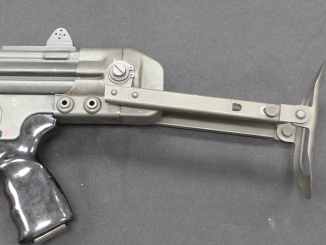

Manufactured from 1899 until 1905, the Charola y Anitua pistols (later becoming just the Charola pistols) were basically scaled down C96 Mauser designs chambered for the 5mm Clement and 7mm Charola cartridges. They were briefly tested by the Spanish military, but not adopted and ultimately only sold on the commercial market. A total of about 8400 were made, probably split about 50/50 between the two calibers. By the end of production they were made with detachable magazines in the hopes of competing with the other guns then available, but with their rather bulky ergonomics and underpowered ammunition they would not survive long.

The information in this video cam form Leonardo Antaris’ excellent book “Astra Pistols & Selected Competitors“.

Since the locking block mounted on the receiver, bolt seperatio from the barrel begins as soon as the recoiling action begins. Therefore this is a delayed action pistol rather than locked breech.

I think this locking system is very similar to the Revelli 1914 machine gun. I agree it is delayed blowback .A very good animation exists on VBBSMYT of the Revelli. Very unusual

in this gun is that the lock engagement is adjustable so that more recoil energy can be

imparted to the bolt.

Do not know the exact connection but it seems the designer of Glisenti 1906 and this pistol being same or very inspired with each other. Fiat Revelli 1914 MG should be a continiation of this design. Years after FN FiveSeven also constructed over this lay out.

A particular Captain Revelli designed both the Glisenti and the M1914 machine gun. The latter was designed as “short-recoil” but functioned more like a delayed-blow-back if you take the harsh extraction phase and short “unlocking time” into account.

“5mm Clement”

It was later used in Clément automatic pistol:

https://unblinkingeye.com/Guns/Clement/clement.html

having more normal (for us) layout of magazine in grip.

Only known ballistic data according to data in above link:

36 gr @ 1030 fps @ 2.716 inch barrel.

Interestingly: The 5mm bullet is said to be unstable in flight, tending to tumble, which might have contributed to its effectiveness for self-defense though perhaps not to its accuracy.

Which lead me to wondering about whatever it was intention of its designers or just coincidence that such rifling profile/bullet give such effect?

Clément later switched to 6,35 mm Browning [.25 Auto] cartridge, but I would want to know if that was effect of considering ballistic of these two cartridge or just caused by rising popularity of second?

I want also to point that in similar time Bergmann produced his No.2 automatic pistol:

https://www.forgottenweapons.com/early-automatic-pistols/bergmann-no-2-1896/

also firing similarly small cartridge, although differing in having tapered case and… lack of extractor groove in original version. Interestingly Bergmann product evolved in similar fashion – offering bigger caliber and detachable magazine.

The (to modern sensibilities) odd cartridges remind me of a question I’ve had: How expensive was ammunition in the early days of metallic cartridges up until say the 1940’s?

The plethora of such anemic cartridges suggest to me that humans were far more fragile, easier to kill or disable back in those days than humans are nowadays.

More like: current medicine had no way of saving you from a puncture wound in the guts, whether caused by projectile or stab, nor did any human have reasonable expectation of surviving a head wound. Plus you would die most painfully of sepsis or peritonitis. The deterrent effect of any firearm, or even a blade or spike, should not be underestimated in these days of high ballistics and modern trauma medicine (and drug-fueled irrational attackers). The anemic cartridges resulted from the fears of manufacturers of opening an unlocked breech — hurt users were bad for sales. Colt itself would not buy a blowback design from Browning until the wide sales and reliability of the FN1900 in 7.65 proved that “larger” blowback was a safe proposition.

Perhaps the intent was not “one-shot-stopping” but emptying the pistol into your assailant. The mugger is certainly no Jet-Li.

“expensive”

Some data from ALFA catalog (Germany, 1911) prices for 1000 examples, prices in Mark:

6,35 mm Browning made by FN: 72

7,65 mm Browning made by FN: 79,20

.380 Auto: 96

.38 Colt Automatic: 118

.45 Colt Automatic: 140

7,63 Mauser: 96

same as above but in strippers (10 rounds/stripper): 104

9 mm Parabellum: 106

And for comparison some pocket automatic pistol from same source for example, again all prices in Mark:

Mauser Mod. 1910 steel parts black, walnut handle 59

Pieper (6,35 mm) 45

Pieper (7,65 mm) 52

Clément (6,35 mm) black burnished rubber grip 53,20

Clément (7,65 mm) black burnished rubber grip 60,80

Clément (7,65 mm) nickeled 63,20

Clément (7,65 mm) with mother of pearl grip 76,80

Clément (7,65 mm) nickeled and with mother of pearl grip 79,20

So 1000 rounds of 7.65 / .32 cost the same as Clement nickeled, pearl handled pistol (DM79.20)?

Whereas a 1000 rounds of a common caliber now (9x19mm) costs about $150 here in the US, and no new 9mm pistol worth a damn costs that little.

So, a quick internet search says that in 1913 one US Dollar was worth 4.20 Marks, and one UK Pound Sterling was worth 20.429 Marks, which fits with my faintly-remembered reading that five Pounds equaled $1 US for many years back then.

Incidentally one of the on-line experts calculated that $100 US in 1900 had the buying power of approximately $2,827 today, so a factor of 28. Certainly you could buy beer for a nickel (and sometimes get accompanying food for free!), a sausage sandwich in a Chicago restaurant cost a dime, and the cheapest revolver in the 1903 Sears catalogue went for $1.50. An S & W hand ejector started at $10.50, the Colt large .38 auto for $18.50, and a Winchester pump shotgun for $17.50.

Don’t know where your 9 x 19 is coming from but I’d say $220 for 1,000 rounds nowadays as the cheapest retail price plus tax, but I don’t know what deals Sportsman’s Guide has been offering lately.

Yes, if you wish to compare to other currency you could use this:

https://www.historicalstatistics.org/Currencyconverter.html

It says that one 1911Mark is equivalent to ~5,43 of 2015$ in terms of amount of consumer goods and services in Sweden and you would need same amount of hours of work in Sweden in 1911 to get 1 Mark and in 2015 to get ~54,26 $. By comparing gold prices 1 Mark in 1911 is equivalent to ~13,15 $ in 2015. [2015 is most recent year available for $]. As you can see coefficient vary greatly depending on method used.

The two pivot pin/screws through the frame are called binding posts, because of the little nub on the shoulder to keep the un slotted end from turning. Similar fasteners are also called Chicago screws (slots on each end) and sex bolts (held closed by compression).

Charolas are hilarious, even more so to shoot.

Predecessors of the Astra 900/903/F clones