Concept

The idea of converting bolt action rifles into semiautomatic or fully automatic designs is not a unique one. It used to come up fairly regularly – most national armies investigated the concept at one time or another in the past 100 or 150 years. Most of them were experimental (like this Dutch Mannlicher conversion or the Huot conversion of the Ross rifle), and the only one to really achieve significant production was the Pedersen Device, which was a blowback pistol caliber conversion rather than a true rifle caliber conversion. New Zealand’s Charlton Automatic Rifle is the most successful of the true rifle conversions, as well as one of the most ungainly looking. Well, despite looking a bit Italian, it was really a triumph of engineering under adversity.

Early in the Pacific theater of World War II, New Zealand (and Australia too, but they are a story for another day) was facing a very serious perceived threat of Japanese ground invasion and was woefully underarmed, particularly in the realm of support weapons. The British crown was unable to provide much help, being in the middle of a desperate fight with Germany and having lost an immense amount of material in the Dunkirk evacuation. Material was limited, production capacity was limited, and machine guns were in very short supply. Enter Philip Charlton (1901-1978) and Maurice Field.

Charlton and Field were both shooting and gun collecting enthusiasts; Charlton an inquisitive engineer and Field with the financial means to back an entrepreneurial endeavor. The two formed a freidnship in the late 1930s, and continued to shoot together into the early 1940s. Seeing the threat of invasion and the sorry state of New Zealand’s armories, Charlton suggested to Field that he was considering adapting his Winchester Model 1910 self-loading rifle (chambered for .401 WSL) to fire automatically for military use. Field convinced him that ammunition availability would make that a non-starter for the military, and instead the pair decided t convert a Lee-Metford bolt action rifle into a light machine gun. Such a weapon would use the standard .303 Army cartridge, and the New Zealand Home Guard had plenty of old Lee Metford and Long Lee rifles dating from 1889 to 1903 that could be subjected to such a conversion.

Design

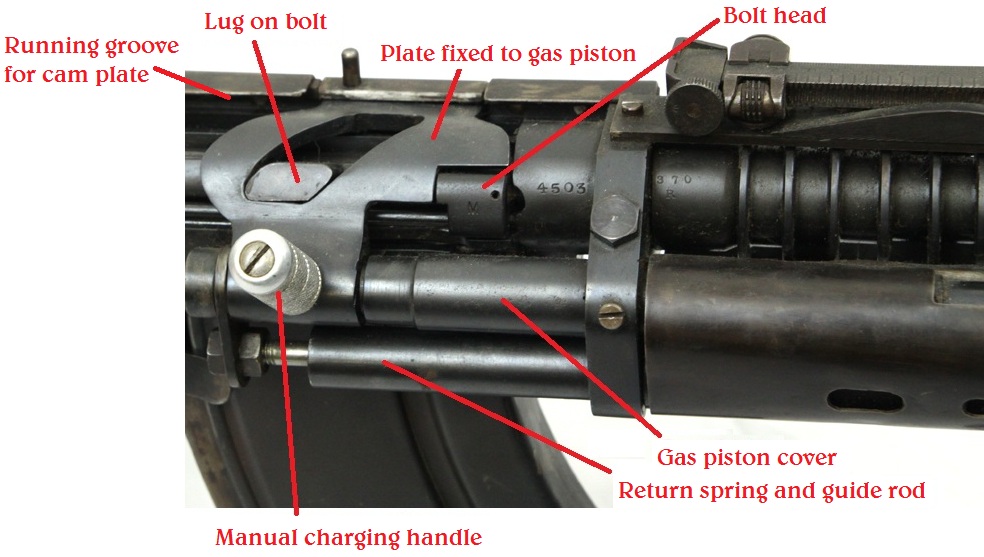

The idea behind the Charlton and other conversions like it is to add a mechanism to a bolt-action rifle by which the energy from firing is used instead of a human motion to operate the bolt. This was done by drilling a hole in the side of the barrel up near the muzzle and mounting a gas piston to the right side of the gun. A second tube right below the gas piston carried a recoil spring and guide rod, to return the piston forward after each shot.In addition, elements like two vertical pistol grips were added to allow more comfortable use from a bipod or from the hip, and cooling fins added to the barrel to aid its cooling (the original bolt-action rifle barrels are not intended for sustained fire).

The most difficult single part of the conversion is translating linear forward and backward motion of the gas piston into the rotate-up/pull-back/push-forward/rotate-down motion needed to operate a turnbolt rifle. Charlton (and most of the other designs along these lines) used a scroll cam to do this – a machined part with a curving slot for the bolt handle stub to ride in:

As the piston begins to move backward upon firing, the bolt is locked in place and the cam plate forces it to rotate. Once it’s fully open and can rotate no further, the continuing rearward motion of the piston pulls the bolt backwards and extracts the fired case. When it has traveled all the way back and gas pressure is exhausted, the recoil spring takes over and drives the cam plate forward. The bolt follows in the exact reverse of its opening motion, first being pulled forward and then rotating to lock with a new cartridge in the chamber. In order to keep the cam plate stable, it runs in a groove in a metal plate attached to the left side of the receiver, as well as being fixed to the end of the gas piston.

Charlton got to work on the project and built a functional prototype in the spring of 1941. The initial model had problems malfunctioning that were eventually tied to a weak ejector. A local radio engineer named Guy Milne built a stroboscope (an early type of high speed camera) timed to match the cyclic rate of the gun and enabled Charlton to see the cause of the malfunctions and correct it. In addition, the simple trigger mechanism Charlton had designed worked great in full auto, but would not reliably fire semiautomatically (a reflection of the counterintuitive truth that a semiauto firing mechanism is more complex than a full-auto one). Finally, the rifle was limited in a practical manner by its 10-round magazine and 700-800 rpm rate of fire.

At this point, Charlton decided that the Army would be primarily interested in his design as a machine gun, and approached the government along with his local M.P. In June of 1941 they put on a very successful demonstration at the Trentham Army Camp, with Maurice Field firing the weapon and Philip Charlton exercising his skills as a salesman. The demonstration was received enthusiastically, and resulted in Field and Charlton being provided 10,000 rounds of .303 ammunition with which to further refine the gun. Five months later, in November 1941, the pair returned to Trentham with the prototype (which now had well in excess of 10,000 rounds fired through it) and put on another very successful demonstration. They came away with a contract to convert 1500 Lee Metford and Long Lee rifles from the Home Guard armories.

Manufacture

In many ways, building the working prototype and getting military approval of it was the easy part for Charlton and Field. Now that they had their formal contract in hand, they had to figure out how to make the Charlton conversion into an efficient production job. They had to do this in New Zealand’s riskiest time of the war, with very limited material supplies and a supply of 50-year-old rifles that had been “rode hard and put away wet,” so to speak.

Charlton began by bringing into the project his friend Syd Morrison, who ran the Morrison Motor Mower company – whose business was struggling because of the gasoline rationing at the time. Morrison had the machine tools to do much of the work making parts for the Charlton, and it was in his shop that Charlton had done much of the work building his original gun. Morrison (apparently a savvy businessman who did not want to be bogged down with time-intensive details) began to make parts in bulk, delivering them to Charlton for hand fitting and assembly. In fact, at this point there were no technical drawings of the gun or its parts, as neither Charlton nor Morrison considered them necessary.

Since it was now operating on an Army contract, the hole project was officially under the control of the Munitions Department, and was administered by one Squadron Leader John Carter or the NZ air force and his assistant Gordon Connor, the very competent Engineer for the NZ Railway Department. The contract specified that the 1500 converted rifles were to be finished within 6 months, and Connor could see that this date was hopelessly out of reach at the rate production was going. He arranged for several of the parts to be outsourced to a number of other manufacturing shops, including barrel fins and trigger mechanism side plates to Precision Engineering Ltd of Wellington, recoil springs to N.W. Thomas & Co Ltd of Wellington, and even gas pistons to the machine shop class at the Hastings Boy’s High School (although only about 30 were made before Morrison took over production of that part).

Charlton had run an auto body shop before the war, and like Morrison’s business it was in deep trouble because of gas rationing. By this time Charlton only had one employee left, a young man named Horace Timms. On January 2nd, 1942, Charlton and Timms began setting up Charlton’s auto body building as a rifle factory. Charlton brought in a friend named Stan Doherty, who was also an engineer in the automotive industry, and the three of them set up equipment for metal heat treating, bluing, assembly benches, and a 25m test firing tunnel in the shop. At this point rifles began to arrive from the Army, and staff were hired to clean and inspect them in preparation for conversion.

Another engineer (and First World War veteran) by the name of Stan Marshall was brought in as well, and shortly thereafter Charlton was called away to Australia to discuss a contract for converting guns for the Australian government. In his absence, it was left to Marshall and Doherty (under the administration of Gordon Connor from the Munitions Department) to get serial production under way. These men realized that producing parts from samples without drawings (as Charlton and Morrison had arranged) was very inefficient, and that some of the manufacturing methods used on the original gun would not scale well on the factory floor. Marshall and Doherty proceeded to strip down the prototype and devise the best way to mass produce it, making a few tweaks to parts along the way. They built a second gun using the best production methods they could devise (while the Army’s donor guns were busy being disassembled and cleaned), and were able to significantly decrease the fabrication time by designing a number of specialized jigs and fixtures. In fact, by the time the final guns were being made, nearly all the need for hand fitting had been removed, and production was quite efficient. The production of the 1500 contracted guns ultimately took two years, but they were all finished and each gun individually inspected and approved by the Army.

The biggest problem encountered along the way was sourcing magazines for the guns. Charlton had modified a Bren gun magazine for use in his original prototype, to replace the standard 10-round Lee magazine. He planned to modify magazines the same way for all the production guns, but Gordon Connor decided that it would be more efficient to subcontract the magazines to an Australian company already making Bren magazines, as those folks could make a batch of 1500 modified mags (apparently the Charlton rifles would be supplied with only one magazine per gun) in just a few weeks. However, the magazine production took much long than anticipated and when they finally arrived, the didn’t fit the guns. Each new magazine had to be milled again in New Zealand to fir the Charltons, and ultimately only the last 50 guns in the contract were actually delivered to the Army with proper 30-round magazines. The remainder of the magazines were sent to the government depots about 3 weeks after the final rifle delivery.

The Australian Connection

In the middle of the process of setting up the manufacturing facilities in Hastings, Charlton was asked to make a trip to Australian to negotiate conversion of rifles for the Australian government. His trip was expected to take 10 days, and ended up stretching to 4 months (during which time Doherty and Marshall got the assembly line conversion process in motion). An agreement was reached to have 10,000 more rifle converted to Charlton’s mechanism, with the work done by the Electrolux company and Charlton himself receiving a small royalty for each gun. Electolux made a small number of prototypes, and while their mechanism is basically the same as Charlton’s original the guns looks quite different.

Distribution

The Charlton Automatic Rifle was never intended to be issued to front-line New Zealand troops, but instead was to be kept in reserve for the Home Guard in case of invasion. Once formally accepted by the Army, the Charltons were crated up and distributed to three strategic depots – Narrow Neck (Auckland), Ngaruawahia (near Hamilton), and Burnham (near Christchurch). They were never needed, and after the war they were moved to a storage building at the Palmerston Grounds – where a fire sadly destroyed them all. A very small number remain in existence in museums in New Zealand, Australia, and England.

Photos

Courtesy of the National Firearms Centre in England (aka the Pattern Room), we have more photos of an original Charlton (click here to download the photos as a high-res zip archive):

In addition, we have a set of photos of a gorgeous reproduction Charlton currently available for sale at Gun City, in Christchurch New Zealand (click here for that set as a zip archive):

Manuals

We have a copy of an original Charlton manual available for download as a PDF:

The Australian Army Infantry Museum at Singleton NSW has two live firing examples in its collection, one converted to LMG (see link) and the other as a semi auto rifle. The Australian Army Museum at Bandiana also has the LMG in its collection but this was demiled some time ago

http://infantrymuseum.com.au/thompson-gallery/#!prettyPhoto%5Bgallery%5D/14/

Demilling these should be a crime

Your link labelled “like this [Dutch Mannlicher conversion]” in the first paragraph links to a 404 page (https://www.forgottenweapons.com/early-semiauto-rifles/dutch-semiauto-conversion/)

In the third paragraph, you misspelt “friendship”

(The two formed a [freidnship] in the late 1930s…)

14th paragraph, “fit”

(Each new magazine had to be milled again in New Zealand to [fir] the Charltons…)

15th paragraph, “Australia”

(Charlton was asked to make a trip to [Australian] to…)

3rd paragraph, “to”

(instead the pair decided [t] convert a Lee-Metford)

Thank you for all your work ,for us ,

Speaking as a welder that extra operating cam lug put on the bolt is a recipe for disaster, causing distortion of the bolt body, and fracture at the weld zone, they only had crude welding methods then which required a lot of heat input. The straw colour of the bolt says to me they annealed and re hardened the whole bolt, but that extra lug will come off at some point if it gets a battering. The guide rib on the LE bolt is not under load at the front so they could have dovetailed or screwed the new lug on. A new bolt head with a lug on it would have been a better option.

They all passed extensive test and bolt breakage was never a problem.

Ignore the last sentence above.

Fascinating. I saw a Chauchat out of the corner of my eye. Nice Article/Video

Fascinating item. Very interesting to compare to other conversion kits like the M1915 Howell and Pederson Device. Ingenuity at its finest. Cheers, my friend.

“the hole project” or “the whole project”?

Thanks for a cool article!

I really like the idea of tying the site and YouTube content together. Hopefully it drives more regular traffic from YouTube to a platform under your own control.

I appreciate the link too! I’m here!

Excellent Gentlemen, thanks for keeping this most interesting weapon from disappearing from view.

Too bad the manual is so faint – still don’t know what is with the chain etc. at back end of piston etc. Ian your M.E. blessing is slipping here, your comment is invited. I be

mostly a ‘lurker’ (non $ contributing so far) – Phoenix AZ – do hope to snail mail you a couple pages I’ve copied – After Tax season ;-( stay Well!

D. Moore

Kiwi collector here. Is still a couple of these, (and a few reproductions) in private collections around the country, mercifully, not all destroyed in the confiscation.

Another interesting note, been lately uncovered from looking at the salvage documents after the fire, is 30 guns unaccounted for, (not found destroyed) from the fire and is a researcher who is trying to track down, what happened to those 30 missing Charltons. So there maybe still a couple around somewhere.