One of the relatively few successful competitors to the Maxim in the early days of the heavy machine gun was the Col Model 1895 (aka, the Potato Digger). When it was adopted by the US in 1895, one of the elements in its favor was its light weight – just 35 pounds (not including mount). The Colt was an air cooled gun, which is a large part of how it was able to be so much lighter than the Maxim. This, predictably, did not sit well with Hiram Maxim, and he proceeded to make an extra-light version of the Maxim.

This version weighed in at just 27.5 pounds (12.5kg) of gun, and 44.5 pounds (20.2kg) complete with its tripod mount. That was quite impressively light, and it impressed the US trials board. However, this weight reduction was accomplished in large part be eliminating the cooling water and reducing the diameter of the barrel jacket (a jacket was still required to provide a bearing surface at the end of the barrel for the recoil action). Four cooling holes were cut in the bottom of the jacket, but these were wildly insufficient to allow proper cooling of the barrel, and as a result he gun overheated quickly. Maxim himself suggested that firing more than 400 rounds continuously would be unsafe. Why a much more heavily perforated jacket was not tried (as would be used 20 years later for the aircraft Maxims used by several nations) is not clear – it may simply have not been an idea that was considered in time.

A quick-change barrel would have helped to ameliorate the gun’s cooling liability, but this was not really possible with the general Maxim action. As a result, the Extra-Light Maxim failed to attract any significant sales, with handfuls of examples being sold here and there for evaluation and little more (for example, the company’s attempt to market a two-man, two-gun tricycle failed to gain any buyers). It did serve to keep Maxim’s name in the minds of the US military, though, and this would finally pay dividends when the US adopted a more standard Maxim gun in 1904.

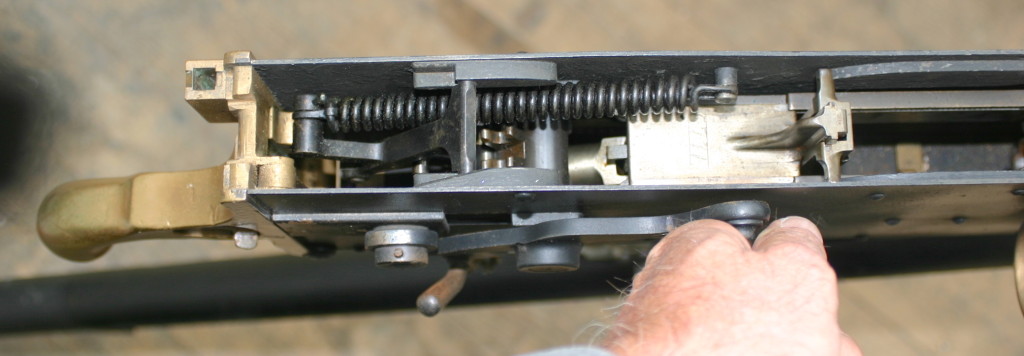

Mechanically, the Extra Light was not the dead end that its commercial failure would suggest. It incorporated several new ideas, most notably a fully internal mainspring. Rather than having the mainspring (fusee) attached to the outside of the receiver, in this model it was internal. This saved space and weight (no mainspring cover need, for example), but at the cost of not being readily adjustable. That adjustability was important to the Maxim’s reliability, and the internal spring would not see further use. The other new feature of the Extra Light would become standard for all Maxim guns, however.

This second new feature was the use of an elegantly curved crank handle in conjunction with a roller cam. This made the transition from rearward recoiling motion to rotational unlocking motion much smoother than in the earlier models (in which two flat surfaces slammed together) and reduced the potential for parts breakage. This improvement (along with 12 others) was patented by Maxim in 1894 British patent #16,260.

Very few of these guns exist today, and I has the opportunity to take some photographs of one example complete with its tripod:

Thank you Ian for this interesting report on the ever evolving Maxims pre-WWI.

What caught my interest was the ample use of brass and that got me to questioning.

Why was brass so abundant on the Maxims back before WWI?

Was it for simply aesthetics and was it then cheaper than steel or was there a practical reason for its use– cooler to the touch than steel?

Anyway, all that brass attracts me (as does bronze) and marks these guns as being special, beautiful, and within the classical epoch.

Regards

Pat

If I am not mistaken brass/bronze is more mild than steel, so it is easier to process (can be machined faster) and also according to:

http://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/melting-temperature-metals-d_860.html

brass has lower melting point (around 1000°, vary depending on variant) than steel (around 1500°) so less energy is needed if you want to cast it

Brass and bronze are indeed much easier to work.

Easy to work means easy to repair. For ease of maintenance and durability, the Vickers Wellington had a geodesic airframe which was cheaper to fix than that of a semi monocoque configuration… Or did I mess up again?

That brass was easier to machine is especially relevant for any arms made before 1900. Around 1900 high speed steel was invented and that revolutionized the speed at which lathe and milling cutters could machine steel.

1900 was also the year when 3 phase electrical generation and induction motors started to be used. Prior to that factories tended to have one big steam engine or one big electric motor for power and that power was transmitted to individual machines by complex sets of belts and overhead shafts. Reliable, less expensive, and powerful motors meant easier machining of steel, especially when combined with high speed steel cutters.

Because of its easier processing qualities, bronze was also used for making barrels of field artillery pieces up to WW1. Especially Austro-Hungarian artillery makers (Škoda and others) used bronze due to insufficient capacity of high enough quality steel production. The 8cm (76.5mm in fact) field gun was the most common Austrian artillery piece and had a bronze barrel. Some of these saw some limited service even in WW2 in Italian hands (Italy received a lion’s share of former Austro-Hungarian artillery pieces as war reparations after WW1):

http://www.landships.info/landships/artillery_articles.html?load=/landships/artillery_articles/8cm_Feldkanone_M5.html

One wonders if the reciprocation could be used to power an specialized air-pump?

Possibly, but you only have so much recoil energy, and it has to reliably cycle the gun more than anything else.

Trying to move a lot of air is going to be problematic, though you could probably get some effect going.

(Other things you might do are make a finned barrel, but the machining cost would be exorbitant even today.)

Google up an Airpot or Ace shock absorber. Heat could be a problem.

The North West Mounted Police bought a light weight Maxim No 5627 in 1897. It was positioned on the Yukon/Alaska border crossing at White Pass during the gold rush of 1898.

There’s definitely something aesthetically pleasing about the Maxims, besides the blending of brass and steel. Maybe it’s just the ingenuity in the design work, the epitome of 19th century mechanical engineering. They’re really works of art.

Ian, thanks for sharing this!

Any idea why it’s in .303 if it was for a US trail?

That, and are you at the Royal Armouries?

This particular one isn’t one of the US trials guns; I believe those were in .30-40 caliber. And no, this gun isn’t at the Royal Armouries.

Maxim was working in the UK and trying to get more War Department contracts at the time.

IIRC the black powder .303 wouldn’t run the existing Maxims in British service (originally designed for .577/450), so they continued using .577/450 Maxims alongside the Lee-Metford for a while.

I find it interesting that this lightweight one is indeed chambered for black powder .303 (a lot of the later ones are marked “cordite”).

Perhaps putting these two things together, part of the calibre choice was to prove to the WD that Maxim could make an MG run on .303 Mk.I?

In the same vein, Theodore Bergmann and his team came up with the Bergmann MG15nA, a lightened version of the Bergmann 1910 water-cooled MG ( which was in the same class as the Maxim MG08 and Vickers 0.303″ MMG ). The MG15nA utilized an air-cooled barrel with a fully-ventilated barrel jacket that was generously slotted throughout its length, and which provided ample cooling. It was a pretty impressive gun for its time, having a user-friendly pistol grip, abbreviated buttstock / buttpad assembly mounted directly to the rear of the receiver, and even a carrying handle. Including its lightweight tripod, the whole gun weighed only 35 lbs, and it had a cyclic rate of fire of 550 rds./min. Belted ammunition was contained in a drum which fed from the right side of the receiver.

By all accounts, the MG15nA was very popular among front-line troops, being light and portable yet retaining the firepower and reliability of its 1910 predecessor, but not enough could be produced to satisfy general demand.

The Bergmann tends to be unfortunately forgotten simply by who they were typically issued to. While the Bergmann was available much earlier (in a.A vs. n.A configuration primarily), both the Bergmann LMGs were primarily issued in the Italian and Asian/Mesopotamian theaters of WWI where mobility was a key factor in engagements. However despite this a number of Bergmann guns (or “Bergmann-Gewehre”, as Balck’s Entwicklung der Taktik im Weltkrieg refers to them) were issued as stopgap on the Western Front in 1916 alongside captured Lewis guns until troops could be trained and supplied with MG-08/15s in very late 1916 and early 1917.

I’ve always wondered if the NFA applies to these, since they are pre-1898.

Yes, as the 1898 bit comes from the GCA, not the NFA. (Although amusingly you don’t have to fill out a 4473 to purchase one…)

It does – they are not “firearms” but they are “machine guns” in the view of the law.

If I am not mistaken brass/bronze is more mild than steel, so it is easier to process (can be machined faster) and also Brass has lower melting point (around 1000°, vary depending on variant) than steel (around 1500°) so less energy is needed if you want to cast it.

Brass and bronze are indeed much easier to work.

That brass was easier to machine is especially relevant for any arms made before 1900. Around 1900 high speed steel was invented and that revolutionized the speed at which lathe and milling cutters could machine steel.

Because of its easier processing qualities, bronze was also used for making barrels of field artillery pieces up to WW1. Especially Austro-Hungarian artillery makers (Škoda and others) used bronze due to insufficient capacity of high enough quality steel production. The 8cm (76.5mm in fact) field gun was the most common Austrian artillery piece and had a bronze barrel. Some of these saw some limited service even in WW2 in Italian hands (Italy received a lion’s share of former Austro-Hungarian artillery pieces as war reparations after WW1):

So, given the above—why, after WWI, we see little or no brass and bronze used in firearms, excluding Italian reproductions of American frontier guns??

Apart from the greater availability of more advanced metallurgy with regard to steel alloys at a viable price point combined with advances in machining and stamping technology, the cost of high copper bronze and brass has soared due to demands from other industries, along with an attendant market price increase. The castings and billets from which brass or bronze components would be machined nowadays would be prohibitively expensive while not providing the level of material performance ( heat resistance, compressibility, damage resistance, etc. ) that modern gunsteels provide.

Don’t you think it would be appropriate for you to give the credit to the guy who took all of these photos?

Well, I’m the one who took the photos, so…

So, “I.M. photographer” would be a suitable, subtle, citation.