When we think of “last-ditch” rifles, we normally think of 1945 and the very end of World War Two. For the British, however, the lowest ebb of the war was in 1941 and 42, and it is during that period that the Lee Enfield was at is crudest. British ordnance instituted a number of simplifications to maximize weapons production. In particular:

– Walnut replaced with kiln-dried birch and beech for furniture

– Two-groove barrels replacing five-groove ones

– A vastly simplified 2-position flip sight in place of the original fine micrometer style

– Simplified bolt release, designated the No4 MkI* (which was only produced in the US and Canada)

– Aluminum buttplates

– Much reduced standards of fit and finish, leading to really ugly machine marks and haphazard markings.

Most of these changes would be walked back later in the war as Britain’s footing became more solid, but they make a very interesting period of changes for the collector to study.

It’s amusing to think if the Brits had adopted a double-feed mag for the STEN, by 1944 whole British infantry units might have been STEN only on the Soviet model, and this video never made. I remember finding a US Property marked No 4 in a pawn shop in the 90’s – I was astounded & assumed it was a rare variation – thank God for the interwebs today.

That might have been a way to go for the Home Guard in case of invasion, where there’s no point in conserving men. But I think the Soviets were in a better position to make the all-SMG unit work. Part of that was units protecting tanks, for which range is less important than stopping a team from setting up an anti-tank weapon. Also, a bit more effective range on the Soviet guns. And ultimately, the Red Army was more willing to take the casualties from short-range brawls.

Since the decisive phase of most infantry combat took place within the 200m effective range of 7.62×25mm and “hot-loaded” 9×19mm SMGs (at least for armies other than the Wehrmacht, which had the belt-fed MG 34 or 42 on the squad level to greatly augment their long range firepower), an infantry force with only SMGs as personal weapons was likely to suffer LESS casualties than a force with only bolt-action rifles. The firepower advantage of the SMG was simply that big compared to bolt-action rifles. If we do not convolute the situation by introducing semi-auto rifles, an ideal WW2 infantry squad would have had at least half of its soldiers armed with SMGs, possibly even more.

The Soviet all-SMG squads were perhaps less than optimal in a general sense (although quite good for protecting tanks), but they were much better than squads armed only with bolt-action rifles as personal weapons.

The whole thing boils down to tactics and how you’re conducting your operations. If you’re relying on a lot of dynamic movement and tank-borne infantry, then the SMG solution of any caliber makes really good sense. If your tactics are based on relatively static and slow-moving operations conducted on foot, with your soldiers holding the enemy off at the longest range possible…? Yeah; then you’ve really screwed the pooch by procuring a bunch of SMGs.

As well, say you’ve equipped yourself with the World’s Fastest Tank ™, and saddled yourself with timid time-serving hacks as leaders, who utterly fail to take advantage of that speed in order to conduct hard-hitting fast attacks to dislocate the enemy…? You’ve wasted your money on the tanks.

Making war effectively is all about making sure that your tactics, operational intent, and strategy are in sync with your weapons and logistics. If your soldiers are uncomfortable with initiative and independent operation? Don’t base your tactics on them taking charge and adapting to the situations they find themselves in. They won’t succeed. Same soldiers with stolid, unimaginative leadership? They might do quite well for themselves in the right circumstances.

War-making is more about the culture of the war-makers than it is about the toys they use to play the game.

I absolutely agree with you that weapons choices have to match your tactics or you are inviting major problems. It is just that I don’t really see many tactical situations where bolt-action rifles would be better than SMGs in a WW2 context (or even late WW1 context for the matter). Perhaps defense or delay on an open terrain against an enemy with insufficient indirect fire (artillery & mortars) assets could be one, because it would enable the defenders with their rifles to maximize the range advantage.

In most other cases the range advantage of the bolt-action rifle is not significant enough to counter the close range firepower advantage of the SMG. For example if the enemy has sufficient indirect fires at his disposal, the defender with the bolt-action rifles will be suppressed by indirect fire until it’s too late to gain advantage from the long effective range of the rifles.

Much of it boils down to “How do I intend to fight”. In a situation where you have limited, highly-trained manpower you don’t want to waste, then a preference for the bolt-action rifle would suit your intended tactics and operational planning better than arming that manpower with the SMG and forcing them to close with the enemy up close and personal in order to use that firepower.

Likewise, if you have scads of poorly-trained manpower, whose survival isn’t a consideration? By all means, give them the SMG and plan for them getting within knife-fighting range of the enemy before using it.

The whole of it comes down to this: You must understand what you want to do, what you have to do it with, and what the enemy is going to be bringing to the fight. There are fact sets out there where you’d be better off with a bolt-action rifle as primary arm, and then there are others where that choice is going to get you a lot of casualties and a lost war. It’s all highly dependent on the tradeoffs and compromises, just like weapon design itself.

I think a lot of the problem we’ve see seen with historical choices in this arena stems from the people making the decisions being blind to the realities of it all, and ignorant of the demands of modern war. Not to mention, basic human nature–The Germans plumped down for a state-of-the-art GPMG system that was crew-served, thinking that that would provide them with the winning edge in low-level infantry combat. I think they made a good decision, in that they matched their industrial capability with their manpower, tactics, and operational art. Had they tried for the Allied solution, which was to focus on supporting arms and fires…? Odds are pretty good that they would not have gotten as far as they did before the resource constraints hit them. Likewise, had the Allies not been able to mobilize and engage their industrial superiority as they did historically, their choices in terms of going with a magazine-fed support weapon and a semi-auto individual weapon for most of their firepower would have shown tellingly in the quantity of casualties generated by the Germans.

There’s a hell of a lot more to all of this than most of us appreciate; I would submit that the subject area is much broader than commonly defined. Weapons enable tactics which enable operations that actuate strategies, and then the whole thing circles back in either a vicious or a virtual circle of effect and counter-effect. Absent the Allied choices of putting their best manpower into the finest support equipment, the choices they made for infantry weapons, tactics, and manpower allocations would have resulted in a far different WWII than the one we fought.

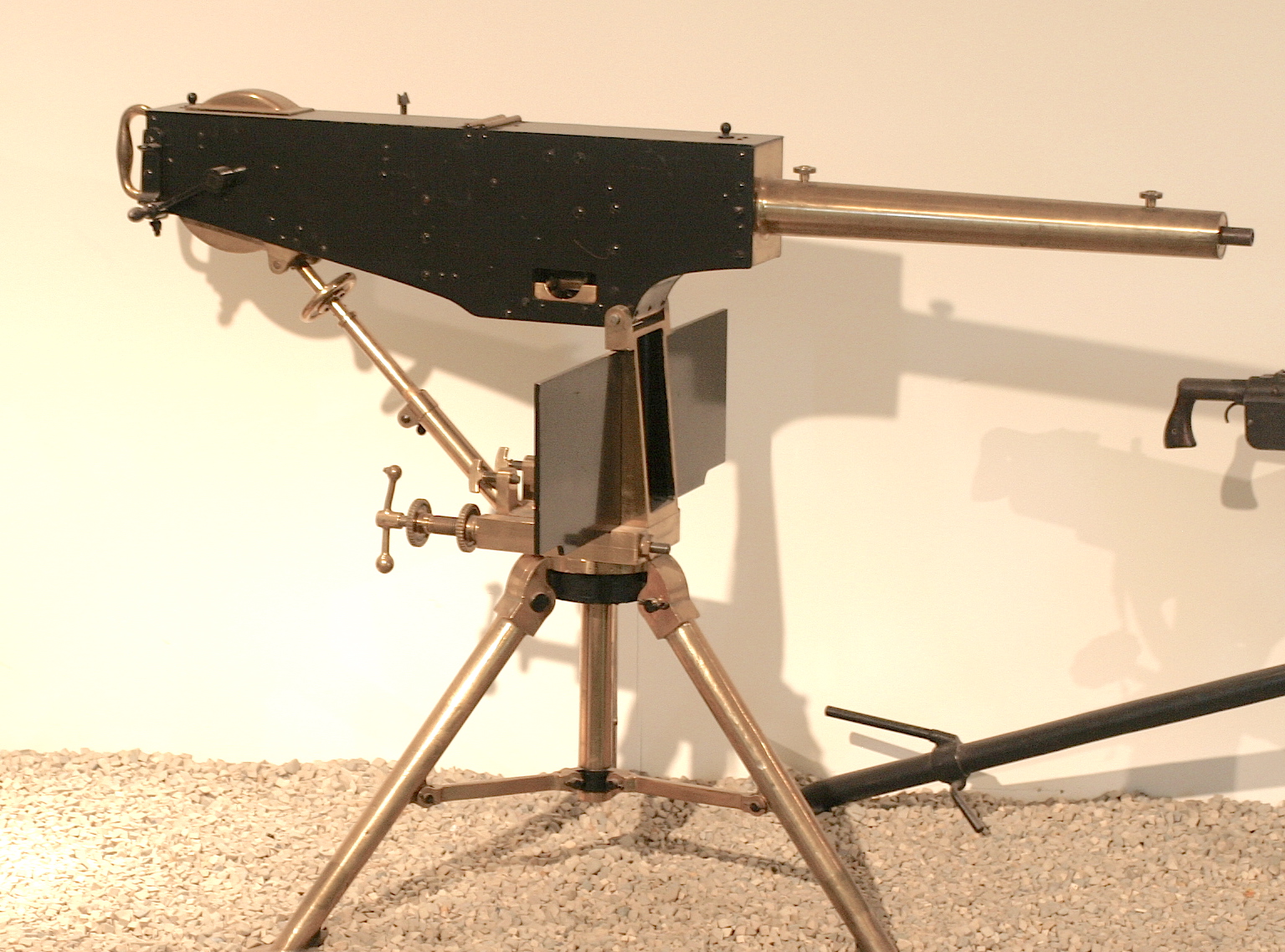

You find this repeated again and again throughout history; the disastrous French experience with what should have been a game-changing weapon, the Mitrailluse, is typical. It foundered on the facts that it was basically just thrown out to the figurative wolves without really bothering to try to understand it or how to best employ it. As an example of the pitfalls of “gadget warfare”, reliant on secret weapons? You’d be hard-pressed to find a better case history to use showing how not to do things.

Same disconnect is demonstrated to this very day–Look at the XM-25. There was what they termed a “de-emphasis” on the 40mm grenade program in favor of the XM-25, because they didn’t want there to be any competition in the budget between those two weapons. As a direct result, we got stuck with the legacy HEDP round that didn’t have much in the way of actual effect for decades. And, again… What was the actual cause? Disconnection between reality on the battlefield and fantasy in the development agencies. The XM-25 was one of those things that the lab-coat types came up with first, sold to the brass, and then never managed to live up to the expectations they created. Odds are, very little of the money sunk into developing that thing will ever return to us in usable form, but I guess we can hope.

You have to establish an honest feedback loop between the battlefield, the labs, and the guys doing manufacture and procurement. Without that information flow, bad things happen. Things like the M73/219 and the M85, along with those other shining exemplars of 1950s US small arms technology, the M14 and M60.

You lock down the feedback, and that’s what you get: Weapons that don’t work, and whose employment doesn’t address the tactical realities. If you’re lucky, you’ll only lose a few lives learning that the hard way. If you’re unlucky, like the French in 1870, you’ll lose the damn war.

1870 is interesting not just because of the mitrailluese; the French inarguably had the superior rifle in the Chassepot, but their tactics made that advantage totally irrelevant. The Germans were using a tactical/operational system that devolved control down to the company level, allowing for much more flexibility and more effective use of what they did have; the French were still using the tactics of the Napoleonic Wars, with the smallest element of maneuver being the battalion. The stunning differences in casualties tell the tale: 53,900 French killed by the Dreyse (70% of their war casualties) versus 25,475 Germans killed by the Chassepot (96% of their war casualties). Or, so saith the accountants and statisticians…

Interesting about the 2-groove rifling. Given the testing results that it was as accurate as 5-groove, why ever switch back?

Was the wear rate the same?

All else being equal

Fewer grooves is supposed to result in slower erosion.

Border barrels were producing some barrels with 3 grooves, for long range target shooters,

To better withstand the higher pressure and heavier bullet loads that long range shooters use.

I have an Alpine commercial M-1 carbine put together in the ’60s that has a 2-groove barrel. I always wondered about it and had never heard of another rifle with only 2 grooves until now.

The bullet of the T65 cartridge had a boat tail.

And such bullets from barrels with two grooves give the worst accuracy.

In all other respects, two is better than four or five.

In addition, with the development of the production of grooves by forging and pressing methods, the number of grooves ceased to affect productivity.

IIRC the butt plate was made of Mazak a zinc alloy not aluminum

Bruce:

That would make sense, as aluminium was an important strategic metal for use in the aircraft industry. No point wasting it on rifle butt plates.

aluminium was an important strategic metal for use in the aircraft industry

And desired to point that subjects of king George VI were asked to provide any aluminium they have at their disposal

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/recycling-win-second-world-war

An official notice appeared in British newspapers on 10 July 1940, the first day of the Battle of Britain. Attributed to Lord Beaverbrook, the press baron turned Minister of Aircraft Production, it was addressed directly ‘To the women of Britain’. The notice called on the reader to give up any aluminium that they could spare. It explained that the metal was needed to produce aircraft for the RAF’s fight against the Luftwaffe. It said: ‘We want it and we want it now. New and old, of every type and description, and all of it … The need is instant. The call is urgent. Our expectations are high.’

“Pots and pans into spitfires”

Was a propaganda drive, aimed at making the war feel “real”, and providing a vehicle for the Karens in Britain to virtue signal their loyalty to the state, and to attack and snitch on their neighbours for not doing enough

The same thing went for donating your wrought iron garden railings and gate for the war effort

It was something that was a very visible display of piety, a bit like ostentatious muzzle wearing and clapping in a Thursday night has been over the past 18 months (or should that be the past two weeks to flatten the curve and save the NHS?)

I’ve not seen hard evidence either way, but I have heard from usually reliable sources that neither the pots and pans, nor garden railings were used for war purposes

The variable composition aluminium and iron was not worth refining for re use.

Interestingly, at the end of ghe war there was a big imbalance in production of steel and aluminium

Steel was scarce, and gh government was trying to keep the expanded aluminium production going

Hence Land Rover and Aston Martin vehicles got aluminium rather than steel skins

‘neither the pots and pans, nor garden railings were used for war purposes’

I’ve heard the same.

After the war the government had a huge surplus of stretchers, stockpiled for carrying mass casualties that never happened.

Many were used to create railings around post-war housing estates.

https://lookup.london/stretcher-railings/

Truly a terrible thing to applaud or show support for people trying to save your life.

“Truly a terrible thing to applaud or show support for people trying to save your life.”

Ah, the Walter mitty dreams of narcissists

And their rage whenever someone refuses to play their drama games

Do you mean zamak ?

By the way, Mazak is a maker of CNC machining equipment.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zamak says

ZAMAK (or Zamac, formerly trademarked as MAZAK…

The full tale of Britain’s readiness for invasion or more effective German blockade/ U-boat and mining warfare-commerce interdiction/ and German aerial bombardment would make a very interesting book.

In addition to the “actually fielded” No. 4 rifles with 2-groove rifling and two-position aperture sights and the Sten Mk.II and Sten Mk.III there were any number of dispersal plans that never came to fruition or saw the light of day.

For example, an interceptor with fixed landing gear (lower maintenance) was planned and tested, but thankfully never flown in harms way. The Faulkner-patented BESAL LMG is much better known, and was developed continuously during the war, but never built let alone issued. At one point, it was thought the spare barrels of the Bren might be used on the BESAL, but in the end, a roughly-machined exterior barrel was planned.

Turning to Chris Macdonald’s copyright-protected material from 2012, we find some interesting stuff:

During WWI, in late 1915/ early 1916 the SMLE Mk.III* eliminated long-range “volley sights,” windage adjustment, the magazine cut-off, and a swivel lug in front of the magazine…

In the mid-1930s trials between various lightened and somewhat simplified rifles led to the decision to place the No. 4 into production “when war were declared.” Two months after the German and Soviet invasion of Poland, the No.4 was adopted — but for some odd reason, people like to exclaim that it was France that adopted the “last bolt-action” rifle with the MAS Mle. 1936.

At Savage in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts and Long Branch in Ontario, there is the No.4 mk.I* From five-groove barrels to two-groove.

By 1942 a more radically simplified bolt-action service rifle was projected, but again, never built. It was a simplified Pattern 14, but made in the UK. It had a 5-shot, charger-fed magazine. It used smaller lengths of wood for the stock furniture, rather resembling French practice with the old Lebel M1886/M93 and the MAS Mle. 1936. Much of the front of the barrel was left exposed. Other prototypes had a steel “skeleton stock” to use even less wood. The all-important-to-Brits bayonet was a simple spike type, again, not too different from the MAS Mle. 1936, but instead of being housed in a tube in the stock, was a socket-type that could be reversed at the muzzle–pointing backwards when not in combat–pointing forwards and remaining fixed like Soviet practice otherwise.

“(…)interceptor with fixed landing gear (lower maintenance) was planned and tested, but thankfully never flown in harms way.(…)”

Never heard about that, only fighter with such feature

http://www.aviastar.org/air/england/miles_m-20.php

its’ max speed was 536 km/h which is not bad compared to Hurricane https://www.aviastar.org/air/england/hawker_hurricane.php?p=2

545 km/h

The Miles Master Fighter (so named because it was based on the Miles Master trainer) also had the advantage that since its fixed, spatted main landing gear did not require space inside the wing, it carried one more 0.303in Browning machine gun in each wing that the Hurricane MK I, and had more room for its ammunition tanks.

Calling it an “interceptor” is correct, as it was the first fighter designed specifically as a fast-climbing bomber interceptor and nothing else. it was also the first fighter in history designed with a one-piece “bubble” canopy giving the pilot unobstructed all-around vision.

Considering its intended operational environment (the Battle of Britain) it probably would have come as a nasty surprise to the Luftwaffe.

cheers

eon

Eon, The British named their trainers with academic names

1) Individuals – Master (degree), Magister (Middle Ages, given to a person in authority or to one having a license from a university to teach philosophy and the liberal arts), Mentor, Tutor, Dominie (from the Latin, dominus “master” as in a schoolmaster), Proctor

2) Schools – Harvard, Yale (both Lend-Lease), Oxford, Cambridge, Henley

Just a little addition: the Miles M.20 fighter was a de facto contemporary of the MiG-1, which was also a dedicated bomber interceptor, designed specifically for high altitude interception. In fact the first flight of the MiG-1 preceded that of the Miles M.20 by a few months, a!though the latter would have probably been ready for production earlier due to being based on the Miles Master trainer.

“(…)Calling it an “interceptor” is correct, as it was the first fighter designed specifically as a fast-climbing bomber interceptor and nothing else.(…)”

Now I am extremely confused, as I always though there must be on-board radar to be interceptor.

That being said it was first specialized bomber buster, as it was predated by malfunction-prone YFM-1 http://www.aviastar.org/air/usa/bell_airacuda.php

The British interception system of the time relied upon the Chain Home ground-based radar system;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chain_Home

Chain Home was the world’s first fully integrated Ground Controlled Interception (GCI) system, and in fact was the pattern for most such systems used by air forces worldwide until the early 1970s.

The purpose of Chain Home was to allow interceptor fighter squadrons to stand ground alert instead of flying standing air patrols, which were hard on planes and aircrews both.

Interestingly, from the first day of the war in Europe until the middle of 1942, the Luftwaffe had no idea that Chain Home even existed. Its radars operated in the 20 to 55 MHz range, while German radars were operating in the 125-400 MHz region.

As such, German radars could not detect the Chain Home system emissions. In one case, in August 1939, the Germans tried to “quietly” fly the Graf Zeppelin airship across the North Sea, loaded with detection gear, to “look for” any British radar systems. They picked up nothing because they were scanning in their own frequencies. They were completely unaware that the airship was tracked from the moment it cleared the Kiel Canal area right on until it returned to the Baltic the same way.

The Luftwaffe did bomb a couple of Chain Home stations. But only because they thought that they were radio transmitters being used to direct RAF fighter groups by voice radio.

During the Battle of Britain in 1940, Luftwaffe bomber crews were consistently surprised at how RAF fighters seemed to always be right where they were as they crossed the English coast. Because in Germany at that time, radar was so Top Secret that the Luftwaffe didn’t even tell their aircrews about it. They only learned about its existence when the Luftwaffe began putting radar units on their own night fighters in 1942.

By that time, the RAF had been using HF radar units on Beaufighters and Mosquitoes for almost a year and a half.

cheers

eon

There are probably no parts of a simplified rifle that are compatible wit a P14 or derived from it.

You neglected to mention that the Garand also went from 4 grooves to 2 grooves during WW II (Hatcher’s Book of the Garand p 160). I was quite surprised by the omission as it was your video featuring the book that led to my getting a copy along with the biography of John Moses Browning.

While I knew the history fairly well, my recollection was that the development went through more iterations than was actually the case. Garand was not as prolific as Browning, but I think every bit as good and arguably better in producing a design ready to manufacture.

“R.O.F.” stands for Royal Ordnance Factory, and ROF Fazakerly was just one of those.

The curved buttplate has always seemed to me a waste of resources. A flat cut and a flat plate would work fine.

There was also a simplified barrel with the “knox” form a seperate piece that was pinned to the barrel tube

This “simplification” looks somewhat half-hearted.

For example, the metal butt plate could be completely abolished, as the Germans or the Japanese did.

PS Finally some really interesting stuff.

Not “Forgotten Waste Paper”.

“War emergency” designs in small arms are nothing new. One example dates to the American Civil War.

The Maynard Carbine was introduced in 1859. It was one of the first metallic-cartridge single-shot rifles, using a separately-primed cartridge fired by a percussion cap or Maynard’s patented tape primer.

The First Model Maynard;

https://images2.bonhams.com/image?src=Images/live/2009-07/23/7903372-114-1.jpg&width=640&height=480&autosizefit=1

Was in every respect a high-quality civilian sporting arm. Note the tangent rear sight on the stock wrist (graduated to an optimistic 1,000 yards), the color case-hardened receiver with integral Maynard tape primer device, and the cast-brass buttplate assembly with an integral “patch box”, actually a receptacle for spare Maynard primer rolls, two to be exact. Not to mention the highly-varnished walnut stock.

Many First Model Maynards showed up in the hands of Confederate cavalry, due to pre-war purchases by several Southern states and a lot of private purchases.

By 1862, under the pressures of wartime production, Maynard introduced the Maynard Second Model, which was for the Union Army cavalry;

https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/proxy/SqoFFeiFyWaAjxlHcmNLcWtDyckeX4kqMl40yrltMWergH4SBYWog1JEgCBJnpQ3W3yqK141ZZ-zxQltX7IA84AAZ84n

https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?id=NMAH-ET2012-13886&max=1000

About the only “luxurious” feature of the First Model remaining is the case-hardening of the receiver.

The tape primer is gone. So is the cast brass buttplate assembly. A simple stamped wrought iron buttplate has replaced it.

The tangent rear sight is gone. Note the simple flipover two-position rear sight on the barrel breech. The two “leaves” were set for 100 and 200 yards, which is a much more “accurate” assessment of the .50 Maynard’s accuracy capabilities. In fact, the sight bears a remarkable resemblance to the “expedient” rear sight on the Rifle No. 4 eight decades later. Or most SMG rear sights of the WW2 era, for that matter.

And the stock was given a simple linseed-oil finish, and was as likely to be made of beech or even oak as walnut.

The Second Model Maynard was just as effective a weapon as the First Model. It was just faster and cheaper to build.

It should also be considered that, myth to the contrary, the average soldier of the 1860s, in any army, with a .58 rifle-musket probably couldn’t hit much of anything beyond about 250-300 yards with it, except perhaps in volley fire Brown Bess style. So instead of the complex ladder-type rear sights graduated to 800 yards or more that were standard on Springfields and Enfields, the armies of the era could have saved themselves a lot of time, trouble and money by specifying rear sights like the Maynard Second Model’s, or the Rifle No. 4 “emergency” type, on their standard rifle-muskets.

A leaf set for 100 yards and another for 250 or 300 would probably have been “close enough for government work”.

cheers

eon

https://collections.royalarmouries.org/battle-of-waterloo/arms-and-armour/type/rac-narrative-557.html states that “1777 system” spawned simplified Model 1777 corrigé AN. IX système. without giving further details. I am not expert at 18th century fire-arms therefore I ask: was were changes? how these influenced time need to produce 1 example?

According to this;

http://www.centotredicesimo.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Moschetto-M.1777-corr.An-IX-Gazette-des-Armes.pdf

The “corrected” model was introduced in Year 9 of the New Order (1800) at the order of Napoleon. The changes were;

1. A shorter blade on the epee’ bayonet.

2. A simplified lockwork and lockplate.

3. Cast iron barrel bands instead of cast brass ones.

4. A shorter barrel and overall length.

Note that most parts were interchangeable with the prior standard M1763 musket. As such, as muskets went through the equivalent of IRAN (Inspect and Repair As Necessary), any combination of “old” and “new” components might show up on any musket.

cheers

eon

The decision by the UK establishment in the Napoleonic Wars to emphasize the so-called 1793 or 1819 “India pattern” “12-bore” Tower muskets instead of, say, the short land pattern or the 1804 New Land Pattern…