It is often said that the 1907 Mondragon was the first self-loading rifle formally adopted by a military, but it turns out this is not quite accurate. In fact, the 1896 Madsen-Rasmussen rifle was produced and adopted more than 10 years earlier (although only in small numbers).

M1888 Forsøgsrekylgevær

Development of the weapon that would eventually become the very successful 1902 Madsen light machine gun began many years earlier, in 1883. Two Danes, Madsen and Rasmussen, began working on a recoil-operated self loading rifle design that year, with Madsen developing the idea and Rasmussen fabricating the actual pieces. The project was made difficult by the black powder cartridges available at that time (black powder fouled intricate mechanics quickly, and also created a relatively poor recoil impulse compared to later smokeless powders), but by 1887 they had a workable gun completed. This rifle, designated the M1888 Forsøgsrekylgevær, was entered into Danish military testing, and went so far as to have 50 rifles field-tested by a battalion of troops. The conclusion was that the design wasn’t good enough for infantry use (although it was considered for fortress use, which would presumably be a cleaner environment that being in the hands of field infantry units), and the Krag-Jørgensen was selected instead for general issue.

Note the very small bayonet, typical of recoil-operated rifles in which too heavy a bayonet will cause the rifle to malfunction by increasing the weight of the reciprocating barrel assembly (the M1941 Johnson rifle was also recoil operated and used a similar style bayonet). As testing progressed, stacking swivels were added to the guns.

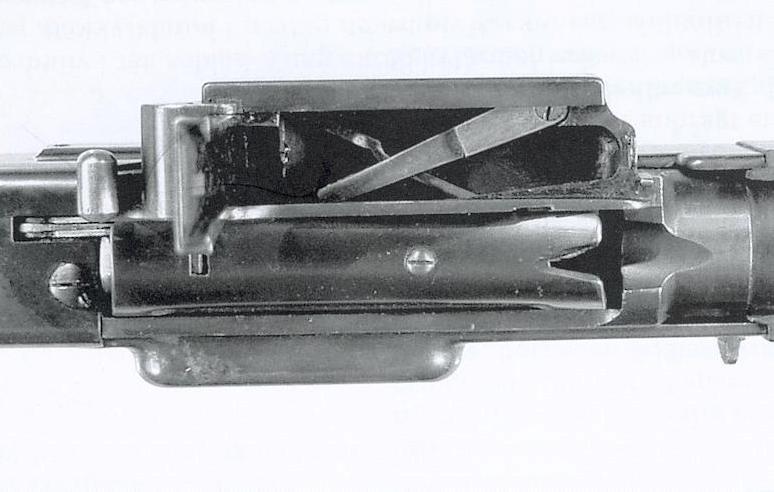

This first 1888 model of the rifle was conceptually identical to the final light machine gun evolution, so watching our video on how the Madsen LMG functions will be very helpful in understanding the mechanics of this earlier version. The side of the receiver could be opened for access to the operating parts, and it present a pretty daunting sight:

I haven’t been able to examine one of these rifles in person, so I can’t describe all the details, but when one compares the parts to the Madsen LMG, some things become apparent. The main component has a cartridge-shaped hole in it just like the LMG, and the magazine is located in the same position (top left side). Not the connecting piece at the tail of that large piece; it is connected to the lever extending back from the trigger guard. This takes the place of the charging handle – pulling that lever down and forward acts to pull the whole breech assembly rearward, manually cycling the action. Empty cases are ejected down and backwards – where the LMG re-deflects the slightly forward, the 1888 rifle simply has a chute to allow the cases to exit the receiver backwards.

The magazine on the 1888 Madsen-Rasmussen was actually gravity fed, and rather similar to the Bruce feed stick for the Gatling Gun. A cartridge holder (effectively a non-removable stripper clip) stood at the back of the magazine, and would hold cartridges by their rims (this rifle was chambered for the Danish 8x58R round) and allow them to slide down into the action as necessary. When not in use, the holder could be folded forward to act as a magazine cover and keep dirt from entering the action.

Without seeing more detail, I unfortunately don’t see what part(s) served the function of the cartridge ramming finger from the LMG. A brief video clip of the action being manually cycled with the side cover open would be very informative, but we don’t have a clip like that.

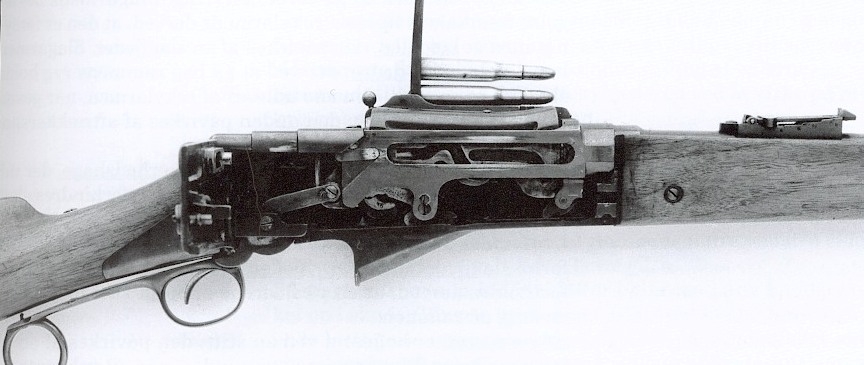

M1896 Flaadens Rekylgevær

After losing out in the 1888 trials, Madsen and Rasmussen continued to refine their rifle. They reduced the overall length and weight, and replaced the feeding clip with a more modern enclosed magazine (although as far as we can tell is was still gravity fed, without a spring or follower). The mechanism was refined for more reliable functioning, including changing it to more positively control the position of cartridges as they were fed. The Martini-like rear charging lever was replaced with a more modern rotary handle on the right side of the receiver. Still, the basic mechanism remained the same.

This 1896 Madsen-Rasmussen rifle was again considered by the Danish Military, and deemed reliable enough to limited use. A total of 60 rifles were purchased and issued by the Danish Navy for use in defending coastal fortifications. They were never used in anger, but remained in the Danish inventory until 1932.

With the success of the 1896 model’s sale to the Danish Navy, it was time to expand sales internationally. A company was formed in 1898, which would soon become known as the Danish Recoil Rifle Syndicate, and Madsen and Rasmussen sold their patent rights to it in exchange for royalties on future production. By 1899 the company manager was Lieutenant Jens Schouboe, and it is his name found on the subsequent Madsen LMG patents. For this reason, the Madsen is sometimes referred to as the Schouboe rifle.

In 1903, the US military tested one of the 1896 model rifles (which they identified as a Schouboe) chambered for the new US .30-03 cartridge. This appears to have proved too powerful for the rifle as it was built at the time, although further tests were conducted on the gun in 1905, 1906, 1909, and 1911. The final 1911 report on the rifle listed a number of faults, including:

- The magazine could hold but five cartridges (this seems odd given the obviously larger magazine on the Danish rifles – perhaps by 1911 this had been replaced by an internal magazine design?)

- The safety features were unsatisfactory

- Rate of fire, 45 round per minute, was insufficient

- It was not accurate, due to the recoiling barrel

- Tools were needed for dismounting and reassembling

- There were no automatic indicator showing the number of cartridges in the magazine

- There was no device to show whether or not the rifle was loaded

- The arm lacked strenght and durability the report concluded: “It is inferior to our service rifle in accuracy, serviceability, and in rapidity, the competition had become very much keener and each invention showed the results of accumulated experience.”

I am looking for the full text of any of the testing reports, but have not yet found them. It appears that the US testing board saw better things being developed (they were quite fond of the Bang design, which was in its first tests in 1911) and lost interest in trying to perfect the Madsen rifle.

Regarding “M1896 Flaadens Reculgevaer” I think someone might have misspelled it :-), I’m pretty sure it’s called “M1896 Flaadens rekylgevær” (source, im Danish :-))

My Danish is not perfect, but I believe Rasmus has it spelled correctly. It is surprising that a semiautomatic rifle was developed this early.

Here’s a video link https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=1i59rTpXfj4

The reason the American trial report of 1903 does not match up with the gun is because the Schouboe rifle tested by the US Army was not the Madsen-Rasmussen. It was actually a totally different design (and much simpler) that appeared in about 1902. Typically this was known under the name “Rexer” because at that time Schouboe’s designs (including the Madsen MG) were handled by the Rexer Arms Company in Britain. The partnership between Rexer and Schouboe ultimately did not end amicably and thereafter the Madsen family of guns were produced by the Dansk Rekylriffel Syndikat in Denmark.

The Rexer/Schouboe rifle was trialed in several countries but was not adopted by any. By 1910 it had been abandoned entirely.