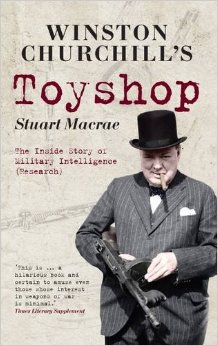

In July of 1939 Stuart Macrae was the editor of Armchair Science magazine, and he was approached by a Major Millis Jefferis from the British War Office looking for some information on magnets. The subsequent partnership between these two men would lead over the next 6 years to a hotbed of weapons and demolition production and design to rival anything else establish during the war. The Ministry of Defense I as it came to be designated was an outside-the-normal-channels institute that reported directly to Prime Minister Churchill and was responsible for developing, prototyping, and manufacturing (or contracting for the manufacture of), basically, any clever and destructive gadget they thought would be useful in the war effort.

In July of 1939 Stuart Macrae was the editor of Armchair Science magazine, and he was approached by a Major Millis Jefferis from the British War Office looking for some information on magnets. The subsequent partnership between these two men would lead over the next 6 years to a hotbed of weapons and demolition production and design to rival anything else establish during the war. The Ministry of Defense I as it came to be designated was an outside-the-normal-channels institute that reported directly to Prime Minister Churchill and was responsible for developing, prototyping, and manufacturing (or contracting for the manufacture of), basically, any clever and destructive gadget they thought would be useful in the war effort.

The first product of this shop was basically created by Macrae and a friend in his garage and tested in his bathtub – it became known as the Limpet and would be used to sink more than a few ships in cloak-and-dagger raids. The idea was a mine attached by a swimmer to the hull of a ship using several powerful magnets, and trigger by a time-delay fuse.

With the Limpet a rousing success, Macrae and Jefferis’ organization began to grow, and would eventually produce dozens of different successful weapons. These included several triggering mechanisms for sabotage work (called Switches in British ordnance parlance) – pull (tripwire), release (removal of a weight from the trigger), pressure (such as under a railway track), aero (triggered by altitude), and more, designed to trigger a detonation by nearly any conceivable method.

MDI would also design a number of mines and bombs, including anti-personnel bombs which would hit the ground and then jump back up into the air 15-20 feet before detonating, so as to get the lethality advantage of an airburst without relying on a timed fuse or altitude fuse (and thus making them universally applicable).

For readers of Forgotten Weapons, the most recognizable product of MDI will probably be the Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank or PIAT. This was a spigot mortar firing a roughly 2-lb shaped-charge shell for use against German armor. The principle of the shaped charge warhead (now common in anti-tank weapons) was that a cone of explosives, when properly sized and held slightly off the intended target, will create an intense directed blast rather than a simple explosion. This blast is capable of drilling a small hole through quite thick armor plate and disabling a tank. Because the intensity of the blast is dependent on the geometry of the explosives rather than kinetic energy, such a shell can be completely effective when fired at low velocity. MDI used this principle to build the PIAT, which would launch such a warhead using a propelling charge in the base of the shell and a large coil spring to propel the round into the air (and absorb some of the recoil from firing). A thoroughly unconventional weapon, the PIAT proved effective despite its quirks, and more than 100,000 were built and issued by the end of the war.

What really makes Winston Churchill’s Toyshop an outstanding book is the writing, though. Macrae does a marvelous job of drawing you into the story of the institution, and his sense of humor will really hook you. Whether it’s his description of gaining an undeserved reputation as a sexual athlete for buying up all the condoms in the town (which he was using to experiment with waterproof fuses) or his tricks for bypassing and bamboozling bureaucracy (like completely fabricating raw material contract numbers, later to find them listed in official Supply Ministry paperwork as “top priority” after the war), Macrae really has a knack for making potentially incredibly dull subjects entertaining to the least enthusiastic reader. His history of MDI will draw you in and make you really appreciate the accomplishments that a group of talented and motivated people can achieve when they are cut loose of red tape.

I once had the oppertunity to fire a PIAT. that was 3 times: The first, the last and the only. my scholder didrny breake of, it just felt like it.

The principle of the reverse-cone shaped charge, from which nearly all chemical-energy HEAT rounds derive in one form or the other, is universally well-known. Other less well-known shaped charges, eg., the Beehive Charge, used primarily for penetration of hardened bunkers, also operate on the same principle whereby the concave shape of the cone of the liner inside the warhead focuses the full energy of the hyper-velocity, small-diameter stream of molten metal as said cone melts in the brief nanoseconds of detonation.

While improvements in technology , eg., higher-grade cone and warhead liner materials, more powerful and suitable warhead explosives, tandem HEAT warheads and quicker-reacting fuzing, have resulted in improved armor penetration, it should be noted that — assuming all else is equal — HEAT warhead designs of every kind still have to subscribe to two basic tenets induced by the laws of physics: The effective diameter of the cone ( and therefore the warhead ), and the stand-off distance matched to that particular warhead.

With a little experimentation, it is also relatively easy to build your own improvised shaped-charge warhead out of an appropriate quantity of commercially available or surplus military plastic explosive ( C3, C4, Semtex, etc. ), an electrically-primed or fuse-operated detonator, and an old metal coffee can. This sort of improvised shaped charge has been used for decades in the military, mining, construction, offshore engineering and commercial diving fields when factory-made devices have not been readily available.

As a proviso to the above-mentioned paragraph, please do not attempt to build and operate such a device without proper training, safety awareness and appropriate legal approval.

Earl, your description of how a shaped charge works is fundamentally flawed.

A shaped charge, of any nature, uses the principle known as the Monroe Effect, which one Charles Monroe first observed while working for the US Navy. He recognized that the concave lettering stamped into blocks of guncotton were reproduced in the steel target they were laid upon. Later experimentation showed that this effect was reproducible, and it was first written up during the late 1880s, and was later published around 1900 in Popular Science Monthly. Later, a German by the name of Neumann discovered that while a simple block of TNT would dent a steel plate, creating a cone-shaped cavity in it would cause the same charge to cut the plate.

The cone does not “melt”, nor is there any recognizable burning effect taking place. What essentially happens is that the cavity itself allows the detonating explosive to focus the blast wave as it propagates down the charge from the point of detonation, which must always be top dead center of the charge. This focusing will take the charge liner, and essentially turn it inside out, creating a spike of material that is driven at such high speed into the target that both the spike and the material are made plastic to the point of liquidity. There is no burning, no melting taking place. In the milliseconds of the blast, there is no time for that. It is simply the focused pressure of the blast wave doing the work. Were the effect of such warheads to rely on heat and burning to do their work, the energy from these warheads would dissipate long before penetration took place. No doubt you could penetrate armor with such a technique, but you’d basically have to hold the flaming warhead against the armor for as long as it took to burn through it, which would probably be on the order of several minutes.

If you took a thermite grenade, and sat it on top of a V-8 engine block, it would eventually burn through the block after about five to ten minutes, depending on conditions. That would be an example of you could call a “melting” penetration. On the other hand, you could take a shaped charge, and drive a rod of cone liner material through the same block in milliseconds, using the shaped charge effects. No “melting” takes place; simple high-pressure physics, and what would best be likened to explosive ju-jitsu, as the effect of the explosive is vastly increased by focusing it on one tiny spot of the armor, instead of spreading it out over the entire surface, as the same amount of explosives without a shaped-charge cavity would.

Hi, Kirk :

You are correct in your description. I have worked with explosives and demolition charges, both topside and underwater, for a long time, and actually meant to say pretty much the same thing, but somewhere in the editing I deleted a couple of lines in my description summary and changed the entire meaning! Serves me right for being in a hurry and not cross-checking thereafter. Thanks for catching my slip-up.

Is that a reprinting? I see a version from the 70’s on Amazon.

Yes, it’s a reprint, and was originally published in the 70s.

I remember this book in my local library some twenty five or more years ago; the librarian let me take it out on a young adults ticket.

Some of the devices described reflected the parlous state of Britain’s defences and the desperation immediately after Dunkirk. No significant anti-tank weapons (most being left on the beach) resulted in inventive, if marginal, solutions. The Blacker bombard (a static precursor to the PIAT)- salted along the various stop lines in Kent and London itself, the Smith gun- essentially a drainpipe on a carriage axle which flipped onto its side to enable a horizontal field of fire, and the sticky bomb (a product of the Toyshop). The ‘toffee-apple’ bomb (or candy-apple, for Americans!) was produced in its millions and universally regarded as suspect- believed to be as likely to stick to the operator as the target. The throwing handle (akin to the classic German ‘potato masher’ grenade) was believed to pose a projectile threat to the operator on detonation, and in a bizarre- or humdrum- safety test the explosive filling was slathered onto a hinge which was rotated thousands of times to see if it would detonate through friction- as the metal casing holding the glass sphere (!) containing the sticky membrane and warhead was hinged and to be removed for deployment. Never issued to regulars, but a component of the Home Guard arsenal. An interesting sequel to the poorly regarded (in terms of their likely contribution in the event of invasion) Home Guard has recently come to light- Auxillary Units; essentially secret suicide squads whose first job following invasion was to assassinate the police officers who had originally recruited them to ensure operational secrecy!

One idea that was quickly dismissed as perhaps too beastly to be used even on the Wehrmacht was the ‘castrator’, a .303 cartridge in a tube, pushed at a slight angle into the ground and to be detonated by standing on it- foot wound certainly, sticky mess in the trouser area likely. Ugh.

The PIAT has been described to me by vets at the VA as: A weapon that is dangerous to everyone everything be it friend or foe. More then one account of it leveling trees, buildings and misfiring in some shape form, the best that has been told to me is it bouncing off a tank and going off in the air leaving a smoke trail to the poor man who fired it. also would take an ear or cut a smile into your face.

Also had my grate uncle talk about the sticky bombs being around in north Africa and as he put it left in the sand by the British because it stuck to everything and had a short fuse.

@ William Brown, I am pretty sure that there was no smoke trail from the grenade as it was not propelled by a rocket engine.

It was propelled by a cartridge embedded in the launch tube forcing the grenade to leave the spigot.