We shot this video a while back, and it’s not as complete as I would like – but it’s still a good intro to a post on the Australian Owen SMG…

(and yes, I misspoke when I said that the Sten didn’t have a semi setting – semiauto was actually fairly common on submachine guns by this time)

The Australian-designed Owen submachine gun is a weapon with quite a story behind it. The Owen is arguably the best subgun used during WWII, and also probably the ugliest. Its mere existence was a drawn out struggle between the inventor and manufacturer and the Australian Army bureaucracy, and yet it saw service through into the Vietnam War.

History

The Owen gun story begins with a young 23-year-old Evelyn Owen and his incessant tinkering with guns. In 1938 he perfected (well, sort of) a homemade full auto carbine firing .22LR from a drum-type magazine. It used a thumb trigger instead of the normal type, and was thoroughly unfit for military use. He showed the gun to a some Australian Army officers in 1939, and was (not surprisingly) turned away – the Army was not interested in new submachine guns in general nor Owen’s contraption in particular. By 1940 Owen had lost enthusiasm for the gun, and enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force.

That would have been the end of the story if not for a happy accident. Shortly before deploying for military service, Owen haphazardly left his prototype gun in a burlap sack leaning against the house – where it was subsequently found be a neighbor (Vincent Wardell) who just happened to be manager of Lysaght Works, a metal fabrication firm. Wardell was curious, discussed the gun with Owen, and convinced him to demonstrate it to the newly formed Army Central Inventions Board. The Board commander , a Captain Cecil Dyer, was interested (the Battle of France having been recently lost, and Britain’s ability to prevent German invasion in serious doubt), and the result of the demonstration was Lysaght’s agreeing to develop an improved centerfire version. Owen left for his deployment, and development of the gun was undertaken by Vincent Wardell, his brother Gerard, and a gunsmith in their employ named Freddie Kunzler.

At this time, most of the Australian Army officialdom was anticipating adoption of the Sten gun, plans and models for which had been promised to them by the British government. The Sten was purported to be a much better gun than experience would eventually show, and the establishment didn’t want to muddy the waters with competing designs with no provenance. In an effort to scuttle the newcomer, the Army told Lysaght to provide a sample gun for testing, chambered in .38 S&W (and neither ammunition nor a barrel was to be provided for factory use). The specification of a rimmed cartridge was expected to stump the Wardells, and was indeed a challenge not undertaken by any previous successful SMG design. So they sidestepped it, and made the gun in .32ACP instead, using a section of an SMLE barrel. This prototype was delivered to the Army in January 30, 1940 – after just 3 weeks of development. It fired effectively and reliably, and the Army requested a 10,000-round endurance test. They would not supply the ammunition, and in wartime Australia that quantity was effectively impossible for the factory to acquire. Instead, Lysaght’s built another gun in .45 ACP, having been assured that plenty of ammunition would be available for this (they assumed it would be from stocks supplied for Australian Army Thompson guns). But when the ammunition arrived at the factory, it turned out to be .455 Webley ammunition instead – so they went back again and retrofitted the gun using a section of old Martini-Henry barrel.

Around this time Evelyn Owen was recalled from field duty and assigned to work with Lysaght on the gun development, although it is unclear when design elements were his contributions and which were brought by Wardell and Kunzler. The Army efforts at scuttling the Owen gun continued, and it was only through Vincent Wardell’s persistence and willingness to go directly to civilian politicians that the gun finally came to be accepted. It had passed mud and dust testing with exceptional results in both .455 Webley and .38 S&W (the first 100-gun order was again demanded to be in .38 S&W by the brass). Only in early September 1941 was a 9mm version authorized, and this by a civilian official tired of Army obstructions.

The turning point for the Owen was a competitive trial at the end of September 1941, in which it (in both 9mm Parabellum and .45ACP) was pitted against a newly-arrived Sten and a Thompson. The Thompsons did well when clean but not so well when dirty, and the Sten quickly failed in sand and mud tests. The Owen passed with flying colors, in both calibers. This led to an order for 2,000 9mm Owen guns for field trials, and the rather impertinent sending of Owen gun samples and drawings to England, with the suggestion that the Sten be discontinued in favor of it (and in a 1943 English test, the Owen beat all comers, including the Austen, Sten, and Sterling).

Mechanics

The Owen was a fairly simple open-bolt design, but it incorporated a number of creative elements that made it superior to other contemporary guns.

First of all, it utilized a top-mounted magazine, which gave several benefits. It allowed gravity to assist both feeding and ejection (although the Owen will function when held upside-down). Since the ejection port was on the bottom of the receiver tube, dirt which might enter form the magazine or through the magwell would often just fall right through, having no place to collect.

Second, the Owen used a two-chamber receiver. The bolt cycles in the front chamber (with a relatively short travel), and the charging handle is located in a separate chamber in the rear of the receiver. Only a small hole between the two allows the charging handle to connect to the recoil spring guide. As a result, and dirt entering through the charging handle slot is confined to the rear section, where it cannot do much to impede the gun’s function. There is no way for gunk to get behind the bolt, where it is most apt to cause problems.

Because of this design, disassembly is done from the front – unlike most open bolt subguns. The barrel is easily removed by pulling up on the barrel pin at the front of the receiver. The rear end of the barrel and the front of the receiver tube are machined with tapers, so the barrel is easily seated in place. Once the barrel is removed, the bolt and recoil spring slide out the front of the tube. In most guns, this would be obstructed by the ejector, but in the Owen the ejector is made part of the magazine rather than integral to the gun itself. As the bolt extracts a fired case, it holds the ammunition in the magazine down (well, up, given the top-feed arrangement). After enough rearward travel, the rim of the empty case hits the ejector tab at the rear of the magazine, which tips it out of the extractor to drop free of the gun. Pressure from the next round in the magazine, now pushing directly on the empty case, provides additional ejection force.

Handling

The Owen is a very clumsy looking gun, but handles better than you might expect. The grips are well placed, the weight (9.5-10.5 pounds, depending on the version) and built-in compensator at the muzzle help to keep the gun controllable. The safety and magazine catch are both simple and effective (although the original fire selector apparently had a tendency to allow bursts when in semiauto mode). To allow for the top-mounted magazine, the sights are offset to the left side of the gun – not a problem for a right-handed shooter, but a bit of a handicap for lefties.

The stock design is not particularly ideal, and is somewhat reminiscent of the Thompson (I have no evidence to prove it, but I would suspect this was deliberate, since the Thompson was the SMG in official Australian service when the Owen was being designed). Combining the Owen’s positive features with a stock design more in line with the bore could have made for a very interesting gun (in fact, the Australian F1 SMG that eventually replaced the Owen did this to some degree).

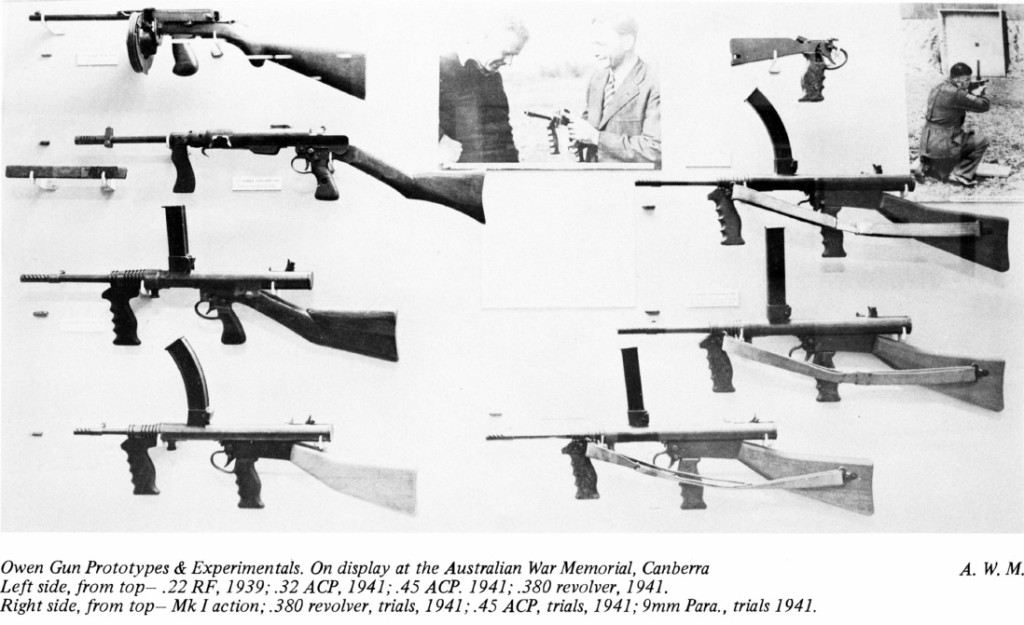

Variants

The Owen went through several changes, although the basic mechanism remained the same throughout production. The main goal of the changes was to reduce the weight of the gun, and they were able to take more than a full pound off of it this way. Guns made during WWII were painted with a camo scheme of green and yellow for jungle use, which is often seen on guns today. After the war, guns that were arsenal refurbished had the paint stripped off and were parkerized.

The two main versions are the Mk1 (roughly 12,000 made) and Mk1* (roughly 33,000 made). A MkII version was designed, but only a few hundred made. In theory, parts between all the Mk1 and Mk1* guns are interchangeable, although factory QC was not always tight enough to make this true in closely fitted parts like barrels. Over the course of war use and several decades of official adoption, many existing Owen guns will have a mixture of parts from different official types.

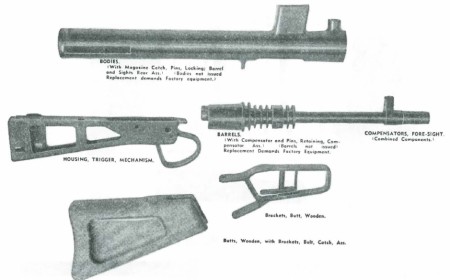

The main parts that were changed were the trigger housings, barrels, and buttstocks.

The early barrels were quite heavy, and finned to aid cooling. Over the course of production they were lightened and the fins discarded. The slotted muzzle compensator remained a feature of all versions, though.

Trigger housings began as solid units, and were later lightened with cutouts to remove unnecessary material.

The original buttstock design was made of bent strip steel, and a later version was made with a clip to hold an oil bottle. Wooden stocks were also made, both solid and with lightening cuts and both with and without traps to hold cleaning equipment.

Center – Factory rebuilt Owen with Parkerized finish, plain light barrel, and wood stock

Bottom – Austen SMG

Legacy

The Owen was taken out of production in 1944, with 45,433 guns built. They would remain in Australian service until replaced by the F1 submachine gun (which we will cover in another article) in the late 1960s. Owens saw use in Korea and Vietnam, and were generally well liked by troops who carried them. The gun may have been heavy, but it was rugged and dependable.

Evelyn Owen, unfortunately, did not lead a happy life after the war. He became addicted to alcohol, and died a bachelor in April 1949. Aside from employment and salary, he received payment of about £10,000 pounds for his part in the Owen gun production (royalties and patent rights sales), which he used to set up a lumber mill. He did continue to tinker with firearms until his death.

- Evelyn Owen and his gun

The Lysaght Works began the Owen gun project as a patriotic endeavor to help ensure Australia’s survival through the war. Until the first major order for 100 guns in April 1941, the company funded all the development and prototype construction itself, not asking for reimbursement. When mass production was contracted, payment was agreed at cost plus 4%…but government payments were perpetually late, and Lysaght was not paid in full until 1947, three years after production ended. After making additional interest payments on loans that could not be paid on time because of Army delays in payment, the company ended up making approximately a mere 1.5% profit on the project.

Technical Specs

Caliber: 9×19 Parabellum

Mechanism: Unlocked (blowback)

Overall length: 32in (813mm)

Barrel length: 9.7in (247mm)

Weight (late): 9.3lb (4.2kg)

Magazine capacity: 32 (some sources say 33) rounds

Rate of fire: 700-800 rpm

Manuals

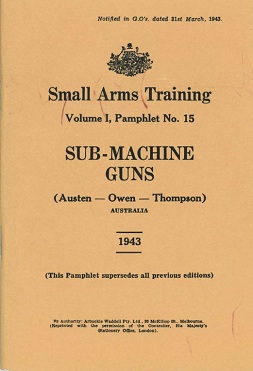

We have a copy of a 1943 Australian submachine gun manual, which covers the Owen as well as the Austen and the Thompson. It is short, but includes quite a bit of good information (note how doctrine at the time included shooting from the hip). You can down load it in PDF format here:

I wonder how often true patriotism has anything more than a spiritual reward.

Was that Uncle Bob’s Owen? I shot it in 2000, with Bob and Dolf, who brought me there. Kind of shakin’ while firing when seen on the movie, I never notices this magazine waving – seems pretty solid POV and and the range. VERY pleasant to shoot, I concur the opinion. Quite the opposite of the Austen, which was gov’t preferred, but didn’t seem to work 🙂

PS. This soundbite comes a bit garbled, but did you said that Sten HAS GOT or HAS NOT GOT the semiauto function? And frankly, the selective capability of the Owen is positively NOT a rarity, there were more selective fire SMGs in WW2 than full-onlies: MP 28 and copies (Lanchester, Sten, MP3008), PPSh 41, Reising, Thompson, PPD, Suomi, Mauser 712, Beretta, MP34oe, MP35 Bgm, Mors 39, Kiraly 39M – pretty all early-war guns were selective fires, only the MP 38/40, Greasgun and the PPS 43 were not. And of course there are self-mades: Błyskawica, e.g. was a full-only, but the BH44 was a selective fire, and the designer came to great pains to achieve that.

Yep, that was Uncle Bob’s gun.

And yes, I said that the Sten didn’t have a semi function, which is incorrect. Didn’t realize it until after the video was finished and posted (damn).

Hello all.. I was attached to 1 RAR while they were attached to the 173rd Airbirbe Bde Sep in 1965. I was the artillery LNO. The Owen was then their SMG, and SLR (FAL) their rifle and the Ausie’s loved the Owen. I had several opportunities to see it fire and fire it. It made you feel.. “this thing will do the job” and it did. A fine jungle weapon, even thought heavy.//Mike//

Owens are fine weapons. It is disconcerting when you fire it to see the magazine seem to wiggle around. This is due to the way the Owen extracts and ejects. The Owen is very accurate and one can hold and shoot it with one hand.just keep the but stock on. The later Australian SMG is a very good gun

for some reason the first thing i thought when i saw the slow motion part of the video was that i wouldn’t want to fire this gun when wearing something that has long sleeves

i can just see a couple of hot brass casings fly in the sleeve and burn me

is this the case or am i worried about nothing ?

Y’know, it wasn’t something that ever occurred to me as a potential problem. I didn’t have any issue when shooting, but I only put one or two mags through it. I think it would depend on your particular hold on the gun…

Have not had that happen with a OMC…but a L4 caught me that way once.

I have owned a couple of Owens (Mark 1 and a post-war Mark 2/3 modification). They are nice wee guns and quite rare now, even in this part of the World. A small number were made and successfully tested in .45 calibre and a tentative order was placed for 10,000 .45 guns to be supplied to US Forces in the Pacific but, sadly, nothing came of it.

There was also another advantage to having a top-mounted, top-feeding magazine — in close jungle warfare ( as was the Australian experience in places like New Guinea ), a top-mounted magazine helps a lot with hugging the forest floor as tightly as possible, thus maintaining a minimal profile and staying blended into the background and surrounding terrain, while still being able to manipulate and fire the weapon accurately. Additionally, unlike a side-mounted magazine under the same conditions, the top-mounted magazine is less likely to snag on brush and other cover.

Both the Owen and later F1 SMG’s were ( and still are ) superb, well-made guns that fulfilled their intended roles admirably. Like so many truly great weapons, they have not been granted the recognition they deserve due to the only too well-known circumstances of timing, politics and prejudice on the part of those who should have known better. The same applies to the designers and manufacturers of these guns who had the courage and foresight to pursue their case, only to be rebuffed by the powers-that-be for the same reasons.

very interesting and informative. Thanks!

That slo-mo was sweet!

Ian, any chance you could do a disassembly video?

Unfortunately, it’s not an option at the time being. I only had a short time with the gun when I took the shooting video, and it’s no longer available to me. If I can gte my hands on another one, I will definitely do a disassembly video, though.

I tried searching for the patent given on the poster.

no luck yet, I’ll have another try when I finish getting cold and wet in the snow.

Hey Keith,

I found it through the Australian IP office. I hope this link works: http://pericles.ipaustralia.gov.au/ols/auspat/pdfSource.do?fileQuery=%86%9F%A3%97%91%99k%A2%96%93T%94%97%9A%93%9C%8F%9B%93ko%83_gb_%5E%5E%60%60aep%5E%5C%9E%92%94T%A2%96%93k%9A%8F%A8%A7

Otherwise try their search function here: http://pericles.ipaustralia.gov.au/ols/auspat/

Thank you so much for presenting the Owen Machine Gun.

As a son of Australia, I have searched the internet for ages looking for live footage of the weapon my forebears used in New Guinea and throughout SE Asia. All I could ever seem to find was old grainy footage of some Diggers blasting away at a berm before heading off to Vietnam. I have seen a few static displays, and I know there is a working Owen at the Oregon Military Museum [Clackamas OR].

I recall reading several articles claiming the US Govt wished to purchase some 60,000 Owens for use in Asia and Pacific Island hopping campaigns, but the Austalian Govt turned down the request.

If you ever get to do make an Owen disassembly/assembly video, I’d love to see some more live fire footage, specially “from the hip”.

Thanks again,

Cheers, Robert.

The Australian War Memorial has an extensive collection of photos of the Owen in service as well as experimental variations. Try this search:

http://www.awm.gov.au/search/collections/?conflict=all&submit=Search&q=owen+gun

Nice to see this presentation on the Owen gun. It was certainly the preferred SMG for most Australian troops in the Pacific, my old man had a Thompson in New Guinea and an Owen later in Bougainville. He said the Owen was more reliable, but described his impression that the 9mm was not too powerful, and once said that he could have thrown the rounds himself for as much effect. I have handled Owens a bit but never fired one, they are certainly heavy and bulky, but comfortable to use when you have a good grip on it. I used an F1 a fair bit in training, and also felt that the 9mm did not have much power. The top-mounted magazine is great for quick reloading. Note that the sights on both the Owen and the F1 are offset to the right, not the left as stated above. The Bren gun has the sights offset to the left. By the time I got to Vietnam, Owens had been withdrawn, and F1s seemed to be a rear echelon weapon. The M16 had replaced SMGs for the most part, due I think to the fact that VN war firefights were often over longer ranges than in places like New Guinea, and also because an Owen or F1 against an AK was a bit unequal. My impression at the time was that neither the Owen nor the F1 were particularly popular with the infantry in VN, I think because of the disadvantage when up against an AK.

One of the main issues with the 9mm ammunition used in the Owens was that it was absolute crap. WW2 Australian made 9mm ammo was not good and, IIRC, that’s all the Owen was typically ever used with, even post war.

Ian, would you happen to be able to point to the reference for this point, “in a 1943 English test, the Owen beat all comers, including the Austen, Sten, and Sterling”? Do you have, or can you point me to, the original source? Thanks!

It is briefly mentioned in “The Guns of Dagenham” by Laidler and Howroyd – page 36.

Have a look at the link below – it shows the orginal trials against the sten. The owens shown are the prototypes (vertical cocking handle.

http://www.britishpathe.com/video/owen-gun-issue-title-is-account-rendered/query/Wet

I’ve seen footage with the production versions undergoing trials with sand being blown into the guns during firing. That footage shows Owen MkI, Sten and MP40. The owen was the only gun that kept firing. It also shows a guy field stripping the weapon. – worth looking for it

Carried one and fired it in anger. Its correct it didnt jam much, but it pulled something ferocious. The safety slide was an afterthought in WWII as the things had a habit of firing if dropped or bumped. You had to remember to release it and we were not to keen on doing that too early before a possible contact, in case we tripped.The face of the bolt also fouled up (may have been the ammo) but as a blow back weapon I guess thats pretty normal.

Mags were also a pain to reload, either the platform spring was as stiff as a car spring or as weak as hell…no middle ground. The other disadvantage was ammo…only a few blokes in a section or platoon had an Owen…if you ran out of ammo then you were pretty much snookered. With the normal grunts using .303 and or later in ‘nam 7.62, their ammo was like fleas on a dog.

Fired an Owen in at a weapon demonstration in Queensland as a School Cadet in about 1964, I was about 16 at the time and I remember that it was a very easy weapon to fire, had a climb but was controllable in burst and quite accurate in single shot. Had a go with a Bren using a carry strap standing, was ok as the weight held it down, only fired burst not continuous, for obvious reasons was not very accurate with the Bren this way. Great experience for young Cadets.

In the 1950’s Neighbor retired Army Captain Captain Ivor Rowe at Evelyn St ,South Coogee told me his C.O.at Victoria Barracks first rejected Owens prototype as a ” Gangsters Gun”, but when Crete was taken by German Paratroopers with Machine Pistols he showed visiting Manager for Wollongong Steel Works Owens prototype in .32 acp. ( it was still in a Hessian Sack in a corner of the Govt garage ).According to Captain Rowe (Retired)they put a few clips through it ,made some slight modifications and placed said machine carbine into immediate production which is in conflict with official story.

It does more than contradict the official story, it contradicts official documents and one of the men who designed the Owen.

Post WWII we were taught to fire 2-3 shot bursts with the Owen, doing this from the hip on the run through a simulated combat situation was great fun. It was instinctive to aim from the hip too, with a bit of practice it was quite easy to fire just one shot on auto. Gun’s main feature was it was reliable as a rock, mud and crap no problems, it just kept working. Great gun.

Jacko – a relative of mine, used the Owen and the Bren gun throughout the islands in WW2. I thought he would have loved the Bren, but his comment was “the beaten zone of the Bren was too tight – with the Owen we could just aim at the chest and pull the trigger – he loved it and it sounded like the Owen got him and his mates out of trouble quite a bit.

Thoses of us who have carried and used the Owen know what a weapon it was.As a submachine gun none better! As one who carried it for a time in South Vietnam with C Coy 1 RAR 65-66 the only complaint was that the 9mm ammunition we used was WW2 stock. In WW2 9mm ammunition was meant to be used before 3 months old,then it would deteriorate due to the tropical climate,9mm ammunition in WW2 was very powerful and 9mm ammunition marked “9mm for submachine guns only” was loaded up to give that extra punch.In South Vietnam thoses who carried the Önion gun were up against it from the start not because of the OMC but 1945 ammunition,anyway a new toy had arrived called the M15 Armalite,new yes better than the OMC at close quarters No! Stan Hanuszewicz

Used one in Vietnam. Loved it. Only ever got one bad lot of ammo – sold it to the Yanks, it worked OK in Browning pistol. Never could come to grips with the F1, and the M16, well, it would be useful as a stake for tomato vines, I suppose. Self cleaning! What a load of crap. never went anywhere with an M16 without a toothbrush tied to the carrying handle to clean the bolthead & chamber. It has improved since I’m told. Did ‘liberate’ some German 9mm ammo from a dump, and it worked OK, but some of it had explosive projectiles, and the boss had a fit, and had it destroyed. Spoilsport

I was in the old National Service in the 1950’s and used the Owen. I for one was not bothered by the weight but impressed with the weapon.

Right or wrong, I do not know but I was told by senior N.C.O’s instructors that served in ww2, that ammo was not a real issue because you could (according to them) use both German and Japanese 9mm ammo if you ran out. Not only that but you could use (I think) 38 cal bullets if no 9mm available but the slightly larger 38 stuff did muck up the barrels if used too much.

Used both the owen and Thompson but found the Owen better to control and felt lighter.Both excellent close quarter weapons.

Thank you for this informative article. I read somewhere

that changes were made to the owen smg design to stymy

its chances during testing by the british. Is this true?

I wonder just how many aussie lives would have been saved had this weapon seen widespread use in the jungle

theatres of papua and borneo! Was it used there?

My Grandad mentioned using it in Borneo in raids, also said 9mm didn’t penetrate the jungle well enough to keep heads down and the .303 was the choice for that.

This OMC while effective in close quarters did have a number of problems. I used a 9MM version while in the CMF. In auto mode if you fired mor than 3 shots you were shooting down birds. The kick was so bad you could not keep the nose down no mater how hard the pressure applied to the forard grip. The danger of this weppon is that it loads and fires all in one action as long as the trigged is held to fire. One training night we were practising loading and unloading OMG Magazine. While officially there was no such thing as training 9MM amunition, the cases were painted with a red band and projectiles fitted. The correct method of unloading is to use the projectile nose to push a round forward and out of the magazine. At the end of the evening it was decided to unload all magazines quickly by using the action of the OMC while those present grabbed the ejected rounds. It later was found there was one live round with the practice rounds that on ejection fired and hit a person in the stomick at a range of 1 foot from the barrel tip. An extesive investigation was conducted by the ADF but I am not aware of the results.

The Diggers Darling in WW2. BEAUTIFUL To handle and shoot.

Ηellߋ! I simply wouⅼd like to give you a huge thumbs up for the great info you

have here on his post. Ι am coming baacқ to yoսr website for more soon.

Great article! The Armourers poster, did you get that from Gunboards or Milsurps forums….

My old man used Owen guns in Malaya and viet nam , asked about the sights ( he was a jungle warfare instructor) first reply in his usual snide manner was , “never knew they had them and anyone who bothered to use them is dead , they were used by first scouts to suppress and second scout would advance and target with rifle if necessary. Unlikely as they were very effective to 40 foot off the hip, all our soldiers were well trained in firing off the hip , you don’t get much chance in the jungle. We were much better at it than the Brit’s or yanks , because of the training and our history in that type of warfare. We spent a lot of time training them “Those boys were good bloody good very proud of them “ “used to walk along a concrete wall at Victoria Barracks behind them and throw a beer can over their heads bounce it off the wall if they didn’t hit it go to back of the line and start agian ( used a semiauto .22 ) “ got in deep shit for the damage to the wall “ “ when shits were trumps best weapon to have “