For a while now I’ve been following the rabbit hole of machine gun use in the second half of the 19th century – the days of the manually-operated machine gun (Gatling, Gardner, Nordenfelt, etc) and the early days of the Maxim. The persistent question is, why didn’t anyone seem to recognize the military potential of these new weapons? Why, after literally 50 years of exposure to automated firepower, did Europe send a whole generation of young men walking into masses of them?

For a while now I’ve been following the rabbit hole of machine gun use in the second half of the 19th century – the days of the manually-operated machine gun (Gatling, Gardner, Nordenfelt, etc) and the early days of the Maxim. The persistent question is, why didn’t anyone seem to recognize the military potential of these new weapons? Why, after literally 50 years of exposure to automated firepower, did Europe send a whole generation of young men walking into masses of them?

Well, David Armstrong does an exemplary job answering this question for the United States in Bullets and Bureaucrats: The Machine Gun and the United States Army, 1861-1916. Drawn heavily from period reports, official correspondence, and other primary sources, Armstrong shows how and why the US Army failed to understand how to make use of these new arms. The writing is dry in places (though not nearly as much as one would expect given the subject matter) but overall engaging, and refreshingly free from hyperbole – except when quoting some of the colorful personalities involved in the story, like Captain John Henry Parker.

The two dominant factors that lay in the path of sensible machine gun doctrine for the US were a small mostly-peacetime military budget and a lack of interest in finding the useful role of the guns. With the gift of hindsight we can clearly see today how machine guns can be used in all manner of military maneuvers, but in the latter half of the 1800s those roles were completely novel. The early manual guns like the Gatling were heavy and bulky, and thus mounted on artillery carriages – and this led to them being treated like artillery. They were considered poor performs because they were compared to large-bore guns firing canister shot, and tended to be deployed to forts where they were carefully stored to prevent wear or damage – virtually no ammunition was supplied for training with them, so nobody was able to learn how to use them effectively.

By the time the Army finally started to open up its collective mind to the tactical possibilities in the first decade of the 20th century, the whole process hit a wall with the adoption of the Benet-Mercie. It was adopted after a brief trial because it was far more portable and faster into action than the 1904 Maxim. Only later once the decision was made was it realized that the Benet-Mercie was severely limited in effective accuracy and rate of fire compared to the Maxim. The Army went from the mistake of using machine guns as artillery to the mistake of using an automatic rifle as a heavy machine gun. By the time this was corrected and the Army adopted the Vickers, it had become impossible to get them from England because of the ongoing World War. And thus American troops arrived in France with a few Benet-Mercie guns, no experience, and practically no training with them.

Anyway, this is the story which Armstrong tells in superb detail, from the days of Ordnance Chief Ripley (who said “no” even more than Calvin Coolidge) to the War Department’s inability to even find out the details of machine gun usage in the Great War until it was too late to do anything about it. For anyone interested in the history of US military small arms, this is definitely a book you should have in your library.

Predictably, it is out of print – but there are lots of copies available used. As I’m writing this, Amazon has one for less than $6, and then a half dozen more in the $25 range. Whoever gets there first can snag the cheap copy. 🙂

Well, the Amazon one was gone, but 6.35 on Ebay wasn’t too bad.

The other night, I came across my copy of “The Social History of the Machine Gun”, a very good book which covers similar material, but from a broader perspective which includes the major European powers. As I recall, the author pointedly notes the paradox of European armies apparently believing that White soldiers were somehow immune from the effects of the very same machineguns that they’d been using for over a decade to scythe their opponents like corn in various colonial conflicts (plus the Boxer Rebellion and Russo-Japanese War).

You mean this book?

https://www.forgottenweapons.com/book-review-social-history-of-the-machine-gun/

🙂

Yep, that’s it. It’s a very good book.

The only way I can think of to start this is with a handful of questions.

They’re going to seem pretty contentious, the purpose isn’t to start an argument from previously held (and probably received)positions, but to try to think this through. I really don’t know the answers or how to start to think this through.

Why were there armies in the 19th century – after Napoleon was safely onto St Helena, it should have been a period of free trade and increasing prosperity – Winston Churchill, in his “My Early Years” lammented that during his officer training in the 1890s, the general belief was that the proper nations of the world were too civilized for there to be a proper war, why were there still armies?

what is a centrally planned army actually useful for?

The US founding fathers understood what the Somali, Afghan and Iraqi civilians (and arguably the Libyan, and Syrian too)have been demonstrating in recent years, that a few committed civilians with rifles and maybe a few RPGs, are more than a match for even the worlds biggest and best funded armies, why then the expense of having the centrally planned chaos that is a standing army?

back in the Advanced combat rifle thread, https://www.forgottenweapons.com/us-advanced-combat-rifle-video/ I’d started questioning the extremely low opinion of soldiers, held by the weapons policy people – basically assuming that if soldiers actually encountered armed opposition, they’d panic – a view which has empirical evidence to back it up – we’ve also seen the same thing with twitchy fingered cops over the last couple of months

– if, in reports for internal military use, the armies themselves admit the inadequacy of their selection and training to turn out soldiers who are steady under fire, or when they meet actual soldiers in combat

then what is the actual purpose of an army, and of such inadequate military selection and training?

I know this is a very old comment, but all the same, i think there is a mixture of reasons to have a fairly large standing army;

1) If you are turning over enough soldiers you will identify the small percentage that do have the character traits and skills, allowing you to cream them off into your special forces -which carry out the majority of actual significant (in terms of results) actions (certainly in the modern age -i’m not sure how this applied in the era you refer to, but i suspect it still did).

2)Logistics -you need to move a lot of gear (a lot of it very heavy) to engage an enemy on any scale, in ‘modern’ warfare -you need to have the infrastructure and people who know how to use it / move it -it isn’t all front line work in the army.

Though this does come right down to moving troops -your guys need to be used to using whatever means you are going to deploy them with -helicopter, plane, APC -a lot of soldiers get injured disembarking on their first deployment -they are nervous / on edge, jump from a helicopter before touch-down underestimating undergrowth depth, or jump before the ramp is all the way down on the military transport plane -but i’d imagine you get even more injuries if your soldiers hadn’t done this for years.

3)Deterrent.

I guess its a bit like bullets -they are the least affective part of the military arsenal -i can’t recall the statistic -numbers from 25 000 to 250 000 per kill come up depending on the conflict, but they still play a lot of other roles -rounds fired by your side intimidate your enemy, boost your guys confidence, and more directly can suppress the enemy or even deny occupation of an area.

Your soldier feels more confident with bullets in their gun -and even if they aren’t natural born killers, they are still more likely to kill with a rifle than a knife or their bare hands, because it gives a degree of detachment. I guess what i am trying to say is there are more hard to quantify elements than actual effectiveness statistics.

And your RPG guys are going to fight harder than your average -because everybody fights harder, when they have their backs against the wall -if you believed your family or friends were going to die or be abused, or that their only chance of having a good life is if you win, you will fight hard. RPG guy probably knows the terrain he’s fighting in pretty well too.

Bullets and Bureaucrats. Sounds like the setup for a ‘The Great Karnak’ sketch. Interesting you should mention Captain John Henry Parker. His book (The Gatlings at Santiago) is available for free on Google books.

Link here: http://books.google.com/books?id=G8ycHMg3g3cC&printsec=frontcover&dq=HISTORY+OF+THE+GATLING+GUN+DETACHMENT+FIFTH+ARMY+CORPS,+AT+SANTIAGO&hl=en&sa=X&ei=2zpwUciqJofB4AOvloDwDw&ved=0CDAQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

I have not had a chance to read it yet, but I assume it is a great reference

I haven’t read either book (the subject of the thread, which at the moment is more like $70 on Amazon, or Capt. Parker’s. Some time ago I did a post on early US MGs based on a Military Review (? I think) article by Col. (R) Parker Hitt. As a young 2nd Lieutenant, he implemented the 1904 Maxims and had a shoot off with Capt. Parker, who was known in the service as “Gatling Gun” Parker. Parker was quite astonished that Hitt’s Maxims could put more rounds on target than his Gatlings.

I kind of hate to come over here and blow my own horn, but if you like this subject matter you may like the links in my post.

http://weaponsman.com/?p=6623

Thanks for the link, Kevin. I really enjoyed reading the article.

The idea of the time was a small standing army to serve as cadre for a rapid influx of untrained troops. That worked well as long as the main job was “march somewhere, load rifle, stand still, fire”, especially if most recruits had experience with guns, so all you had to get them to do was “stand still” (not always easy if the other guy is coming at you with a bayonet). The first to see the flaw in the system with a much more technical and mobile warfare, with trains allowing for rapid shifts of armies, were the Prussians with their conscription during peacetime as training for the Landwehr system of reserves. This enabled them to fill their army with quality troops in a very short time (see Denmark, Austria, France for how not to). The US, sitting on the other side of the ocean didn’t get the message, and continued to rely on militia recruits to fill their ranks in case of emergency (which didn’t happen until 1898). The main lesson the US learned from that war was that Mauser rifles were a good thing to have, but machine guns weren’t that important as it was still a pretty fluid war. I think the Japanese-Russian conflict and the siege of Port Arthur were the first time the superiority of the machine gun in entrenched warfare was obvious, but again, that was a long way from the US or Europe for that matter.

Ian made a good point about how the early machine guns tended to be treated and employed as light artillery by ( the unfortunate ) virtue of their being mounted on field carriages. One of the earliest examples of this failure to understand the potential role of the machine gun and its ability to influence battlefield events was during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. The French Army had adopted into service in 1869 a number ( reportedly 156 ) of the Montigny Mitrailleuse, a 37-barrel battery gun originally designed by Belgian Captain Fafschamps in 1851 and subsequently built at the Meudon Arsenal ( it should be noted at this point that some sources state that the Montigny Mitrailleuse in French service had 25 rather than 37 barrels, and that the latter was an upgraded version exported to Austria for use in fixed defensive fortifications). During the 1870 War, the Mitrailleuse performed poorly, but this was proven to be due not to the mechanical or operating aspects of the gun, but to tactical misemployment. They were handled as artillery and brought into action side by side in open positions at extreme range, with the result that the Prussian artillery, which outranged the Mitrailleuse anyway, simply stood off and pounded them into scrap. In contrast to this, on the few occasions that the Mitrailleuse were handled imaginatively with proper siting under cover and good fields of fire, they inflicted a lot of casualties on the enemy in a relatively short time. It was fortunate that the French Army recognized the failures as stemming from misemployment rather than operational issues, and so the concept of the machine gun survived in French military doctrine.

Actually, the dismal performance of the Mitrailleuse in 1870 more or less led the French high command to ignore machine guns for the next couple decades. It was only around 1900 that they finally caved to growing political pressure to equip the French army with modern machine guns. You are correct about the reasons for their poor performance, though – doctrine called for them to be used as counter-battery artillery, which was definitely not an effective use.

From what I have read from different sources, while it is true that the French High Command did set aside the concept of the machine gun for the next several years after their negative experiences, there was apparently a minority of senior officers who never entirely discarded it either. It was just enough to keep the idea alive if dormant until the political climate changed.

AFAIK, the French did not use the Montigny Mitrailleuse, but the competing Reffye design, which did, in fact, have 25 barrels.

Ah, that explains the discrepancy and the conflicting accounts — thanks!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mitrailleuse

The link explains the development timeline of the Mitralleuse in French service quite clearly, and helps to show why there has been some confusion in the past concerning service use of the Montigny and Reffye guns — thanks, Fidel.

As much as machinegun played important role in war it looks in retrospect, that it was field artillery, specifically howitzers who had upper hand and often called shots. There are countless of testimonies (today just recorded history) from surviving soldiers on the subject. I believe that top commands must have expected just that. And since the artillery was not sufficiently mobile, the fronts became bogged down.

Does anybody know, how was in that respect equipped U.S. expedition corps to Europe?

I agree with Mu’s observations about the Prussian Landwehr system as well as the Russo-Japanese wars regarding lessons to be learned about the proper employment of the machine gun on the battlefield.

A positive long-term spin-off of the Landwehr system was the ability of the German soldier to still function efficiently when grouped in ad hoc battle units with unfamiliar officers and NCO’s. On the other hand, American, British and French troops were less likely to perform well under similar circumstances when removed from their parent units due to the Regimental system. There are pros and cons concerning the two systems that could be endlessly discussed and debated ; both have certain strengths and weaknesses depending on how the problem is approached.

On the second point, it was the German Army that pioneered more effective usage of available machine gun assets in World War One. They placed all six heavy MG’s alloted in the standing Table Of Organization & Equipment ( TO & E ) of a three-battalion infantry regiment directly under the command of a Regimental Machine Gun Officer, who had the discretion and flexibility to employ them as he saw fit. All the guns could therefore be brought into play to support a single battalion at a critical point if needed, and this flexible use of existing assets as a force multiplier convinced the Allies that the Germans had far more machine guns than they actually possessed. In contrast, the more parochial Regimental system adhered to by the British and French meant that each battalion was solely responsible for its organic MG’s and their deployment ; in practice, this meant that a battalion involved in a heavy engagement would be using only its own MG’s and could not rely on the support of an uninvolved sister battalion’s MG’s, regardless of whether they were physically available or not.

To their credit, the British later took the process a step further by removing all the Vickers MG’s from the infantry battalions and placing them under centralized control in the Machine Gun Corps Regiment, which could then assign the guns in batteries as they saw fit. This provided intensive concentrations of supporting heavy MG firepower to the infantry units as needed.

Denny has a point about the machine gun versus artillery. One historical myth that still persists in the popular imagination to this day is that, during World War One, the machine gun was the chief culprit in battlefield casualties sustained through enemy action. As a matter of fact, statistics indicate that the British Army suffered 38.9% casualties from rifle and MG fire combined, while artillery accounted for 51.5%. Figures for other combatant nations tell a similar story, although the American Expeditionary Force experienced less extreme casualty ratios due to the more mobile nature of warfare late in the conflict.

Statistical studies from World War Two and every subsequent major war since then tend to bear out the same basic conclusions, with some variation in the machine gun versus artillery ratio due to circumstances.

I appreciate that the subject is machinegun, but as you say, all and any means of destruction had their role including just born airforce (and they used plenty of them).

I recall from tales told by my granpa who was stationed first in Roumania and later on Italian front, that artillery was omnipresent and pesky (if it was enemy’s) phenomenon. Italians surely knew how to use it.

Wasn’t the Benet-Mercie machine rifle ( Hotchkiss Portative Mle 1909 ) originally developed in anticipation of the introduction of more mobile battlefield tactics early in the 20th century? Certainly, the light weight and automatic fire capability aroused the interest of the French, British and U.S. cavalry, who bought numbers of the gun. I also seem to recall that the Mle 1909, equipped with a special strip feed holder, was the first aerial gun to be used by the French Air Service ( Aeronautique Militaire ).

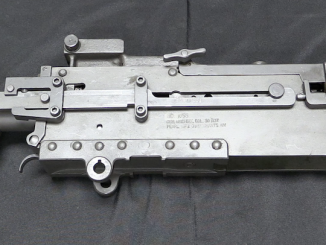

Yeah – it was originally adopted after a short cavalry trial, which (no surprise) found it much more mobile and suited for cavalry use than the 1904 Maxim. However, the Army decided to adopt it for both cavalry and infantry services after that trial, which was a big mistake. While a reasonable compromise for cavalry, it was much inferior to the Maxim for the more static, long-range infantry use.

Col. Parker K. Hitt mentions in his article that the Maxim was replaced by the Benet-Mercié, “and that is another story.” If he did tell that part of the story in another article, I haven’t got a grip on it yet.

The French CO Abdel Douay was killed, when the Krupp cannons hit a stash of Reffye reloads, and the rest is history.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Wissembourg_(1870)