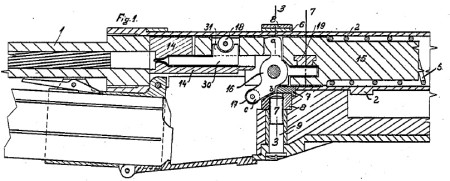

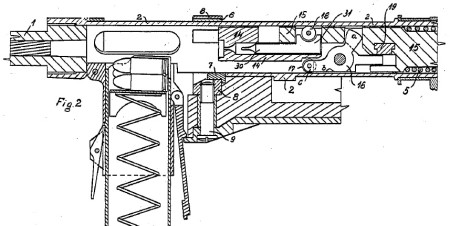

None of Pál D. Király’s guns achieved monumental fame, but he had a long and successful career as a weapons design engineer and became one of those few gun designers who developed a novel operating system to the degree that his name has become directly associated with it. The idea he came up with was the lever-delayed blowback system, in which a two-part bolt and eccentric lever are used. The initial rearward movement of the bolt (while still under fairly high chamber pressure) is done with the lever pushing against the rear half of the bolt, forcing it to move a certain distance before the front half is free to travel. This prevents the breech from opening before pressure has dropped to a safe level. This system was used in a number of submachine guns including the Hungarian Danuvia 39M and 43M, the Italian FNA-B43, the San Cristobal carbine, the French AA-52 machine gun, and most notably the French FAMAS rifle.

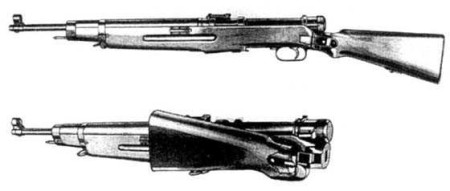

Early in Király’s career he worked as an engineer for SIG in Switzerland, and was involved with the MKMS family of submachine guns, which operated in a fairly similar manner and look very much like Király’s 39M design. The 39M was developed in 1937, and formally adopted by the Hungarian Army in 1939 (hence its designation). It used, of course, Király’s lever-delayed blowback system, and featured a folding magazine well for transport, a 40-round magazine, and three-position fire selector.

The Danuvia 39M (named for the factory where it was manufactured) was not really an outstanding gun in any particular way, but it was a solid, reliable, and well-liked weapons for Hungary during the second world war. The complexity of the lever-delayed system over a typical blowback bolt was justified by the chambering of 9x25mm Mauser Export in the 39M, which was significantly more potent of a cartridge than the other subguns of the day. It fired a 126gr bullet at just under 1500fps, giving it a muzzle energy more than 50% greater than the 9mm Parabellum.

About 8000 of the 39M submachine guns were made for the military, and they were well liked. Reports are that they worked very well even in the cold and mud of the Russian front, and the only complaint was ammunition availability (as they were the only weapons around using 9×25 Mauser ammo).

The magazine was a double-stack, double-feed design, and thus could be loaded effectively without a special tool. When not in use, the magazine and magazine well could pivot forward to be housed inside the stock, with a sliding metal plate to cover the opening and keep the internals free of dirt.

The safety on the 39M was a rotating lever at the rear end of the receiver tube, with positions for safe (Z = Zárva, or “closed”), semiauto (E = Egyenkén, or “one by one”), and full auto (S = Sorozat, or “in-a-row”). Disassembly in the field is very simple – press in the takedown button (see photo below) and rotate the receiver endcap 90 degrees. This allows the endcap to come off, after which the recoil spring and bolt will slide out the back of the receiver.

While the 39M was a popular and dependable weapon, it was too large for easy use by specialty troops like armored vehicle crewmen. An experimental folding stocked version was designed with a hinge in the wooden stock, but this proved unsuccessful (a total of 276 were delivered to the Army in 1940). Instead, an underfolding metal stock was designed, and this version was adopted in 1943 as the (predictably) 43M. The 43M had a few other changes (including a different magazine design not compatible with the 39M), and is worthy of its own article.

Technical Specs

Mechanism: Király lever-delayed blowback

Caliber: 9x25mm Export Mauser

Bullet weight: 125gr

Muzzle velocity: 1493fps (455 m/s)

Cyclic rate: 750 rpm

Magazine capacity: 40 rounds

Overall length: 41.2in (1046mm)

Barrel length: 19.7in (500mm)

Weight, unloaded: 8.2lb (3.7kg)

Weight, loaded: 9.1lb (4.15kg)

Sights: Ramp and post, graduated from 50 to 600 meters

Comparison to the SIG MKMS Family

The 39M bears a great deal of resemblance to the SIG MKMS family of submachine guns, but there are a couple ways to tell them apart. Specifically, the muzzle, stock finger grooves, rear sight placement, front barrel band (or lack thereof), and rotary safety at the rear of the receiver tube:

Additional Photos

This set of photos was posted to Warrelics.eu, of a 39M purchased by a collector in Europe (missing the front band and magazine):

[nggallery id=182]

Patents

US Patent 2,348,790 (P. de Kiraly et al, “Breech Mechanism for Automatic Firearms”, May 16, 1944)

Very interesting operating mechanism. Thanks.

Whew….a 9mm sub-machinegun not far short of a full-sized FN FAL battle rifle in terms of length and weight. On the other hand, the added weight must have made for a very steady firing platform and good recoil attenuation. That wooden stock appears to be really substantial, to say the least.

Will you be trying for a future post on the 43M version as well as the interim wooden folding stock model?

Here in Hungary the general understanding is that the reason for the rather rifle-like form factor of the Király SMG-s was a way to make an SMG armed soldier more difficult to spot against his rifle armed peers, thereby lessening the chance of being directly targeted. I remember seeing some documentation attesting to this, but I don’t recall what it was specifically, so this might not be more than a rumor.

That’s really interesting from the standpoint of military battlefield tactics, Tamas. I haven’t been able to find any hard documentation on this subject either, but perhaps someone else more knowledgeable will be able to confirm or deny it.

Interesting idea, but highly theoretical. It’s relatively rare to see an enemy weapon well enough to ID it by sight at combat ranges. Your enemy is not suicidal; like you, he avoids showing himself until he must.

It’s true that automatic weapons positions get targeted first, tactically, but we’re talking about base-of-fire, sustained-fire weapons like LMGs. They’re real casualty-producers and option-limiters so you want the enemy’s MGs off the chessboard, stat. But you usually target them by knowing the muzzle flash and sound of enemy crew-serves. (If you start the war ignorant of this, you learn fast, and/or die).

Current practice (doctrinal and practical) is to target those weapons with both direct and indirect fire. Direct may get their heads down, but it’s indirect fire that usually pays off. It can be support fire (like artillery on call) or organic indirect fire (your own mortars). As a rule of thumb, if I’m taking effective MG fire from you, you’re in range of my 60mm mortar. I don’t know that WWII era armies used mortars as patrol weapons much (I know Merrill’s Marauders humped them through Burma).

You can also deal with an LMG by pinning it down with fire and flanking the position, IF there is not a supporting position on the flank AND the flankers are lucky.

Now, in 1939 a force might have been correct in assuming that any soldier carrying a handheld weapon firing short bursts was an officer or NCO with a SMG, and therefore a prime target to be sniped. You probably wouldn’t drop mortar shells on him unless you’d run out of higher priority targets like belt-feds.

Also, an army whose combat experience was stale (could that really be said of the Hungarians, 20 years after the Habsburg Empire’s sanguinary mountain fights with the Italians?) might THINK, mistakenly, that they would be subject to someone seeing and sniping their subgun-armed guys. But it seems to me that Hungarian senior officers by 1939 would mostly have been junior officers in that mountain meatgrinder. They’d have no illusions about combat.

Anyway, it’s a very interesting idea and I’d love to see the source if you can find it.

I can’t speak to the idea with the 39M, but the Soviets definitely had that in mind with their WWII flamethrowers made up to look like rifles. ‘Course, the flamethrower guy makes a much more appealing target than someone with an SMG, I would assume.

This site is really a tressure. Thanks Ian.

However, a rough calculation for breechbolt weight

with a safe value of 4 meters per second which

translates only a 2mm backward movement during the

highest pressure within the chamber, gives 900 grams

for a bullet weight of 8 grams and initial speed of

455 metres per second. This is very convenient for

straight blow back operation to use in a firearm of

submachinegun size. Therefore, the lever used on the

Denuvia 39M should be for the purpose of easy and

effective striker cocking rather than blowback delay.

In fact, related patent describtions also reads on

this manner.

According to my sources, the bolt on the 39M weighs only 500 grams.

This is important to know. Therefor, the ratio of bolt mass combined with rifle’s is about 1/7; many modern 5.56 rifles will be about there albeit with lesser final weight. (Some old SMGs vere really heavy.) So it seems that delayed bolt has its justification vis a vis to what ‘strongarm’ says. I like critical thinking of readers in addition of splendid knowledge resource the FW is.

A Delay Lever should be in close contact with the

breechbolt at its front of outer surface of rotation

axis for using the momentum of faster recoiling bolt

carrier to get friction to retard the breechbolt

backward travel and neither the photos nor the patent

text containing such a detail. However, Kiraly was

the inventor of “Lever Delay” operation and it should

be present at the gun itself.

SIG MKMS, though similar at outside, has a different

delay mechanism that may be described like Petersen’s

way used on Remington M 51 pistols in which, slide or

bolt carrier with breechbolt recoiling together for a short and secure distance, breechbolt stops as to

strike an abutment and carrier continues with gained

momentum and unlocks the bolt from abutment. This

operation later changed to simple blowback type for

economical reasons but shows the feasibility of using

blowback action for submachinegun sized firearms using

even most powerfull pistol cartridges.

Sorry, what?

The Király system doesn’t rely on friction, it relies on leverage and inertia.

You’re correct on the MKMS.

Yeah, close relation, true. But than you have coordination of all pieces including receiver with their tolerances. Did I forget something… oh yes: the headspace. Not an easy chore to put it all together. That Kiraly was smart guy, to be sure.

Longer arm of delay lever pushes the carrier block

giving a faster recoil speed and its arched outor

surface at front, being as contact with breechbolt,

delays the backward travel of same as long as the

shorter arm of lever staying within the receiver

recess. Camming degree of arched face from bottom

to top, gives the requıred delay level. Without the

presence of backward thrust of fired case, there

will be no exertion over the arched face and the

breechbolt will freely be drawn rearward by hand for

unloading, loading and check purposes.

Again, what?

The front surface of the lever is not in contact with anything – the rear of arm “a” is in contact with the rear part of the bolt, the rear of lever “b” is in contact with the receiver, and the unlabeled pin in the middle connects the lever to the front part of the bolt.

Your describtion is in limit of drawings and text

of this post and related patent which was the cause

my fırst post. Kiraly is the inventor of lever delay

mechanism, but related document should not be the

sole source of this innovation. Kiraly’s operation

may be confused and leverage facility is used as a

remedy to get the necessary force to continue the

rotating motion of receiver connected lever without

exhausting the remaining gas pressure and gained

momentum to cycle the action. I am not sure this

discussion is useful enough for other readers and

put an end without waiting your third “What”.

Don’t worry, I understand now that you are simply describing a different variant of lever delay.

There seems to be a little bit of confusion creeping in as to the purpose of the lever.

“Lever delay” is probably better described as

“Lever accelerator”

The breech bolt is in two parts, with the lever separating them.

The purpose of the lever is for one end to bear on something fixed to the main mass of the gun, and the other end of the lever to bear on the rear section of the breech bolt.

when the cartridge fires and pushes back on the bolt

the lever rotates, forcing the rear part of the bolt to accelerate at a faster rate than the front part.

because of the leaverage the effect is to make the rear section of the bolt appear to be several times heavier than it actually is

the cartridge case is therefore acting against the equivalent of a much heavier breech bolt, and this slows its initial movement (if all goes as intended) until the bullet has left the bore, and chamber pressure has dropped below that necessary to bulge or burst the case, before the case head web has left the support provided by the chamber.

with a simple blowback, the bolt and the bullet both begin to move simoultanaeously, but the bolt is designed to be heavy enough to move less than the distance to remove the case walls from the support of the chamber.

by putting an accelerator in, you can get the resistance of a heavy bolt by accelerating part of it.

sometime after the bullet has left the barrel, the pin or abutment which connects the two parts of the bolt comes into contact and the front end of the bolt gets jerked back, hopefully bringing the empty cartridge case allong with it and the now combined velocity and momentum are hopefully enough to complete the cycling of the action.

note that the recoil spring does not play a particularly significant role in the delay, its purpose is to slow the parts in the later part of recoil, and to store up the energy from them, then to release that energy to complete the cycle.

The same principal of accelerating a mass is used in the “roller delayed” blowbacks, except they allow the complex geometry of the accelerator lever to be replaced by one or more plain cylindrical rollers, acting against inclined surfaces – which if designed carefully, should be much simpler and cheaper to manufacture.

Friction does play a small role in all self loading actions, but, it cannot be relied upon, as it varies so much between a clean and well oiled (or even greased) gun, and a dirty, dry, fouled or hot or even frozen or rusty action.

The relative masses of the bolt and the bullet are much more reliable factors to design the gun around

Here’s a link to the US patent for de Kiraly’s post war “San Cristobal” .30 carbine

http://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/originalDocument?CC=US&NR=2741951A&KC=A&FT=D&ND=3&date=19560417&DB=EPODOC&locale=en_EP

Thanks for AMX and Keith for clearing the subject.

Regarding to the effect of return spring, and as

Keith pointed out, at instant of time interval of

a few thousanth of a second in which the highest

chamber pressure occured causing a few milimeters

of backward travel, the unfixed propping parts tend

to keep their locations through inertia, and the

coils of return spring join together at front section

leaving little or no compression at the rear support

as giving an additional load roughly equal to its

mass to the recoiling parts. Therefore, the effect of

return spring for retarding the backward travel of

bolt at instant of the time which best needed is

nearly none. Nameing that spring as “Return Spring”

would be better suited for its mission than “Recoil

Spring”.

For benefit of those who are interested in lever delayed blowback mechanism as applied on current firearms, here is a page including patent documentation:

http://www.czechweapons.com/en/about-us/

It is in essence further development of Kiraly’s concept.

It does look like the magazine well cover pivots about a pin oraxle, rather than slides, from the patent drawings. It also looks like the cover is integral to the mag, not the gun. Is that right?

Yes, it pivots.

No, it is not attached to the magazine.

There’s a sort of sleeve holding the magazine – the cover is attached to that.

In fact, any two piece breechbolt of carrier and breechblock construction should

get some delay at opening the breech end due the momentum of striking mass. Delay

mechanisms, apperarently, increaases that momentum via accelerating the rearward

motion of carrier block by means of leverage application providing magnified

momentum at opposite side according the level of leverage.

Another point of view, this event may be explained via the lack of initial return

spring compression at instant of firing due to the mass of coils tending to join

at forward as leaving little or no compression at the back support through inertia.

Delay mechanisms shorten the time to fill the gap of that lack as increasing the

backward speed of carrier block and turn the mission of return spring to the recoil

spring in faster speed than normal. This also explains the sudden jolt occuring to

the breechblock section.

Hi strongarm

In any blowback gun, the momentum of the bolt and of the bullet are the same;

Think of two people stood on skates, each pushing the other away

if you have two people of approx equal weight, they’ll each end up travelling at about the same speed.

If there is a drastic difference in weights, then the lighter one will end up moving much faster than the heavier one, but their momentum will be the same;

Mass one X Velocity one = Mass two X Velocity two.

the reason for using an accelerator and a two part bolt, is,

by accelerating the back of the bolt, you can get the same support to the part of the bolt holding the case head in the chamber, as you would with a much heavier bolt which didn’t have an accelerator.

You haven’t got more momentum by using the accelerator – momentum is the same, you just balance what you’ve saved in bolt weight, by accelerating it to a higher velocity

Thanks Keith,

“Force” had falsely been used as “momentum” somewhere

in my statement.

What about your opinion for “Turning return spring to

recoil spring by accelerating two piece breechbolt”.

This was offered to the British in 1938 by Mr Dinely of BSA. Dinely went on to develop his own version. The Brits were not interested in either and ended up buying Thompsons.