We have previously mentioned Fridtjof Brøndby, a Norwegian arms designer who created a number of self-loading rifle designs in the 1930s. Last time we were looking at his model 1933 maskinpistole (submachine gun), and today we have a bunch of photos of his full-size self-loading rifle prototype. We still have very little information on the man – or on the details of just when this rifle was made and what caliber it uses – but we can learn a lot from the photos.

This rifle is in the collection of the UK’s National Firearms Centre (aka Pattern Room), which suggests that it was sent to England for military testing. We don’t know the details of those test (if they were ever completed), but clearly the rifle didn’t do well enough to be developed further, or adopted. Still, the design seems pretty good for the early 1930s, if a bit bulky.

The broad view is that the Brøndby rifle is magazine fed, fires from an open bolt, operates with a long-stroke gas piston, and uses a vertically-traveling block which locks the bolt into the bottom of the receiver.

Disassembly is wonderfully simple – first the lower handguard detaches much like a double-barrel shotgun foreend:

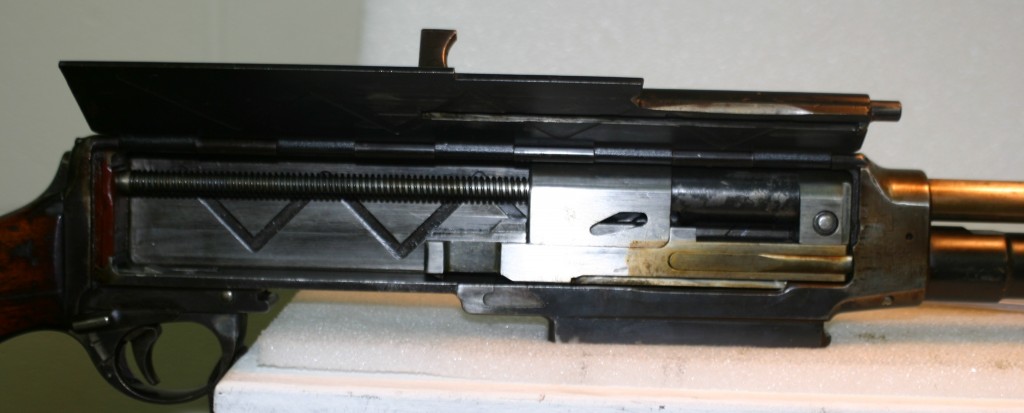

Next, the entire right side of the receiver opens up on a long hinge to reveal the internals:

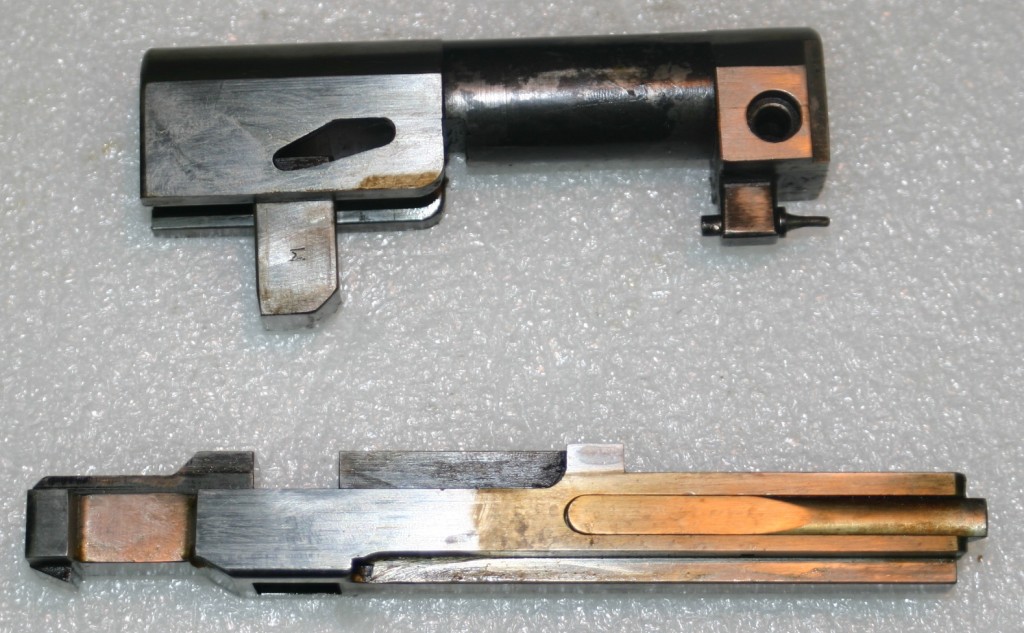

From here, most of the operating mechanism becomes clear. The gas piston atop the barrel is connected to a bolt carrier inside the receiver (the round pin at the front of the carrier is the pin connecting it to the moving piston – remove that pin and the carrier can be removed). A square block somewhat like a C96 Mauser or Bergmann 1910 locking block is carried inside the bolt carrier, and drops down through the bolt to lock into the bottom of the receiver when the bolt is in battery. On the bottom of the receiver just behind the magazine well you can see the locking shoulder this block pushes against – it is a removable piece, allowing it to be hardened independently of the receiver body, and to be interchanged to change the headspace of the rifle.

The rifle fires from an open bolt, as evidenced by the fixed firing pin and lack of any linkage from the trigger up to the bolt. Instead, the very rear of the bolt has a catch which engages the firing mechanism, so that upon pulling the trigger the bolt is driven forward by the mainspring, strips a round from the magazine into the chamber, the locking block drops into place, and the round fires. Gas from the barrel then vents into the piston, which pushes the bolt carrier backwards, which cams the locking block upwards. Once the locking block clears the locking shoulder in the bottom surface of the receiver, the bolt and carrier travel backwards, ejecting the spent case and being caught by the sear at full travel, ready for another shot.

The safety lever near the trigger appears to have three detent settings, so I think it is safe to assume that the rifle could fire either semiauto or fully automatically. Also note the zigzag grooves cut in the receiver walls, very much reminiscent of the cuts on Israeli FAL bolt carriers. We can’t ask Brøndby about them, but they appear to serve the same purpose – giving dirt and carbon residue a place to go without interfering with the rifle’s operation.

Really, the only major issue I see with the design is the lack of a safety mechanism to prevent out-of-battery firing. Since the firing pin is fixed to the bolt carrier and the carrier positively forces the locking block into place, firing out of battery would not be possible. It would be nice to see a redundant system in case the locking block were damaged or inadvertently left out when reassembling the weapon, though.

You can see many more photos of the Brøndby rifle here, and download the complete batch in high resolution as a zip archive:

[nggallery id=190]

That looks like it could have been refined into a decent machine gun…

Here is thinking “out of the box” in practice. Simple and efficient design. One really has to wonder why this did not take the world.

This seems to be the later, simplified version of the Brøndby self-loading rifle, with minimalist furniture. Earlier – or full military – versions had traditional type stocks, complete with bands, bayonet lug and cleaning rod.

Thanks for posting these excellent photos, Ian! This is why I am going to support your efforts by becoming a member!

A nice, ingeniously simple and robust gun that appears to work very well, judging by the photos and description. The reasons for this rifle failing to be adopted into general service may have little or nothing to do with its design, capability and mechanical reliability / functionality, but may instead be related to any one or more of other numerous factors ranging from politics, logistical entrainment and supply / production issues and prior commitment to other weapons systems to plain prejudice against “foreign” designs and that old bugbear, market timing. Perhaps the fact that the Brondby fired from an open bolt reduced pin-point accuracy sufficiently to cause it to be eliminated from consideration at a time when an absolute premium was placed in Great Britain ( and elsewhere ) on ultimate single-shot long-range accuracy, even though it may have actually been sufficiently accurate to easily cope with actual battlefield situations. The 1930’s still constituted a period in time when ultimate marksmanship and accuracy at extreme ranges was touted as a most desirable characteristic for a soldier ( or civilian ) and his / her rifle, regardless of the fact that the realities of modern mobile ground warfare would soon show that real-life battlefield ranges were typically much shorter.

Looks very competitive to a BAR if it was in 30-06- probably better.

Just bad timing.