In the years prior to World War I, the US Army Ordnance Department was already investigating the possibility of adopting a self-loading service rifle, even as the 1903 Springfield rifle was being adopted. In 1904 and again in 1909, the department published the testing procedure that would be undertaken for semiauto rifles submitted for consideration. Between 1910 and 1914, seven different models were tested (not counting developments from within Springfield Armory and semiauto conversions of the 1903). These seven were the Schouboe (aka Madsen), Dreyse, Benét-Mercie, Kjellman, Bang, a design from the Rock Island Arsenal, and one from the Standard Arms Company.

The rifle submitted by Standard Arms is also known as the Smith-Condit, after its designer (Morris Smith) and the secretary of Standard Arms (W.D. Condit). The company had high hopes for its design, and had incorportated in 1907 with a million dollars of capital and purchased a factory where it planned to employ 150 workers and produce 50 rifles per day (source: The Iron Age magazine, May 23, 1907). These hopes turned rather sour when the military testing was done, though. Ultimately the design was revised into the Model G and a few thousand were sold commercially. Remaining parts were used in the Model M, which was essentially the same gun but with the self-loading mechanism replaced by a slide action.

But, back to the military design – the commercial Standard Arms rifles will have an article of their own later. The military rifle was tested twice in 1910, and rejected both times, primarily because it was deemed to fragile for military service (which would seem reasonable, considering the problems that plagued the commercial guns).

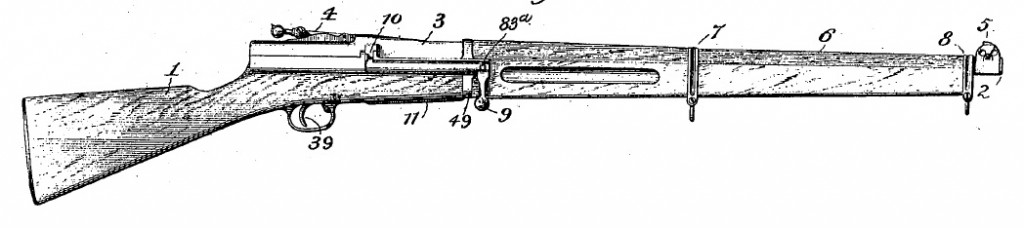

Mechanically, it was a gas-operated design with a gas port a few inches shy of the muzzle and a piston running underneath the barrel. The piston split into two wings to avoid the 5-round integral magazine, and operated a tilting block which would pivot up to lock into the top of the receiver. Upon firing, the piston would force the locking block down, and then the bolt was freed to travel rearward, extracting and ejecting the spent shell and loading a new one. It was also equipped with a cutoff on the gas system, allowing it to be run as a straight-pull bolt action instead, which was a feature desired by the military. A fairly conventional by today’s standards, but a difficult design to manufacture in 1910.

There seems to be some question as to the caliber of the test guns, as different sources suggest three different calibers (and it is certainly possible that the caliber changed when the gun was re-submitted to military trials). One example sold by Cowan’s is described as being in .30-06 (nd has a military-style stock and front sight). Another one sold by Rock Island is described as being in a proprietary .30/40 Short, and a third held in the Springfield Armory collection is listed as being in 7mm. Of those three, only the Rock Island one has detailed photos:

In addition to its fragility, the rifle was found by the Ordnance Department to have too complex of a disassembly procedure, too low a rate of fire, and to not be strong enough to handle full-power military ammunition (as if any one of those wasn’t enough). Needless to say, it never went any farther with the military.

Morris Smith’s patent #817,198 (the rights to which were purchased by Standard Arms) is the basis for this design, but he had several other firearms patents from around the same time. You can see those here:

US Patent 784,966

US Patent 814,242

US Patent 817,197

US Patent 818,920

Always interesting to see the steps man took to get what we have today.

This is actually quite straight-forward design in its essence, albeit bit cumbersome in the conduct. Swing link lock up – that’s what it is, would have been more practical if directed down instead, similar in the way the Vz.58 works.

Just a short glance reveals potential problem with elements ingress on top of receiver. other than that – thumbs up!

One can definitely see the Model G lineage in the rifle in the photos. The receiver profiles are very similar, and it didn’t take much alteration to adopt the slide-action cocking mechanism. When looking at some of the rifles being tested, the flaws are obvious, but when one considers the variety of self-loaders being tested at the turn of the century, I suspect that even a good rifle would not have been “good enough” for the traditionalists in the Ordnance Dept.

I like the design. The locking block and internal parts look like they would be relatively easy to manufacture with 1910-era machinery… everything except the receiver, which looks like it would be a major hassle.

The rear sight looks delicate, and I’m not too fond of the top ejection, though from the patent it doesn’t look like there was much choice.

Yes, it makes sense what you say about the ejection part. Not bad.

Just to point out a historical detail, the article says “incorportated in 1907 with a million dollars of capital”. I haven’t read the original source, but they may not actually have had a million dollars in actual shareholder capital. That may have been their *authorized* capital.

When a company incorporated, their papers would state an amount of capital that the directors would be authorized by the shareholders to raise. In this case the one million dollars likely referred to the maximum amount in shares that could be sold without getting further authorization from the shareholders.

It was normal with a new company to set some arbitrarily large limit when the new company was first incorporated. Many companies never at any time have reached a capitalization anywhere near that original number. Those that did were exceptionally successful.

I’m just bringing this point up just to point out that the authorized capital (if that is what the number represents) doesn’t tell us how much financial backing Standard Arms actually had.

That’s an interesting point I wasn’t aware of, MG. The original source I used is here, and it isn’t really specific as to the money being raised or authorized. However, the financial backing came from the DuPont family, so there was certainly potential for a lot of actual cash.

Ian,

Patent Number 814,212 is incorrect. The correct number is 814,242.

Max

Fixed.

Btw Ian, the pictures you’ve used are of 2nd pattern model, the first pattern (almost identical to the rifle depicted in US814242) can be found here – http://www.rockislandauction.com/viewitem/aid/61/lid/307. Seemingly 2nd pattern used the same butt stock, barrel and front sight as the 1st pattern but had a completely different receiver. The 3rd pattern used a slightly modified receiver of the 2nd pattern, and also a modified early Springfield M1903’s (aka rod bayonet) front sight. Additionaly I found an article from 1910, it can be viewed here – http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101043278793;view=1up;seq=20 (pages 151-155). Cheers and keep up the good work.

Thanks!