The Mars pistol was a development of the turn of the century that would really be more at home in a Jules Verne novel (I would suggest the title “One Thousand Footpounds in a Handgun”) than in the real world. It was a massive handgun, ridiculously powerful, and marvelously complex. It lasted only for a short time, with the first production prototype made by Webley in 1898 and production ceasing by 1907.

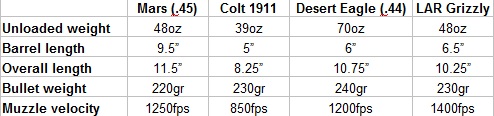

To put the gun’s physical size in context, consider the numerical data. The Mars is 25% heavier and 30% larger than the Colt 1911, and fires a very similar projectile at 50% higher velocity. Its closest comparison today is the LAR Grizzly in .45 Winchester Magnum.

Operation

The Mars is one of the few long-recoil action firearms designed and built, and this choice of action contributes to its complexity. Hugh Gabbett-Fairfax, its inventor, was dedicated to the long-recoil system because it offered a high margin of safety for his very powerful cartridge. The idea of a long recoil system is that the bolt and barrel remain locked together as the whole system recoils backwards, and only unlock when fully rearward (as opposed to short recoil, where the two parts unlock while the bolt is still moving backwards). The long locked time means that the bullet will have left the barrel and pressure will have dropped a great deal before the system opens, thus protecting the shooter.

It is worth comparing the Mars to the only reasonably successful long recoil pistol, which was the Frommer 1912. In the Frommer, bolt and barrel travel back together, and the bolt is held at it rearward position while the barrel returns forwards. The empty case is ejected as the barrel pulls off it, and when the barrel is fully home is trips a release to allow the bolt to come forward, stripping a new cartridge from the magazine as it does so. The Mars prototypes initially functioned this way (including the use of a rotating bolt, with 4 lugs in the case of the Mars), but had reliability problems. The travel distance of the moving parts (the Frommer bolt and barrel travel about an inch, compared to 3-4 inches on the Mars) combined with the significant recoil of firing tended to bounce things around and led to feeding failures. The solution was twofold. First, the normal magazine was replaced by a cartridge elevator which would pull a round backwards out of the magazine during recoil and then lift is up into the path of the bolt. Secondly, the automatic bolt release was replaced by a mechanism which held the bolt open until the shooter released the trigger.

So,if one was to press the trigger and hold it back, the Mars would fire and lock open with a new cartridge lifted and ready for chambering, but the bolt would not be released to slam forward and lock until the trigger was released. This led to one of the perennial complaints about the gun in military trials; it had a very heavy trigger pull. In addition, this mechanism was spring loaded until late in the production run, and it was possible for the bolt to jump over the catch and follow the barrel home, which was responsible for many of the feeding problems encountered in testing. The mechanism was progressively improved, and by the final few guns made it was made wholly of positive mechanical cams and the problem was eliminated.

Production

The first Mars pistol was made by Webley & Scott, one of the foremost revolver manufacturers in England at the time. Automatic pistols from the mainland (Borchardt and Bergmann, among others) were showing popularity, and Webley wanted to get its foot in the door. They contracted to build prototypes of the first Mars design in 1898, but the collaboration would not last. By the time Gabbett-Fairfax filed his 1900 patent that became the design for the standard Mars pistol, he and Webley had gone separate ways. The reason is a bit unclear, but likely relates to Webley trying to change the design to make it more commercially feasible – something Gabbett-Fairfax would have done well to cooperate with. Webley was also working on the Webley-Fosbery automatic revolver at this time, but it and the Mars were seen as complementary products and not direct competitors (in an 1899 letter published in Arms & Explosives magazine, Gabbett-Fairfax described the Webley-Fosbery as “excellent”).

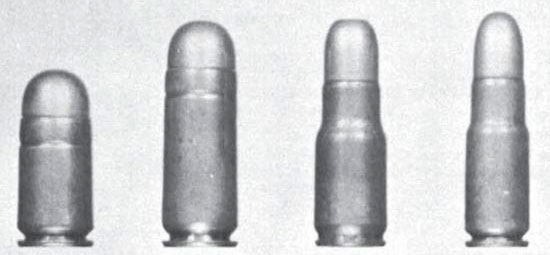

Serial production began in 1901 under Gabbett-Fairfax’s direction, and approximately 56 pistols were produced in several different calibers. The first Webley gun had been chambered for the ,360 Mars, and this cartridge continued to be used. It was a .36/9mm bottlenecked design with a 160-grain bullet fired at a very impressive 1640fps. An 8.5mm version was also produced for military trials in France (140 grain bullet at 1750fps), and a .45 caliber straight walled cartridge was also developed for British military trials (220 grain at 1250fps). A short .45 cartridge was also developed and saw very limited use, as a response to military complains over the gun’s excessive recoil.

The pistols made during this time were being revised on a continual basis, and no two are exactly alike. Parts interchangeability is very limited, even between guns with very close serial numbers. Changes included incremental modifications to the firing mechanism, magazine parts, markings, and details like the lightening hole in the frame just above and in front of the trigger guard.

By the end of 1903, it became clear that no military contracts were going to be won, and Gabbett-Fairfax (who had been financing the whole project with personal loans) was hopelessly bankrupt. His patents were taken over by a consortium of his creditors under the name of the Mars Automatic Pistol Syndicate in an effort to revive the gun and recoup their investments. In late 1905 Clement Brown (formerly Gabbett-Fairfax’s shop manager) filed a patent for several improvements to the design. The Syndicate subcontracted manufacture out to a number of local Birmingham gunsmiths and in conjunction with remaining stocks of parts they attempted to market the improved gun in 1906. Their efforts failed completely, and by 1907 the effort was given up and the next year the Syndicate was also bankrupt, and dissolved.

Commercial Sales

Despite production of probably around 80 pistols, it appears that none were ever sold commercially. Britain’s Proof Act of 1868 required all commercially sold guns to be proof tests by an independent house, and this regulation was strictly enforced. Gabbett-Fairfax’s works were located very near to the Birmingham Proof House, and yet none of the Mars pistols known to exist today have any proof marks. A few were very likely given as gifts, but it would be extremely unlikely that any sale could have taken place without the Proof Master making a big stink about it.

Military Trials

Gabbett-Fairfax’s hopes for the Mars pistol were centered entirely upon military contracts, and the military trials of his pistol reveal many of its strengths and flaws. Between 1901 and 1903, he took the Mars to no less than eight demonstrations and military trials, and was given more chances to prove his design than most inventors. In general, military examiners held the Mar’s accuracy in high regard, and there was no doubting its man-stopping capacity. The objections were to its complexity, weight, recoil, hard trigger pull (10 pounds, according to one trial report), tendency to eject cases directly back into the firer’s face, and failures to feed.

Some of the feeding failures were due to the afore-mentioned problems with the bolt catch malfunctioning, and with shooters releasing the trigger too early. Other problems were often encountered with ammunition, including underpowered loads, insufficient crimps leading to bullets telescoping into cases, and uneven rim thickness. Through the several years of testing with the different branches of the British military, Gabbett-Fairfax had plenty of opportunities to revise the pistol to satisfy the complaints made about it – which were pretty much the same in every test. He failed to do so, though, and one really can’t blame the military for not giving him enough chances.

The final conclusion of the War Office Small Arms Committee described the Mars as: “A very powerful pistol. Its accuracy, penetration, and no doubt its stopping power, are good. It is, however, complicated, in its present form, would be difficult to clean, and is heavy. A great deal of firing has been carried out with it. The mechanism did not always work well, and the recoil was complained of. Much difficulty was experienced in obtaining satisfactory ammunition, and this was no doubt often the cause of defective working of the mechanism.” Ultimately, the committee concluded that automatic pistols were simply not well enough developed to merit military use at the present time.

Pictures

This particular Mars pistol is chambered for 8.5mm, and was sent to France for military trials (download the gallery in high resolution)

Manuals

Patents

US Patent 684,055 (H. W. Gabbett-Fairfax, “Automatic Firearm”, October 15, 1900)

British Patent 25,656 (Clement Brown, “Improvements relating to the Breech Mechanism of Automatic Fire Arms”, December 9, 1905)

Bibliography

Sturgess, Dr. Geoffrey L. “The Gabbett-Fairfax Mars Pistols” Journal of the Historical Breechloading Small Arms Association, Volume 2, Number 8.

Stewart, James B. “The Magnificant Mars” GUNS Magazine, July 1974