim’s first patent machine gun (demonstrated in 1883) also a short-recoil weapon? And in the animation that linked from here on FW, that action not only has the famous toggle-crank lock but an additional breech-to-chamber U-shaped lock that is cammed upward into unlocking on the recoil stroke.

So I would propose that the genesis goes like this: Volcanic/Winchester lever-operated toggle lock evolves into Maxim machine gun’s short-recoil-activated toggle lock; the toggle lock is adapted by Borchardt for his C93 and is refined into the Luger; the lifting (or dropping) lock, abandoned by Maxim, is either adapted or independently invented as a parallel development by Mannlicher in this shoulder weapon, and also adapted into pistols via the Mauser C96, Bergman, BAR, Lahti, Walther P38, Beretta etc.

The accelerator device must have existed in engineering lore before Mannlicher, Browning, and Lahti put them into guns, as it seems to work from such a simple geometric principle. Might not some piston steam engines have been equipped with such things?

To Mannlicher’s credit must go his ability to adapt the Maxim action to a self-loading single-shot shoulder weapon, unless he did in fact invent this rifle in ignorance of Maxim’s patents, in which case the credit he deserves is much greater.

I would like to know who developed blowback first: Mannlicher or Browning or someone else? And did the original Austrian patents for the Hotchkiss gas-tube gun predate Browning’s potato-digger?

There were smokeless powders around prior to that, going back to the 1860s in Austria (invented by Captain Schultze) and manufactured into the 1870s (when it was shut down by the Austrian government due to their monopoly on powder production) by which point production had already begun in England along with improved variations of that powder. (the initial English patents date to 1864)

The powder was of the bulk sporting powder type (made from nitrated wood meal), too fast burning for large military cartridges, but useful for shotgun shells and pistol cartridges and thus would have made sense in automatic shotguns or pistol-caliber rifles. (certainly a repeating small-bore light rifle akin to small frame winchester repeaters of the period)

http://www.gunshoplosangeles.com/Pyrotechnic/Pyrotechnic_Books/Tenney_L._Davis_Chemistry_of_Powder_and_Explosives_Ocr.pdf see page 287

Hmm, you know, with Major Fosbery’s rifled choke patent, combined with the smokeless shotgun powders in production by the 1870s/1880s in Europe (in Austria initially, but also in England, where it remained when the Austrian plant was shut down due to government monopoly on powder manufacture). The powder was too fast for practical use in rifles, but worked well in smoothbore weapons due to the lower initial pressure spike (no rifling to engage) and combining that with a rifled choke would seem ideal for an early self-loading rifle like Mannlicher’s 1885 short-recoil design. (using a light, pistol caliber cartridge also should’ve been low pressure enough for such powders, but marginal in the military role similar to the trade-offs of the 1866 Winchester in military use, but also with the smokeless powder advantage)

This would be the powder invented by Prussian artillery captain Johann F. E. Schultze, and improved in 1882 at the Explosives Company at Stowmarket, England. (it was originally just nitrated wood pulp/powder mechanically bound with potassium/barium nitrates, but this added a partial gelatinization step, turning it into a powder of similar quality to ‘bulk sporting’ type shotgun powders used into the 1930s, particularly by Dupont very roughly equivalent to some modern shotgun powders or Trailboss … a bulky, fast-burning, low pressure-optimized propellant)

It would not be particularly well suited to high velocity small-bore rounds, though … more like some modern smokeless loads for old low pressure black powder cartridges. (still a major innovation for the time due to the lack of thick smoke and potential for self-loading weapons if still only modestly more potent than pistol-caliber lever-actions of the period) OTOH, they could be designed to easily fire shot as well as slugs, a major possible tactical advantage (especially in colonial use … prior to the Hague Convention niggles)

Two phos this rifle https://mpopenker.livejournal.com/2356347.html#comments