When Colt decided that it wanted a piece of the Derringer market, it used a tactic we are used to seeing today: it found an existing manufacturer and just bought them outright. This was the National Firearms Company, which was manufacturing a Derringer designed by Daniel Moore in 1861. Moore made the guns himself until 1865 when he sold the rights to National, and they made them until being purchased by Colt in 1870. This design then became the Colt 1st Model (and 2nd Model) Derringer. It used a knife blade type extractor, and was offer in all-metal construction (the 1st model) or with wood or ivory grip panels (the 2nd model). Both of these Moore designed types were made until about 1890, with about 15,000 total being made.

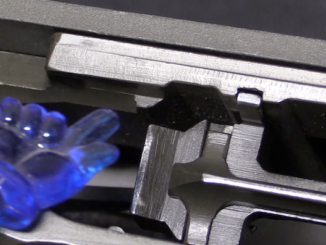

In about 1875, Colt engineer F. Alexander Thuer (who previously designed Colt’s cartridge conversion for percussion revolvers) designed his own Derringer. This used a barrel that open to the side, and a spring extractor. It was more efficient to produce than the Moore design, and it became the Colt 3rd Model Derringer. It was produced until 1912, with about 48,000 total made. Production of a 4th Model actually began in 1959, with periodic production runs. These last guns were in .22 rimfire.

The first three Colt Derringers are all chambered for the common .41 rimfire cartridge, with occasional very limited production in .41 centerfire. The standard barrel length was just 2.5 inches, although many variations exist in small numbers.

The odd shape of the Moore design becomes understandable once you realize that it was intended to be fired from inside a coat pocket. The shooting hand grips it from above rather than behind, and the proper address puts the second finger on the trigger rather than the first finger, which goes around the barrel ahead of the “step”.

The front sight is there mainly for looks, as the hammer blocks any view of it from behind at all times, whether cocked or uncocked.

The rarity of centerfire Moore derringers is due to the fact that those were early models. Originally, the Moore was designed as a percussion cap fired muzzle loader with a completely enclosed cap nipple. When Moore changed the original percussion design to metallic cartridge, he first chambered it for a proprietary .41 caliber cartridge similar to the British .410 revolver round;

https://forum.cartridgecollectors.org/t/f-joyce-410-centerfire-revolver-british/42591

In the end, the Moore derringer was apparently chambered for the .41 Remington rimfire round simply because the Remington Double Derringer and its ammunition were already on the market.

clear ether

eon

“(…)41 Remington rimfire round(…)”

According to https://naboje.org/en/node/4814 one of names used .41 – 100 Derringer, was it actually used back then? In reality it is impossible to pack 100 grains of powder into case, so clearly it was used in order to enhance confusion, but by whom?

The “100” referred to the bullet weight in grains, not the powder charge. The full designation was .41-12-100; .41 caliber, 12 grains FFg black powder, 100-grain bullet. Later loadings increased bullet weight to 130 grains by substituting a solid-based bullet for the original hollow-based type.

It’s like the .38-40 Winchester Center fire. The “.” should be in front of the “40”, not the “38”, because is a true .40 caliber (.401in bore). And it was originally loaded with a 180-grain lead semi-flat-nosed bullet (for safety in the tubular magazine of a Winchester lever-action rifle) in front of 38 grains of black powder. The correct designation would have been .40-38 WCF, but they just didn’t do it that way.

The .44-40 WCF, by comparison, shoots what it advertises. .44 caliber (actual .429in bore), 200-grain LSWC bullet, 40 grains black powder. And yes, out of a 4 3/8″ to 7 1/2″ revolver barrel, it generates higher velocities and more muzzle energy than the .45 Colt’s 255-grain “service load”.

And also yes, the .44 Remington Magnum outdoes them both, even with “medium velocity” 250-grain LFN factory ammunition. It rendered them obsolete except for nostalgia reasons in 1955.

cheers

eon

Isn’t the proper spelling, Deringer, with one “R”?

Or maybe as one of my Georgian (State, not Country) co-workers

called it, the Derllinger.

According to https://thecontentauthority.com/blog/deringer-vs-derringer

When it comes to firearms, the spelling of their names can be just as confusing as their operation. One particular example is the spelling of “deringer” and “derringer.” Which one is correct? The answer is both…Derringer is a variant spelling of the word “Deringer”. The difference in spelling is believed to have arisen due to a misspelling on the part of an early manufacturer of the gun. Despite the difference in spelling, Derringers are essentially the same as Deringers in terms of design and function. They are small, single-shot or double-barreled handguns that were popular in the 19th century for their ease of concealment and reliability.

the 100 is about projectil weight, not the power charge

You should also note that Derringers were often carried in pairs, and as back-up guns, and sometimes in even more than pairs. If my memory of what I read is right, Daniel Sickles was carrying seven of them (several of which misfired) when he shot Philip Barton Keys in 1859. (Somehow Sickles prevailed on a defense of temporary insanity.) How many pockets did a gentleman’s suit have back in those days?

Nice guns and nice video, which I have waited for a long time. – I hope the single shot Remington-Elliot “Mississippi derringer”‘s video also will coming (soon).

The Colt #3 Derringers in .41 centerfire were chambered in .41 LONG Colt.